Alexander Smith - Unbearable Lightness of Scones

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alexander Smith - Unbearable Lightness of Scones» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Unbearable Lightness of Scones

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Unbearable Lightness of Scones: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Unbearable Lightness of Scones»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Unbearable Lightness of Scones — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Unbearable Lightness of Scones», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Four, sometimes,” corrected Maria. “And Mah Jong one day a week.”

“She likes her Mah Jong,” said Jack, smiling at his wife. “I don’t care for it myself. All that click-clicking as you put the pieces down. Gets on my nerves.”

“Do you play Mah Jong?” asked Maria.

“No,” said Elspeth. “I’m afraid I don’t.”

“Nor me,” said Matthew.

There was a silence. Then Matthew spoke. “Do you mind my asking, Uncle Jack,” said Matthew. “Do you mind my asking what it is that you do out here?”

“Import/export,” said Jack quickly. “Goods in. Goods out. Not that we’re sending as many goods out as we used to. China is seeing to that. They make everything these days. Everything. How can Singapore compete? You tell me that, Matthew. How can we compete?”

It appeared that he was waiting for an answer, and so Matthew shrugged.

“Precisely,” said Jack.

A further silence ensued, broken, at last, by Maria. “Do you like cats?” she asked.

Matthew looked to Elspeth, who looked back at him. “Yes, although I… we don’t have one.”

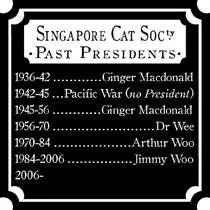

“We like them a lot,” Jack said. “And I’m actually president of the Cat Society of Singapore. Not the Singapore Cat Club

– they’re a different bunch. The Cat Society.” He looked down at the table in modesty.

“Jimmy Woo was the president before Jack,” explained Maria. “He’s one of the big Siamese breeders here in Singapore. His father, Arthur Woo, was the person who really got the breed going here.”

Jack cleared his throat. “Well, that’s a matter of opinion, my dear. Old Dr. Wee was pretty influential in that regard. And there was Ginger Macdonald well before him. He shot his cats when the Japanese arrived, you know. Rather than let them fall into their hands.”

Maria looked grave, and cast her eyes downwards, as if observing a short silence for the Macdonald cats. Then she looked up. “It’s a pity that you’re here this week rather than next,” she said. “We’ve got our big show then. People come from all over. Kuala Lumpur. Lots of people come down from KL just to see the show. Henry Koo, for instance.”

“No, he’s Penang. Not KL,” said Jack.

“Are you sure?”

“Pretty sure. The Koos have that big hotel up there. And they breed pretty much the finest Burmese show cats in South-East Asia. A whole dynasty of grand champions.”

Maria looked doubtful. “Then it’s another Koo,” she said. “The Koo I’m thinking of definitely came from KL. Maybe he was Harry Koo, not Henry.”

The conversation continued much in this vein throughout dinner. Jack was keen to discover what Matthew thought of Raffles and Maria came up with shopping recommendations for Elspeth. Then, just as coffee was being served, the small band struck up and several couples at the other tables went out onto the dance floor.

“I’d be delighted if you’d dance with me,” Jack said to Elspeth. He threw a glance at Matthew and then nodded in the direction of Maria. Matthew took the hint and asked her if she would care to dance with him.

Jack was a good dancer, and Elspeth found herself led naturally and confidently around the dance floor. As they passed the other couples, polite smiles were exchanged, and Jack nodded to the men. “I’m very glad that Matthew phoned,” he said. “I’ve been out of touch, you know. It’s like that out here. You get caught up in your own life and you forget about family back home.”

“You must have a busy time,” she said.

“Oh we do. There’s never a dull moment. Especially when the show comes up.”

They returned to the table and Maria suggested that Elspeth might care to accompany her to attend to her make-up.

“We’ll meet you ladies back in the bar,” said Jack. “I’ll show Matthew the card room.”

The women went off, and Matthew walked with his uncle back through the lobby.

“What an enjoyable evening,” said Jack. “A jolly good evening. Good of you to get in touch, Matthew.”

“I’m glad that we’ve met again,” said Matthew. “I recall your last visit, you know. I remember your cigarette holder.”

Jack gave a chuckle. “Yes. One remembers the little details. I find that too.” He paused. “Tell me, Matthew, you’ll have heard the talk, won’t you?”

Matthew looked puzzled. “The talk?”

“Yes,” said Jack. “The talk. People said, you see… Well, you’ll know what they said. About you being… being mine rather than your father’s. That talk.”

They had almost crossed the lobby. Matthew stopped in his tracks. “I’m not sure what you mean.”

Jack took the cigarette-holder out of his pocket and started to fiddle with it. “The talk was that you were my son. I heard some of it myself.”

Matthew found it difficult to speak. His throat felt tight; his mouth suddenly dry. “I don’t know what to say… I’m sorry. This is a bit of a surprise.”

Now Jack became apologetic. “Oh, I’m terribly sorry, old chap. It never occurred to me that you wouldn’t know. But I do assure you, there was never any truth in it. Idle gossip. That’s all. Now, let’s go and take a look at the card room. They might be playing bridge, but we can take a peek and won’t disturb anybody. This way, old chap.”

Later, in the taxi on the way back to Raffles, Matthew sat quite silent.

“That didn’t go well, did it?” said Elspeth, slipping her hand into his.

“Ghastly,” said Matthew.

“You’re very quiet,” said Elspeth. “Has it depressed you?”

Matthew nodded, mutely – miserably. He remembered the discussion between his parents: why had they lowered their voices; why had the visit of Uncle Jack been such a fraught occasion? Why had Uncle Jack looked at him so closely – scrutinised him indeed – at their earlier meeting? Suddenly it all seemed so clear.

I am the son of the president of the Cat Society of Singapore, thought Matthew. That’s what I really am.

60. Huddles, Guddles, Toil and Muddles

While Matthew and Elspeth were returning to Raffles Hotel, back in Scotland Street, Domenica Macdonald, anthropologist and observer of humanity in all its forms, was hanging up a dish towel in her kitchen. Matthew and Elspeth had dined in the Tanglin Club, while Domenica had enjoyed more simple fare at her kitchen table: a couple of slices of smoked salmon given to her by Angus Lordie (rationed: Angus never gave her more than two slices of salmon) and a bowl of Tuscan Bean soup from Valvona & Crolla. She savoured every fragment of the smoked salmon, which was made in a small village outside Campbeltown by Archie Graham, according to a recipe of his own devising. Angus claimed that it was the finest smoked salmon in Scotland – a view with which Domenica readily agreed; she had tried to obtain Archie’s address from Angus, but he had deliberately, if tactfully, declined to give it. Thus did Lucia protect the recipe for Lobster à la Riseholme in Benson’s novels, Domenica thought, and look what happened to Lucia: her hoarding of the recipe had driven Mapp into rifling through the recipe books in her enemy’s kitchen. She might perhaps mention that to Angus next time she asked; not, she suspected, that it would make any difference.

With her plates washed up and stored in the cupboard and her dish towel hung up on its hook, Domenica took her blue Spode teacup off its shelf and set it on the table. She would have a cup of tea, she decided, and then take a position on what to do that afternoon. She could possibly… She stopped, realising that she actually had nothing to do. There was no housework to be done in the flat; there were no letters to be answered; there were no proofs of an academic paper to be corrected – there was, in short, nothing.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Unbearable Lightness of Scones»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Unbearable Lightness of Scones» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Unbearable Lightness of Scones» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.