Dickens’s laughter came down on the soft breeze. “Then by all means, Captain, you must come up!”

DICKENS HAD BEEN WRITING at his table and he was setting his manuscript pages into his oiled-leather portfolio as I came in. His left foot was propped up on a pillow which sat on a low stool, but he took his leg down as I entered. Although Dickens waved me to the only other chair in the room, I was too agitated to sit and contented myself with pacing from one window to the next and back.

“I am so delighted you chose to accept my invitation,” Dickens was saying as he secured his writing utensils and buckled the portfolio closed.

“It was time,” I said.

“You look a bit heavier, Wilkie.”

“You look thinner, Charles. Except for your foot, which seems to have put on a few pounds.”

Dickens laughed. “Our dear and mutual friend Frank Beard has warnings for both of us, does he not?”

“I see less of Frank Beard these days,” I said, moving from the east-facing window to the south-facing one. “Frank’s lovely children have declared war on me since I revealed the hypocrisies of Muscular Christianity.”

“Oh, I hardly think it is the revelation of hypocrisy that has made the children angry at you, Wilkie. Rather the heresy of impugning their various sports heroes. I have not had the time to read it myself, but I hear that the instalments of Man and Wife have ruffled quite a few feathers.”

“And sold more and more copies as it has done so,” I said. “Before this month is out, I plan to publish it in book form, in three volumes, with the firm of F. S. Ellis.”

“Ellis?” said Dickens, getting to his feet and reaching for a silver-headed cane. “I wasn’t aware that the Ellis firm published books. I thought it dealt with cards, calendars, that sort of thing.”

“This is their first venture,” I said. “They will be selling on commission and I will be receiving ten percent on every copy sold.”

“Marvellous!” said Dickens. “You seem somewhat restless—perhaps even agitated—today, my dear Wilkie. Would you care to join me in a walk?”

“ Can you walk, Charles?” I was eyeing his new cane, which was indeed a cane, of the long-handled type one saw being carried by lame old men, rather than the sort of dashing walking stick preferred by young men such as myself. (As you may remember, Dear Reader, I was 46 in this summer of 1870, while Dickens was 58 and showed every year and month and more of that advanced age. But then, several people had recently commented on the grey in my beard, my ever-increasing girth, my problems catching my breath, and a certain hunched-over quality my tired body had assumed of late, and some had been so impertinent as to suggest that I was looking much older than my years.)

“Yes, I can walk,” said Dickens, taking no offence at my comment. “And I try to every day. It is getting late, so I do not suggest a serious walk to Rochester or some other daunting destination, but we might manage a stroll through the fields.”

I nodded and Dickens led the way down, leaving—one presumes—the portfolio with his unfinished manuscript of The Mystery of Edwin Drood there on his chalet worktable where anyone might come in off the highway and filch it.

WE CROSSED THE ROAD towards his house but then went around the side yard, past the stables, through the rear yard where he had once consigned his correspondence to a bonfire, and out into the field where Sultan had died some autumns earlier. The grasses here that had been dead and brown then were green and high and stirring in the breeze today. A well-worn path led off towards the rolling hills and a scrim of trees that marked the path of a broad stream that ran towards the river that ran to the sea.

Neither of us was running this day, but if Dickens’s walking pace had been diminished, I could not discern it. I was huffing and puffing to keep up.

“Frank Beard tells me that you’ve had to add morphine to your pharmacopoeia in order to sleep,” said Dickens, the cane in his left hand (he had always carried his stick in his right hand before) quickly rising and falling. “And that, although you’ve told him you discontinued the practice, a syringe he lent you some time ago has gone missing.”

“Beard is a dear man,” I said, “who often lacks discretion. He was keeping the world informed as to your pulse rate during your final reading tour, Charles.”

My walking partner had nothing to say to that.

Finally I added, “The daughter of my servants, George and Besse—still servants of mine for the time-being at least—had been pilfering things. I had to send her away.”

“Little Agnes?” cried Dickens. “Stealing? Incredible!”

We crossed the brow of the first low hill so that Gad’s Hill Place, the highway, and its attending line of trees all fell behind. The path wound parallel to the tree line here for a way and then crossed a little bridge.

“Do you mind if we stop for a moment, Charles?”

“Not in the least, my dear Wilkie. Not in the least!”

I leaned on the little arched bridge’s railing and took three sips from my silver flask. “An uncomfortably warm day, today, is it not?”

“You think so? I find it close to perfect.”

We headed off again, but Dickens was either tiring or walking slowly for my benefit.

“How is your health, Charles? One hears so many things. As with our dear Frank Beard’s ominous rumblings, one doesn’t know what is true. Are you recovered from your tours?”

“I feel much better these days,” said Dickens. “At least some days I do. Yesterday I told a friend that I was certain I should be living and working deep into my eighties. And I felt as if this were true. Other days… well, you know about the hard days, my friend. Other days, one does what one must to honour commitments and to honour the work itself.”

“And how is Edwin Drood coming along?” I asked.

Dickens glanced at me before replying. With the terrible exception of Dickens’s savaging of The Moonstone, we rarely, either one of us, offered to discuss work in progress with the other. The ferruled base of his cane swung with a sweet, summery swish-swish against the tall grass to either side of the path.

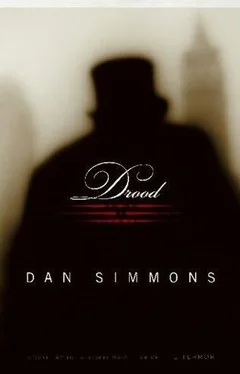

“ Drood is coming along slowly but well, I think,” he said at last. “It is a much more complicated book, in terms of plot and twists and revelations, than most I have attempted in the past, my dear Wilkie. But you know that! You are the master of the mystery form! I should have submitted all my novice’s problems to you for a Virgil’s guidance in the ways of mystery and suspense long before this! How goes your Man and Wife ?”

“I look to finish it in the next two or three days.”

“Marvellous!” cried Dickens once again. We were out of sight of the brook now, but its soft sounds followed us as we passed through more trees and then came out into another open field. The path continued winding towards the distant sea.

“When I do finish it, I wonder if you would do me a great favour, Charles.”

“If it is within my poor and failing powers, I shall certainly attempt to do so.”

“I believe it is within our powers to solve two mysteries on the same night… if, that is, you’re willing to go on a secret outing with me on Wednesday or Thursday night.”

“A secret outing?” laughed Dickens.

“The mysteries would have a greater chance of being solved if neither you nor I told anyone—no one at all—that we were going anywhere that evening.”

“Now that does sound mysterious,” said Dickens as we came to the brow of a hill. There were large barrow stones—Druid stones, the children and farmers called them, although they were nothing of the sort—scattered and heaped there. “How could keeping our outing a secret improve the chances at success of that outing?”

Читать дальше