“But how on earth did you know my real name?”

“A bit of deduction. When amateurs select an alias, they almost always keep the same initials. And they very frequently choose as a last name some form of modified first name. Jackson, Richards, Johnson. Or Peters. I guessed that your real name began with a P, and that it very likely had the same root as Peters. Something about your features suggested further that you might be of Armenian descent. I pulled out the phone book, turned to the P-e-t’s, and looked for an Armenian-sounding name with the initial E.”

“But that’s extraordinary.”

“The extraordinary is only the ordinary, Miss Petrosian, with the addition of a little extra. That’s not mine, by the way. A grade-school teacher of mine used to say that. Isabel Josephson was her name, and as far as I know it was not an alias.”

“I’m only a quarter Armenian. And I’m said to take after my mother’s side of the family.”

“I’d say there’s a distinct Armenian cast to your features. But perhaps I just had one of those psychic flashes people are subject to now and then. It hardly matters. You want that painting, don’t you?”

“Of course I want it.”

“Then write this down…”

“Mr. Danforth? My name is Rhodenbarr, Bernard Grimes Rhodenbarr. I apologize for the lateness of the call, but I think you’ll excuse the intrusion when you’ve heard what I have to say. I have a couple of things to tell you, sir, and a question or two to ask you, and an invitation to extend…”

Phone calls, phone calls, phone calls. By the time I was done my ears ached from taking their turns pressed against the receiver. If Gordon Onderdonk knew what I was doing with his message units, he’d turn over in his drawer.

When I was finished I made another cup of coffee and found a Milky Way bar in the freezer and a package of Ry-Krisp in a cupboard. It made a curious meal.

I ate it anyway, went back to the living room and killed a little time. It was late but not late enough. Finally it was late enough, and I let myself out of Onderdonk’s apartment, leaving the door unlocked. I walked all the way down to the fifth floor, smiling as I passed the sleeping Ms. DeGrasse on Fifteen, sighing as I passed the Applings on Eleven, shaking my head as I passed Leona Tremaine on Nine. I had a bad moment getting through the fire door lock on Five. I don’t know why. It was the same simple proposition as all the other fire door locks, but perhaps my fingers were stiff from dialing the telephone. I unlocked the door, and I crossed the hallway to another door, and after a careful look and listen I opened the door.

I was as quiet as a mouse. There were people asleep within and I didn’t want to wake them. And I had a great many things to do.

And, finally, they were all done. I slipped ever so quietly out of that fifth-floor apartment, locked the locks after me, and went up the stairs again to Sixteen.

You know, I think that was the worst part of it. Climbing stairs is hard work, and climbing ten flights of stairs (there was still, thank God, no thirteenth floor) was very hard work. The New York Road Runners Club has a race each year up eighty-six flights of stairs to the top of the Empire State Building, and some lean-limbed showoff wins it every time, and he’s welcome to it. Ten flights of stairs was bad enough.

I let myself into Onderdonk’s apartment once again, closed the door, locked it, and took a little time to catch my breath.

“Oh, great,” I said. “Everybody’s here.

“And indeed everybody was. Ray Kirschmann had shown up first, flanked by a trio of fresh-faced young lads in blue. He talked to someone downstairs, and a couple of building employees came up to the Onderdonk apartment and set up folding chairs to supplement the Louis Quinze pieces that were already on hand. Then the three uniformed cops stuck around, one upstairs, the others waiting in the lobby to escort people up as they arrived, while Ray went out to pick up some of the other folks on the list.

While all this was going on, I stayed in the back bedroom with a book and a thermos of coffee. I was reading Defoe’s The History of Colonel Jack, and the man lived seventy years without ever writing a dull sentence, but I had a little trouble keeping my mind on his narrative. Still, I bided my time. A man likes to make an entrance.

Which I ultimately did, saying, Oh, great. Everybody’s here. It was comforting the way every head turned at my words and every eye followed me as I skirted the semicircular grouping of chairs and dropped into the leather wing chair facing them. I scanned the little sea of faces-well, call it a lake of faces. They looked back at me, or at least most of them did. A few turned their eyes to gaze over the fireplace, and after a moment so did I.

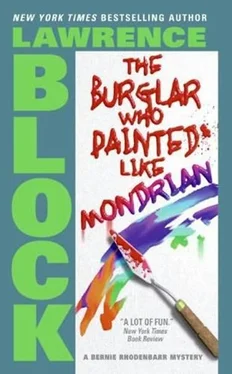

And why not? There was Mondrian’s Composition with Color, placed precisely where it had been on my first visit to the Charlemagne, and positively glowing with its vivid primary colors and sturdy horizontal and vertical lines.

“Makes a powerful statement, doesn’t it?” I leaned back, crossed my legs, made myself comfortable. “And of course it’s why we’re all here. A common interest in Mondrian’s painting is what binds us all together.”

I looked at them again, not as a group but as individuals. Ray Kirschmann was there, of course, sitting in the most comfortable chair and keeping one eye on me and another on the rest of the crowd. That sort of thing can leave a man walleyed, but he was doing a good job of it.

Not far from him, in a pair of folding chairs, were my partner in crime and her partner in lust. Carolyn was wearing her green blazer and a pair of gray flannel slacks, while Alison wore chinos and a striped Brooks Brothers shirt with the collar buttoned down and the sleeves rolled up. They made an attractive couple.

Not far from them, seated side by side on a six-foot sofa, were Mr. and Mrs. J. McLendon Barlow. He was a slender, dapper, almost elegant man with neatly combed iron-gray hair and a military bearing; with his posture he could have been just as comfortable on one of the folding chairs and left the sofa for somebody who needed it. His wife, who could have passed for his daughter, was medium height and slender, a large-eyed creature who wore her long dark hair pinned up in what I think they call a chignon. I know they call something a chignon, and I think that’s what it is. Was. Whatever.

Behind and to the right of the Barlows was a chunkily built man with the sort of face Mondrian might have painted if he’d ever gotten into portrait work. It was all right angles. He was jowly and droopy-eyed, and he had a moustache that was graying and tightly curled hair as black as India ink, and his name was Mordecai Danforth. The man sitting next to him looked about eighteen at first glance, but if you looked closer you could double the figure. He was very pale, wore rimless spectacles and a dark suit with an inch-wide black silk tie, and his name was Lloyd Lewes.

A few feet to Lewes’s right, Elspeth Petrosian sat with her hands folded in her lap, her lips set in a thin line, her head cocked, her expression one of patient fury. She was neatly dressed in Faded Glory jeans and a matching blouse, and was wearing Earth Shoes, with the heel lower than the toe. Those were all the rage a few years back, with ads suggesting that if everybody wore them we could wipe out famine and pestilence, but you don’t see them much anymore. You still see a lot of famine and pestilence, though.

To the right and to the rear of Elspeth, in another of the folding chairs, was a young man whose dark suit looked as though he only wore it on Sundays. Which was fine, because that’s what day it was. He had moist brown eyes and a slightly cleft chin, and his name was Eduardo Melendez.

Читать дальше