Wilson ate dinner in his room, then trawled the Internet for news of Bobojon and Hakim. Using different search engines, he looked for February or March news reports from Kuala Lumpur and Berlin, mentioning anyone named Bobojon or Hakim. Nothing. So he tried it again, omitting the names, and looking instead for reports from the same cities using the words “terrorist” and “arrest.” There were dozens of stories, but only two could be considered “hits.”

The first was a short article in Dawn, Malaysia’s biggest English-language newspaper. The story was dated February 24, and recounted the recent arrest of two men at Kuala Lumpur’s Subang Airport.

Sources identified one of the arrested men as Nik Awad, an alleged liaison between Kumpulan Militan Malaysia (KMM) and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI). The second man, traveling on a Syrian passport, was not further identified. Police said the second man attempted to commit suicide at the airport, but was prevented from swallowing a poison capsule.

Both men were detained under provisions of the Internal Security Act. Police are said to be investigating a terrorist plot to attack an American military base in Sumatra.

Wilson read the story three times. The salient facts were three: the time frame, the venue, and the suicide attempt. Late February was about the time he’d dined with Hakim, just before he set sail for Odessa; Hakim had been on the way to Kuala Lumpur; and the suicide attempt, well, it could only be him.

The second story was on the CNN website. It was a March 1 report, datelined Berlin. An antiterrorist investigation had ended in a shootout at the suspect’s apartment. An agent of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV), Clara Deisler, thirty-one, had been killed. The suspect, killed in an exchange of gunfire, was a “guest worker” with links to Islamist groups in Bosnia and Lebanon. The investigation was continuing.

Wilson searched for a follow-up, using Deisler’s name, but all he found were German newspaper articles with the same date as the CNN report. There was no follow-up. Which was strange. Two people had been killed in a gun battle in downtown Berlin. One was a terrorist; the other – a woman, no less – was a government agent. And then… nothing.

So the story was being suppressed.

But was it Bobojon? Wilson couldn’t be sure, but it seemed likely. Among other things, it would explain the phony message left for him in Draft mode. The Germans had Bobojon’s computer. Which probably meant that the CIA did, too. How long, then, before they found out about the Cadogan Bank?

The answer was anyone’s guess. For all Wilson knew, the feds could be watching the bank already. But he doubted that. The FBI and the CIA were bureaucracies like any other, except they were secret. This enabled them to conceal a lot of their blundering. But 9/11 made their modus operandi obvious: They moved slowly, fucked things up, and demanded more “resources.”

Still, they had a lot of resources, so it wasn’t as if you could ignore them.

So the question was: What would he do if he were in their shoes? He thought about it for a moment, and decided that the first thing he’d do was block wire transfers out of the Cadogan account. With so much at stake, “Francisco d’Anconia” would then be expected to contact the bank. At that point, his whereabouts might be traced, or the feds would try to lure him to Jersey.

Before they could do that, though, they’d need to know about the Cadogan Bank, and then they’d have to get the bank’s cooperation.

Did they? Had they? Wilson couldn’t be sure.

He got into Zurich a little after eight the next evening, after traveling nearly fifteen hours. Grimy and exhausted, he contented himself with a snack at a gyro joint in an alley off the Niederhof, where the city’s tourist traps were concentrated. This done, he walked along the quay beside the river, his eyes on the swans, then crossed a footbridge into the old town, where he found a room at the wildly expensive Hotel Zum Storchen.

The next morning, he wandered the streets until he found the vast Jelmoli department store, just off the elegant Bahnhofstrasse. There, he bought new clothes and a leather suitcase. Returning to the hotel, he took a long, hot shower that amounted to a kind of exfoliation. The fire and stink of Bafwasende, the chaos and grime that was Bunia, washed from him until all that was left was the ghost shirt that was his skin, and the injunction:

When the earth trembles,

Do not be afraid

When he checked out, half an hour later, the girl at the reception desk didn’t recognize him – and then, when she did, she giggled. Clad in Armani, Bragano, and Zegna, he seemed, almost, to have stepped off the cover of GQ. Walking to the Bahnhof, he took the first train to the airport, and rented a car.

It was a jet-black Alfa-Romeo convertible. If the weather had cooperated, he’d have driven with the top down all the way to Lake Constance. But the weather had turned, and the sky was spitting at him as he headed east, skirting the edge of the Zurichsee.

There was only one way to find out if anyone was on to him. Move the money. Or try to. If the wire transfer went through, he was still a step ahead of them. If it didn’t… he wasn’t.

Either way, there were problems. If the Cadogan Bank dragged its heels or raised objections, it meant that someone was on to him. And he’d have to run.

If, on the other hand, the bank made no objection to a wire transfer, he still had a problem: What was he going to do with $3.6 million in cash? He’d done the math, and even if it was all in hundred-dollar bills, that much cash would fill a couple of suitcases, at least. And it would weigh a ton. How was he supposed to get the money into the States? Just walk it through Customs? That would be like playing Russian roulette with a derringer. And even if he got the money through Customs, then what? He couldn’t just put it in a bank. The DEA would be all over him.

And there was another problem, as well. Even if the wire transfer went through and he found a way to get the money into the States, there were people who would be looking for him. Not just the FBI and the CIA, but Hakim’s partners in the Lebanese Ministry of Defense. They’d fronted the hash, and they’d expect to be paid for it. This had been Hakim’s responsibility, but now that Hakim was missing, it was up to Wilson.

Of course, the Lebanese didn’t know his name. But they almost certainly knew about Belov (not to mention Zero and Khalid). It wouldn’t take long for the Lebanese to find out that the deal had gone through in Bafwasende, and that Wilson’s bodyguards were killed in Bunia soon afterward. They might even learn that he’d fenced the diamonds through Big Ping. And they would no doubt suspect that he’d decided to keep both his share and theirs.

Not that there was anything they could do about it. Not unless they found him.

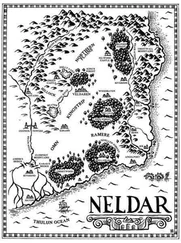

Wilson mused about each of these problems as he drove through the rolling Swiss countryside on the way to tiny Liechtenstein. At three o’clock in the afternoon, he crossed the unmanned border that separates the two countries. Immediately, the road began to climb, cutting back and forth across the mountainside, straightening out when the Alfa rolled into Vaduz, Liechtenstein’s manicured capital. He parked on the street in front of the Banque Privée de Stern, and went inside.

The manager, Herr Eggli, had the look of a young Einstein, with a nimbus of blond hair exploding in every direction. Everything else about him was orderly and precise. His skin was as clear and smooth as a sheet of paper, colorless but for the blush of health in his cheeks. He wore a dark suit and gold-rimmed granny glasses, and spoke English with a British accent. Behind him, floor-to-ceiling windows looked out upon the snowcapped mountains that defined the Rhine Valley, even as they hulked above it.

Читать дальше