She stared at us.

“Lie down!” he commanded and pulled out his revolver. Though correspondents were not supposed to be armed, most of us carried pistols.

“ Nein – nein -” the girl began to stutter.

I felt parched. All these weeks we had been building ourselves to this. Surely we had meant it. Surely I had meant it too.

And at the same time I felt terrified of Frank. He’d do it and then shoot her. I had shared it all the way, goaded him on; I had wanted it, too. And if I stopped him I was a quitter, a coward.

I laughed, a forced laugh. “Can it, Frank. The hell with her,” I said.

He gave me a wild look, as though he would slam me one. The whole thing could just as well have gone the other way. “It isn’t worth it,” I said. “The war’s over.”

He seemed to sway a little. Then he stuck back his revolver. He laughed. The girl gasped, turned and ran. We climbed into the jeep.

After the war I was living in New York, working on the foreign desk of a news service. One evening at a respectable kind of party of United Nations people and such, I met Ruth. She was there with her husband, an economist. She was sitting across the room from me, and for a moment we weren’t sure we recognized each other.

I got up and went to a refreshment table, and presently she stood beside me. “Yes, it’s me,” she said.

She looked nice. That was always the word, a nice girl, a nice woman. It was twenty-five years since I had seen her.

We filled in about our lives. Ruth had two kids in high school.

We didn’t speak of Judd. When the party broke up and we were both at the door in a little crowd, there was a moment of hesitation between us. Looking at her, I was thinking, It could have been . It all could have been. And it could all come back. And I thought, it could even have been, for Judd.

So I said, as she was about to invite me, “I suppose you’re in the phone book. I’ll give you a ring sometime.”

And I tended my job and married again, and we live in Norwalk.

I’m fifty this year. So is Judd Steiner.

So it happened that one day the news came through that Judd was going to have a parole hearing. And somebody around the place, an old-time newsman like myself, said, “Say, weren’t you…”

Later, I recalled Jonathan Wilk saying something about there being no thought of a chance for freedom for those two, “not until they are forty-five or fifty, when they have come into another phase of life”.

My editors put through this assignment for me to go and interview Judd in prison, for after all, perhaps better than anyone else still alive, they said, I knew the story. What I wrote about him, they said, might have a good deal to do with whether or not he would be released.

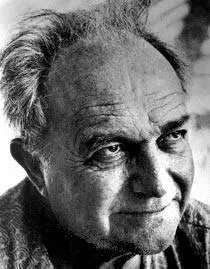

Meyer Levin (October 7, 1905 – July 9, 1981) was an American novelist who commented on the Leopold and Loeb case and wrote the 1956 novel Compulsion inspired by it. Levin had attended college with Leopold and Loeb at the University of Chicago, before the murder of Bobby Franks.

The novel, for which Levin was given a Special Edgar Award by the Mystery Writers of America in 1957, was the basis for the 1957 play Compulsion and the 1959 film based on it. Compulsion was the first ‘documentary’ or ‘non-fiction novel’ (“a style later used in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song” ).

Levin was one of the first American journalists to become aware of the existence of Anne Frank’s diary, and he was also one of the first people to recognize the literary and dramatic potential of this document. He wrote to and met Otto Frank, the father of Anne Frank. Levin became convinced that he had a strong interest in the text, and he later became obsessed when Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett successfully adapted the diary into a hit play while the play Meyer Levin had written was rejected. His 30 years battle to have his play performed and the legal battles that resulted are covered in An Obsession with Anne Frank: Meyer Levin and the Diary by Lawrence Graver, as well as in the French-language book by his wife, Tereska Torres, “Les maisons hantees de Meyer Levin” , published by Editions Phebus (Paris).

***