But, as I mentioned, her health was still good this winter of 1866–67, so I can write about this period with something less than full pain.

As I have also previously mentioned, my mother’s Christian name was Harriet and she had long been a favourite among my father’s circles of famous painters, poets, and up-and-coming artists. After my father’s death in February of 1847, my mother had truly come into her own as one of the preeminent hostesses among the higher circles of artistic and poetic society in London. Indeed, our home at Hanover Terrace (looking out at Regents Park) during the years my mother was hostess there is acknowledged as one of the centres of what some are now calling the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

At the time of my extended visit with her beginning in December of 1866, Mother had realised her long ambition of moving to the countryside and was dividing her time among various cottages she leased in Kent: her Bentham Hill Cottage near Tunbridge Wells, Elm Lodge in the town itself, and her most recent cottage at Prospect Hill, Southborough. I went down to Tunbridge Wells to spend some weeks with her, returning to London each Thursday in order to keep my late-night appointment with King Lazaree and my pipe. Then I would take the train back to Tunbridge Wells on Friday evening, in time to play a game of cribbage with Mother and her friends.

Caroline was not happy with my decision to be gone during all of what some were now calling “the holiday season,” but I reminded her that we never celebrated Christmas to any extent anyway—a man and his mistress obviously were not invited to his married male friends’ homes at any time of the year, but at Christmas-time these male friends accepted even fewer invitations to our home, so it was always the social low-point of our year—but, showing a woman’s resistance to simple reason, Caroline remained vexed that I would be gone all during December and into January. Martha R—, on the other hand, accepting with perfectly good grace my explanation that I wished to get away from London to spend a month and more with my mother, temporarily gave up the room rented to “Mrs Dawson” and returned to Yarmouth and Winterton and her own family.

More and more, I was finding life with Caroline G— tiresome and complicated and my time with Martha R— simple and satisfying.

But my time with Mother that Christmas was the most satisfying of all.

Mother’s cook, who travelled with her everywhere, knew all of my favourite foods from childhood, and often Mother would come into my room in the morning or evening when the tray was delivered and I would enjoy my repast in bed while we carried on our conversations.

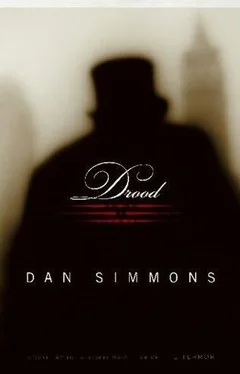

When I had fled London I was filled with a terrible sense of guilt and foreboding concerning the presumed death of the boy named Gooseberry, but after a few days at Mother’s cottage, that dark cloud had moved away. What had the child’s unusual real name been? Guy Septimus Cecil. Well, what nonsense to think that young Guy Septimus Cecil had actually been murdered by the dark forces of Undertown as represented by the foreign sorcerer Drood!

This was an elaborate game, I reminded myself, with Charles Dickens playing one game on his side, the elderly Inspector Field playing his corresponding but not identical game on the other side, and poor William Wilkie Collins caught in the middle.

Gooseberry murdered, indeed! The Inspector shows me a few tattered cloths sprinkled with dried blood—dog’s blood for all I knew, or the vital fluid from one of the thousands of feral cats that roamed the slums from whence Gooseberry sprang—and now I was expected to fly all to pieces and to do Inspector Field’s bidding even more assiduously than I had to date.

Drood had moved beyond being a phantasm and had become more of a shuttlecock in this insane game of badminton between a disturbed author with an obsession for play-acting and an evil old gnome of an ex-policeman with too many secret motives to count.

Well, let them play their game without me for a while. The hospitality of Tunbridge Wells and my mother’s cottage served me well for December and early January. Along with recovering some of my health—my rheumatical gout was strangely better there in Kent, although I continued administering doses of the laudanum, albeit in lower quantities—my sleep came easier, my dreams grew less clouded, and I began to think more earnestly about the elegant plot and fascinating characters of The Serpent’s Eye (or possibly The Eye of the Serpent ). Although the serious research would have to wait until I returned full-time to London and the library at my club, I could—and did—jot down preliminary notes and a rough outline, often writing from my bed.

Occasionally I thought of my duties as detective in discerning whether young Edmond Dickenson had been murdered by Charles Dickens, but my interview with Dickenson’s solicitor had been singularly unenlightening—except for the shock of learning that Charles Dickens himself had been appointed the youth’s guardian-executor in the last months of the young man’s need for such care—and even my keen novelist’s mind could find no next step to take in the investigation. I decided that when I returned to London life, I should discreetly ask around my club if anyone had heard of the comings and goings of a certain squire named Dickenson, but other than that, I could see no obvious direction to take in the investigation.

By the second week of December, the only thing that was disturbing my peace of mind was the lack of an invitation to Gad’s Hill Place for Christmas.

I was not sure that I would have accepted the invitation that year (there had been subtle but obvious tensions between the Inimitable and myself in the preceding months, my suspicion of the author’s being a murderer among them), but I certainly expected to be invited . After all, Dickens had more or less said the last time I saw him that I would be receiving the usual invitation to be a houseguest.

But no invitation arrived at my mother’s cottage. Each Thursday afternoon or Friday mid-day, before or after my visit to King Lazaree’s den, I would drop in on Caroline to pick up my mail and to make sure that she and Carrie had enough money to meet all accounts, but still there arrived no invitation from Dickens. Then, on the sixteenth of December, my younger brother, Charles, came down to Southborough to spend the day and brought with him an envelope addressed to me in Georgina’s distinctive hand.

“Has Dickens said anything to you about Christmas?” I asked my brother as I searched for my knife to open the invitation.

“He has said nothing to me,” Charley said sourly. I could tell that his ulcers—or what I then thought were his ulcers—were hurting him. My talented brother was listless and downcast. “Dickens told Katey that there would be the usual houseful of guests.… I know the Chappells are coming down to Gad’s Hill for a few days, and Percy Fitzgerald for the New Year.”

“Hmm, the Chappells,” I said while unfolding the letter. These were Dickens’s new business partners in the reading tours and, I thought, interminable boors. I decided that I would definitely not stay at Gad’s Hill for the full week that I usually tarried if the Chappells were going to be there for any extended length of time.

Imagine my surprise when I read the letter, which I reproduce here in its entirety—

My Dear Wilkie—

This is a pretty state of things! — That I should be in Christmas Labour while you are cruising about the world, a compound of Hayward and Captain Cook! But I am so undoubtedly one of the sons of Toil—and fathers of children—that I expect to be presently presented with a smock frock, a pair of leather breeches, and a pewter watch, for having brought up the largest family ever known with the smallest disposition to do anything for themselves.

Читать дальше