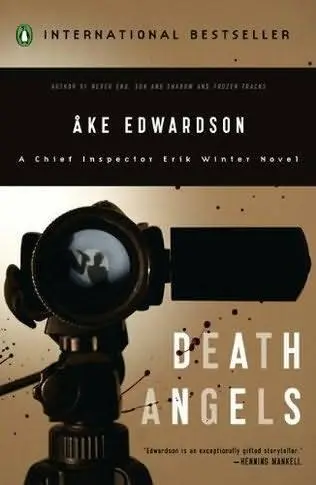

Åke Edwardson

Death Angels

The fourth book in the Erik Winter series, 2009

Translation copyright © Ken Schubert, 2009

Originally published in Swedish as Dans med en angel by Norstedts Forlag, Stockholm.

HE WAS NO LONGER ABLE TO MOVE. HE COULDN’T REMEMBER how long it had been this way. Movement was like a shadow play now.

He knew what was happening to him. He tried to make his way toward the south wall of the room, but the gesture was mostly in his mind, and when he raised his head to see where the sound was coming from…

Once more he felt the coldness between his shoulders and down his back, followed by the heat. He slipped and struck his hip as he fell, then slid along the floor.

He heard a voice.

There’s a voice inside me, he thought, and it’s calling to me, and the voice is me. I know what’s happening to me. Now I’ll go over to the wall, and if I stay calm it’s going to be all right.

Mom! Mom!

He heard a whir like when time freezes and the world stops before your eyes. He couldn’t escape it, and he knew what it was.

Get away from me.

Go away.

I know what’s happening to me. I feel the coldness again. I’m looking down at my leg but I can’t tell which one it is. I see it in the bright light. That’s not the way it was at first. But when the coldness began, the light went on and everything turned to night outside the window.

I hear a car, but it’s going the other direction. Nothing stops out there.

Get away from me.

He could still take care of himself, and if he were just left alone, he would be able to move around the room and over to the door. The man had come in, gone back out and gotten his things, then returned, closed the door and made it night outside.

He still heard the music, but it might be coming from somewhere deep inside. They had played Morrissey, and he knew that the name of the album came from an area on this side of the river-not very far away. He knew a lot about that kind of thing. That was one of the reasons he had come here.

He heard the music again, louder now, but not the whir.

The light was as bright as ever. It ought to hurt, penetrate him.

I don’t feel like it’s hurting me, he thought. I’m not tired. I could leave if I were just able to stand up. I’m trying to say something. Time is slipping away. It’s like when you’re falling asleep, and suddenly you give a start, as if you’re climbing out of a deep pit, and that’s all that matters. When it’s over, you’re frightened and you lie there, incapable of moving.

He didn’t think so much after that. The wires and cables in his head had been clipped in two and his thoughts spilled out and careened around his brain and merged with the blood that was running down his back.

I know it’s blood and it’s mine. I know what’s happening to me. I don’t feel the coldness anymore. Maybe it’s over. What’s next?

I’m up on one knee now. I’m staring into the light, and that’s how I’ll drag myself toward the wall and into the shadows.

Something is coming at me from the side, and I’m turning away from it. Maybe I’m going to make it.

He tried to move toward the refuge that awaited him somewhere, and the music grew louder. There was activity all around him, coming from different angles. He fell and was caught, and he felt himself being lifted up and to the side. He made out the contours of the walls and ceiling as they closed in on him, and he couldn’t tell where one ended and the other began. Then there was no more music.

The last wires holding his thoughts together snapped, leaving him alone with dreams and fragments of memories that he took with him when it was over and silence had descended.

The sound of footsteps faded into the distance, and his thin body slumped against the chair.

lT HAD BEEN THE KIND OF YEAR THAT REFUSES TO LET GO. ITspun every which way and bit its own tail like a rabid dog. Weeks and months seemed to go on forever.

From where Erik Winter sat, the coffin appeared to hover in the air. Daylight poured through a window to his left and lifted it from the bier on the stone floor. Everything merged into a rectangle of sunshine.

He listened to the psalms of death, his lips unmoving. He was surrounded by a circle of silence. It wasn’t the unfamiliar atmosphere that made him feel isolated. Nor was it his grief, but another kind of feeling, akin to loneliness or the void that you stare into when you’re losing your grip.

The warmth of my blood is gone, he thought. It’s as if the path behind me is overgrown with weeds.

***

Rising with the others, Winter walked out into the light and followed the pallbearers to the grave. Once the farewell handfuls of soil had been thrown, there was nothing more to do. Only after he had stood quietly for a few minutes did he feel the January sun caress his face like a hand dipped in lukewarm water.

He walked slowly westward along the street to the ferry dock. The civil war within a man is over, he thought. An armistice has been signed. Now only the past remains, and my grief is just beginning. If only I could simply do nothing for a long time and then start weeding the paths to the future. He smiled wistfully at the low sky.

He climbed aboard and went up to the car deck. The vehicles on the ferry to Gothenburg were covered with dirty snow. They clattered like hell and he put his left hand over his ear. The sun was still out, lucid and impotent over the water. He had removed his leather gloves as the casket was being lowered into the grave, and now he put them on again. He couldn’t remember a time when it was ever this cold.

He stood alone on deck. The ferry chugged away from the island. As it passed a breakwater, he thought about death and the way life goes on long after it loses all meaning. The gestures still come from force of habit but leave nothing in their wake.

***

The ferry restaurant was full. The people seated to his right drifted over toward the big windows.

At first he sat hunched over his table without ordering anything to drink. He waited for the psalms to die down inside his head and then asked for a cup of coffee. A man took the seat next to him.

Winter sat up and unfurled his long frame. “Bertil Ringmar, of all people. Would you like some coffee?”

“Thanks.”

Winter motioned to a waitress.

“I think it’s self-serve.”

“No, here she comes.”

The waitress took Winter’s order in silence, her face oddly transparent in the sunlight. Winter couldn’t tell whether she was looking at him or at the church tower of the receding village. He wondered if you could hear the bells chime when you were on the opposite shore, or on the ferry when it was heading toward the island.

His posture is awkward, Ringmar thought. These tables aren’t made for tall people. He looks like he’s in pain, and it isn’t because of the sunlight in his eyes.

“So here we are again,” Winter said.

“It never ends.”

“No.” Winter watched the waitress put the coffee down in front of Ringmar. The rising steam thinned out at Ringmar’s brow and traced a circle around his head. He looks like an angel, Winter thought. “And what are you doing here?” he asked.

“I’m sitting on the ferry drinking coffee.”

“Why do we always have to split hairs with each other?”

Ringmar took a swig of coffee. “Maybe because we’re both so sensitive to shades of meaning.” He lowered his cup.

Читать дальше