“Nary a camera.”

“Then there probably weren’t any pictures.”

“Probably not.”

I turned into Fourteenth Street, headed west. Carolyn was looking at me oddly. I braked for a red light and turned to see her studying me, a thoughtful expression on her face.

“You know something I don’t,” she said.

“I know how to pick locks. That’s all.”

“Something else.”

“It’s just your imagination.”

“I don’t think so. You were uptight before and now you’re all loose and breezy.”

“It’s just self-confidence and a feeling of well-being,” I told her. “Don’t worry. It’ll pass.”

There was a legal parking place around the corner from her apartment, legal until 7 A.M., at any rate. I stuck the Pontiac into it and grabbed up the suitcase.

The cats met us at the door. “Good boys,” Carolyn said, reaching down to pat heads. “Anybody call? Did you take messages like I taught you? Bernie, if it’s not time for a drink, then the liquor ads have been misleading us for years. You game?”

“Sure.”

“Scotch? Rocks? Soda?”

“Yes, yes, and no.”

I unpacked my suitcase while she made the drinks, then made myself sit down and relax long enough to swallow a couple of ounces of Scotch. I waited for it to loosen some of my coiled springs, but before that could happen I was on my feet again.

Carolyn raised her eyebrows at me.

“The car,” I said.

“What about it?”

“I want to put it back where I found it.”

“You’re kidding.”

“That car’s been very useful to me, Carolyn. I want to return the favor.”

I paused at the door, reached back under my jacket. There was a book wedged beneath the waistband of my slacks. I drew it free and set it on a table. Carolyn looked at it and at me again.

“Something to read while I’m gone,” I said.

“What is it?”

“Well,” I said, “it’s not Virgil’s Eclogues .”

I felt good about taking the car back. You don’t spit on your luck, I told myself. I thought of stories of ballplayers refusing to change their socks while the team was on a winning streak. It was high time, I mused, to change my own socks, winning streak or no. A shower would be in order, and a change of garb.

I headed uptown on Tenth Avenue, left hand on the wheel, right hand on the seat beside me, fingers drumming idly. Somewhere in the Forties I snuck a peek at the gas gauge. I had a little less than half a tank left and I felt a need to do something nice for the car’s owner, so I cut over to Eleventh Avenue and found an open station at the corner of Fifty-first Street. I had them fill the tank and check the oil while they were at it. The oil was down a quart and I had them take care of that, too.

My parking space was waiting for me on Seventy-fourth Street, but Max and his owner were nowhere to be seen. I uncoupled my jumper wire, locked up the car, and trotted back to West End Avenue to catch a southbound cab. It was still drizzling lightly but I didn’t have to wait long before a cab pulled up. And it was a Checker, with room for me to stretch my legs and relax.

Things were starting to go right. I could feel it.

Out of habit, I left the cab a few blocks from Arbor Court and walked the rest of the way. I rang, and Carolyn buzzed me through the front door and met me at the door to her apartment. She put her hands on her hips and looked up at me. “You’re full of surprises,” she said.

“It’s part of my charm.”

“Uh-huh. To tell you the truth, poetry never did too much for me. I had a lover early on who thought she was Edna St. Vincent Millay and that sort of cooled me on the whole subject. Where’d you find the book?”

“The Porlock apartment.”

“No shit, Bern. Here I thought you checked it out of the Jefferson Market library. Where in the apartment? Out in plain sight?”

“Uh-uh. In a shoe box on a shelf in the closet.”

“It must have come as a surprise.”

“I’ll say. I was expecting a pair of Capezios, and look what I found.”

“ The Deliverance of Fort Bucklow . I didn’t really read much of it. I skimmed the first three or four pages and I didn’t figure it was going to get better.”

“You were right.”

“How’d you know it would be there, Bern?”

I went over to the kitchen area and made us a couple of drinks. I gave one to Carolyn and accompanied it with the admission that I hadn’t known the book would be there, that I hadn’t even had any particular hope of finding it. “When you don’t know what you’re looking for,” I said, “you have a great advantage, because you don’t know what you’ll find.”

“Just so you know it when you see it. I’m beginning to believe you lead a charmed life. First you run an ad claiming you’ve got the book, and then you open a shoe box and there’s the book. Why did the killer stash it there?”

“He didn’t. He’d have taken it with him.”

“Porlock stashed it?”

“Must have. She drugged me, frisked me, grabbed the book, tucked it away in the closet, and got it hidden just in time to let her killer in the front door. She must have been alone in the apartment with me or he’d have seen her hide the book. She let him in and he killed her and left the gun in my hand and went out.”

“Without the book.”

“Right.”

“Why would he kill her without getting the book?”

“Maybe he didn’t have anything to do with the book. Maybe he had some other reason to want her dead.”

“And he just happened to walk in at that particular time, and he decided to frame you because you happened to be there.”

“I haven’t got it all worked out yet, Carolyn.”

“I can see that.”

“Maybe he killed her first and started looking for the book and came up empty. Except the apartment didn’t look as though it had been searched. It looked as neat as ever, except for the body on the love seat. When I came to, I mean. There was no body there tonight.”

“How about the trunk of the Pontiac?”

I gave her a look. “They did leave chalkmarks, though. On the love seat and the floor, to outline where the body was. It was sort of spooky.” I picked up the book and took it and my drink to the chair. Archie was curled up in it. I put down the book and the drink and moved him and sat down, and he hopped onto my lap and looked on with interest as I picked up the book again and leafed through it.

“I swear he can read,” Carolyn said. “Ubi’s not much on books but Archie loves to read over my shoulder. Or under my shoulder, come to think of it.”

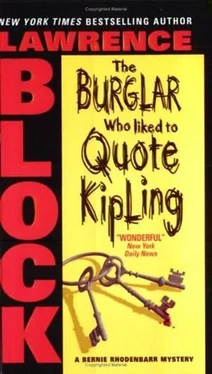

“A cat ought to like Kipling,” I said. “Remember the Just So Stories ? ‘I am the cat who walks by himself, and all places are alike to me.’ ”

Archie purred like a handsaw.

“When I met you,” I said, “I figured you’d have dogs.”

“I’d rather go to them than have them. What made you think I was a dog person?”

“Well, the shop.”

“The Poodle Factory?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, what choice did I have, Bernie? I couldn’t open a cat-grooming salon, for Christ’s sake. Cats groom themselves.”

“That’s a point.”

I read a little more of the book. Something bothered me. I flipped back to the flyleaf and read the handwritten inscription to H. Rider Haggard. I pictured Kipling at his desk in Surrey, dipping his pen, leaning over the book, inscribing it to his closest friend. I closed the book, turned it over and over in my hands.

“Something wrong?”

I shook my head, set the book aside, dispossessed Archie, stood up. “I’m like the cats,” I announced, “and it’s time I set about grooming myself. I’m going to take a shower.”

Читать дальше