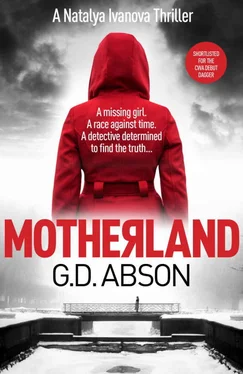

The building was home to a variety of police units including the city’s headquarters for her own Criminal Investigations Directorate. Inside, Sergeant Rogov was waiting for her: ‘Boss wants to see you in Zheglov.’

‘Thanks, he’s already spoken with me.’ She was bemused how Mikhail let Rogov stick so doggedly to him. Perhaps he appreciated some irony in his foul behaviour which she had failed to detect.

‘Not a problem, Natasha.’

She peeled off her jacket and shook the drips to the floor before holding it under her arm to knock on the door. There was an unintelligible call and she entered. Inside, the walls in the meeting room were still nicotine-coloured from the decades of smoking before the public ban took effect four years ago. One side held a portrait of the President in an action shot, throwing an opponent in a St. Petersburg judo competition; another supported a studio picture of Vladimir Vysotsky, who looked a little like the American actor Steve McQueen. Vysotsky had played Gleb Zheglov, a rough cop in the Soviet-era TV series “The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed.” He was universally worshipped by all the menti but she alone seemed to think it was inappropriate to have a photograph of the actor in the room.

Two tables were arranged in a ‘T’ shape with Colonel Vasiliev sitting in his customary armchair at the head. His steel-wool hair was sculpted into a Teddy Boy quiff making him resemble an ageing rock star rather than the head of a city’s serious crimes unit. On the breast of his checked shirt was an enamelled pin badge. From where she stood it was too small to see clearly but she knew it displayed a tiny bear below the tricolour flag with “United Russia” at the bottom. At the adjoining table for subordinates, Mikhail was maintaining an inscrutable expression; opposite him was a well-built man in dress uniform with a layer of stubble for hair.

There were another twenty empty wooden seats widely spaced around the walls of the room for the other detectives in the directorate, and she took one nearest to the three men.

Colonel Vasiliev fingered his United Russia pin badge as he addressed her: ‘Captain Ivanova, I’m sure everyone in the Ministry knows that I am retiring at the end of July. As a senior officer with a distinguished career in the security services, we are honoured to have Major Kirill Dostoynov join the Criminal Investigations Directorate.’

The new major stood and extended his hand for her to shake. That was a good sign, she thought – no saluting and no hesitation, unlike many of her male colleagues. Perhaps Mikhail had judged Dostoynov prematurely. There again, he was probably right in calling him a prick – people didn’t join the FSB out of altruism.

A minute later Sergeant Rogov came in and sat next to her.

‘Captain,’ began Vasiliev, ‘I have been discussing the Zena Dahl case with your husband and Major Dostoynov. If I may summarise, Yulia Federova reported that her friend has been missing since the early hours of yesterday morning.’ He paused for effect. ‘Is it serious?’

She pulled out her notepad. ‘There has been nothing on the girl’s social media and her phone diverts to voicemail. Her suitcases are intact, so are her toiletries. Coupled with this is the testimony of her friend, Yulia Federova, who reported that Miss Dahl has not been returning her calls.’

‘Nevertheless, this may change things.’ Vasiliev took a paper from his desk. ‘Major, please give this to Captain Ivanova.’

Mikhail took the typed sheet from the Colonel and passed it to her; his eyes creased in a smile. The paper had “For Misha” handwritten in a feminine scrawl on the reverse, presumably from a secretary who owed him a favour. For a moment she felt a pang of jealousy wondering what the favour might have been.

All four men were silent while she read it:

MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR OF RUSSIA

MAIN ADMINISTRATION OF THE INTERIOR OF THE CITY OF SAINT-PETERSBURG

193015, city of Saint-Petersburg,

Suvorovsky Prospekt, 50/52

The Data Processing Centre of the Ministry of the Interior of the Russian Federation, Main Administration of the Interior of the city of Saint-Petersburg and Main Administration of the Interior of Leningrad Oblast hold one conviction for Federova Yulia Vladimirovna (date of birth March 7th, 1996; Veliky Novgorod) under Article 159 (Swindling). Sentence: September 6 2012, 12 months, Volgograd. Juvenile Detention.

She looked up as Major Dostoynov addressed the colonel, ‘If I may speak to the Captain?’ It made sense. With Vasiliev retiring, Dostoynov would become her superior unless Mikhail took the top job and forced her to transfer. Mikhail was ambitious but she had made it clear she wouldn’t go willingly and the harm to their relationship would be significant – the conversation had come after sex two weeks ago when he had been more than a little sanguine about remaining in his present position.

Vasiliev scratched a thumbnail against his United Russia badge. ‘Permission given.’

Dostoynov spoke with the slow, confident voice of someone used to having his orders followed: ‘Captain, what happened with the two girls that night?’

‘According to Yulia Federova, they were both drunk and had an argument over a boy. She said Zena left on her own around 1 a.m.’

‘And was she telling the truth?’

‘She claimed she didn’t give her full name to the duty sergeant at Vasilyevsky station because her father had been falsely imprisoned and she doesn’t trust the police.’ She held up the typed sheet with the details of Yulia Federova’s juvenile record. ‘Maybe this was the real reason though.’

‘There was something else I found, Major. When I was in Yulia Federova’s home she gave me permission to search her wardrobe. Inside there was a pair of Ulyana Sergeenko sunglasses and a trouser-suit that cost well beyond her financial means. Zena’s bedroom was full of similar items and my guess is Federova got them from her, one way or another.’

‘So you’re saying the girl had motive and opportunity? Why didn’t you bring her in?’

‘Major, I very much doubt she killed her friend.’

Mikhail joined in; his tone was gentle, and a little condescending, ‘Natalya, we’ve met people before who didn’t seem capable of murder yet that’s exactly what they did. Or if they couldn’t bring themselves to do it, they paid a professional to do the job for them.’

‘I didn’t say she wasn’t capable – history shows that most people are. Yulia Federova was angry, not defensive when I spoke to her. She went to the police station voluntarily and even admitted to having an argument with Zena on the night in question. Unless Federova is very cunning, and I don’t believe she is, then they are the actions of an innocent woman. Also, if the motive had been theft, then why didn’t she steal the clothes in Zena’s apartment? There must be thirty to fifty thousand dollars’ worth.’ She caught a sly smile on Rogov’s mouth and made a mental note to ask Primakov to make an inventory of the wardrobe.

Vasiliev chewed on a plastic pen top and she wondered if he had stopped smoking. ‘Captain, did you get anything else from this supposed witness?’

‘Yulia said Zena was distracted.’

Major Dostoynov opened his palms in a magnanimous motion. ‘Perhaps she was drunk and unhappy. A poor, rich girl deciding to end her sea of troubles in the Neva.’

Vasiliev nodded thoughtfully. ‘Sergeant, do you have anything to add?’

She twisted in her seat to study Rogov and also to allow the Colonel’s full attention to focus on him, rather than her. Rogov was wearing a plain white shirt several sizes too large in order to cover his enormous belly. The cuffs covered his palms and the sleeves hung limply from his arms. There was already a sweat mark at the centre of his chest.

Читать дальше