Laura turned off the ignition on the rental car and got out. Ray emerged on his side, searching the front of the house with wonderment. I had no choice but to join them. I felt like a prisoner, suffering a temporal claustrophobia so pronounced it made my skin itch.

Ray's mother's house was situated on a narrow lot on a street occupied entirely by single-family dwellings. The house was a two-story red-brick structure, with a one-story red-brick extension jutting out in front. The two narrow front windows sat side by side, caged by burglar bars and capped with matching lintels. Three concrete steps led up to the door, which was set flush against the house and shaded by a small wooden roof cap. I could see a second entrance tucked around on the right side of the house down a short walk. The house next door was a fraternal twin, the only difference being the absence of the porch roof, which left its front door exposed to the elements.

Ray headed for the side entrance with Laura and me tagging along behind like baby ducklings. Between the two houses, the air seemed very chill. I crossed my arms to keep warm, shifting restlessly from foot to foot, eager to be indoors. Ray tapped on the door, which had ornamental burglar bars across the glass. Through the window I could see bright light pouring from a room on the left, but there was no sign of movement. Idly, he talked over his shoulder to me. "These are called 'shotgun' cottages, one room wide and four rooms deep so you could stand at the front door and fire a bullet all the way through." He pointed up toward the second story. "Hers is called a humpback because it's got a second bedroom above the kitchen. My great-grandfather built both these places back in 1880."

"Looks like it," Laura said.

He pointed a finger at her. "Hey, you watch it. I don't want you hurting Gramma's feelings."

"Oh, right. Like I'd really stand here and insult her house. Geez, Ray. Give me credit for some intelligence."

"What is it with you? You're such a fuckin' victim," he said.

Inside the house, another light came on. Laura bit back whatever tart response she'd formed to her father's chiding. The curtain was pushed aside and an elderly woman peered out. In the absence of dentures, her mouth had rolled inward in a state of collapse. She was short and heavyset, with a soft round face, her white hair pulled up tightly in a hard knot wound around with rubber bands. She squinted through wire-frame glasses, both lenses heavily magnified. "What you want?" she bellowed through the glass at us.

Ray raised his voice. "Ma, it's me. Ray."

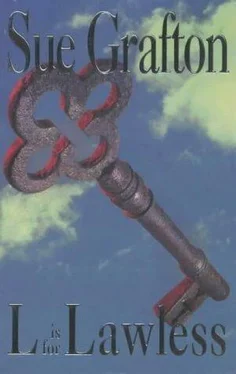

It took her a few seconds to process the information. Her confusion cleared and she put her gnarled hands up to her mouth. She began to work the locks – deadbolt, thumb lock, and burglar chain – ending in an old-fashioned skeleton key that took some maneuvering before it yielded. The door flew open and she flung herself into his arms. "Oh, Ray," she said tremulously. "Oh, my Ray."

Ray laughed, hugging her close while she made wordless mewing sounds of joy and relief. Though plump, she was probably half his size. She had on a white pinafore-style apron over a housedress that looked hand sewn: pink cotton with an imprint of white buttons in diagonal rows, the sleeves trimmed in pink rickrack. She pulled away from him, her glasses sitting crookedly on the bridge of her nose. Her gaze shifted to Laura, who stood behind him on the walk. It was clear she had trouble distinguishing faces in the cloudy world of impaired vision. "Who's this?" she said.

"It's me, Gramma. Laura. And this is Kinsey. She hitched a ride with us from Dallas. How are you?"

"Oh, my stars, Laura! Dear love. I can't believe it. This is wonderful. I'm so happy to see you. Looka here, what a mess I'm in. Didn't nobody tell me you were coming and now you've caught me in this old thing." Laura gave her a hug and kiss, holding herself sideways to conceal the solid bulge of her belly harness.

Ray's mother didn't seem to notice one way or the other. "Let me take a look at you." She put a hand on either side of Laura's face, searching earnestly. "I wish I could see you better, child, but I believe you favor your grandfather Rawson. God love your heart. How long has it been?" Tears trickled down her cheeks, and she finally pulled her apron up over her face to hide her embarrassment. She fanned herself then, shaking off her emotions. "What's the matter with me? Get on in here, all of you. Son, I'll never forgive you for not calling first. I'm a mess. House is a mess."

We trooped into the hallway, Laura first, then Ray, with me bringing up the rear. We paused while the old woman locked the doors again. I realized no one had ever mentioned her first name. To the right was the narrow stairway leading up to the second-floor bedroom, blanketed in darkness even at this time of day. To the left was the kitchen, which seemed to be the only room with lights on. Because the houses were so close to one another, little daylight crept into this section. There was only one kitchen window, on the far left-hand wall above a porcelain-and-cast-iron sink. A big oak table with four mismatched wooden chairs took up the center of the room, a bare bulb hanging over it. The bulb itself must have been 250 watts because the light it threw off was not only dazzling, but had elevated the room temperature a good twenty degrees.

The ancient stove was green enamel, trimmed in black, with four gas burners and a lift-up stove top. To the left of the door was an Eastlake cabinet with a retractable tin counter and a built-in flour bin and sifter. I could feel a wave of memory pushing at me. Somewhere I'd seen a room like this, maybe Grand's house in Lompoc when I was four. In my mind's eye, I could still picture the goods on the shelves: the Cut-Rite waxed paper box, the cylindrical dark blue Morton salt box with the girl under her umbrella ("When It Rains, It Pours"), Sanka coffee in a short orange can, Cream of Wheat, the tin of Hershey's cocoa. Mrs. Raw-son's larder was stocked with most of the same items, right down to the opaque mint-green glass jar with SUGAR printed across the front. The oversize matching screw-top salt and pepper shakers rested nearby.

Ray's mother was already busy clearing piles of newspapers from the kitchen chairs despite Ray's protests. "Now, Ma, come on. You don't have to do that. Give me that."

She smacked at his hand. "You quit. I can do this myself. If you'd told me you were coming, I'd have had the place picked up. Laura's going to think I don't know how to keep house."

He took a stack of papers from her and stuck them in a haphazard pile against the wall. Laura murmured something and excused herself, moving into the back room. I was hoping there was a bathroom close by that I could visit in due course. I pulled out a chair and sat down, doing some visual snooping while Ray and his mother tidied up.

From where I sat, I could see part of the dining room with its built-in china cupboards. The room was crammed with junk, furniture and cardboard boxes making passage difficult. I caught sight of an old brown wood radio, a Zenith with a round dial set into a round-shouldered console the size of a chest of drawers. I could see the round shape of the underlying speaker where the worn fabric was stretched over it. The wallpaper pattern was a marvel of swirling brown leaves.

The room beyond the dining room was probably the parlor with its two windows onto the street and a proper front door. The kitchen smelled like a combination of moth balls and strong coffee sitting on the stove too long. I heard the shriek of plumbing, the flush mechanism suggestive of a waterfall thundering from a great height. When Laura emerged from the back room sometime later, she'd shed her belly harness. She was probably uncomfortable with the idea of having to explain her "condition" if her grandmother took notice.

Читать дальше