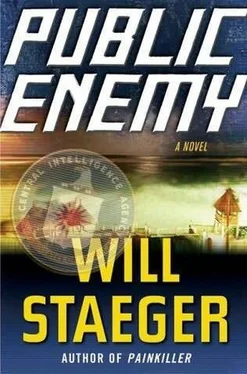

All the more corroborating evidence on the identity of the snuffer-outers.

As with the aboveground portion of the former riverfront factory-or prison camp, or movie theater, or whatever the fuck it had been, he thought-there wasn’t much to see in the cave. They’d burned whatever had been left in here too, the blackened, moist, smelly soil that coated the floor of the chamber consistent with the ash and coals he’d been kicking around up top. Neither Cooper nor Borrego could stand up straight except near the middle of the cavity; they shone their flashlights around the room in search of anything besides the evident rock, moss, dirt, and puddles.

“Maybe they stole from the Indians too,” the Polar Bear said from somewhere behind Cooper. “Kept the loot in here.”

“Maybe,” Cooper said idly.

“Whatever it was, though, seems to me it wouldn’t keep.”

“What do you mean,” Cooper said, peering around.

“Right now’s dry season. My guess’d be half the year, maybe more, this room’s a pond. Underwater.”

Cooper, brain dulled from too many days with too little food and too much humidity and exercise, took upward of thirty seconds to hear the coupler engage within the confines of his head. Trying to fend off some of the fatigue and flex his brain, he made the connection his mind was trying to tell him it had already made:

Underwater.

Along the back wall of the cavern, the floor was two or three feet deeper than the spot where he stood now. It was there, at the back of the cave, where the puddles stood. He walked to the back wall, moving slowly so as not to stir up too much mud, and shone his flashlight into the water as he worked his way along the wall.

The puddles reminded him of blackened tide pools. He poked around with his foot, feeling from behind the protective sheath of his steel-toed boot. Some of the puddles were deeper than others-two inches here, six there.

You’re burning something, and part of that something happens to be underwater, it could be you didn’t burn all of-

He heard the muted scraping noise first. Cooper and Borrego met each other’s gaze for an instant, and then Cooper pulled his boot out of the puddle, crouched down, and slipped his hand into the muck to find what it was he’d nudged. He came out with a short length of rotting wood.

Holding it up in the light, he could see it was close to eight or nine inches long, two or three inches wide in one direction, and thinner than his pinkie in the other. Its edges were jagged, blackened, rotten-a piece of it fell off and slopped into the puddle as Cooper rotated it in the beam of his flashlight-but when he got it turned around, Cooper, and Borrego beside him, saw that there was actually something to see.

The wood on the back side of the board, which had been submerged in the mud-or algae, or whatever else it is you find in a mud puddle in a rain forest cave-was pale. The color on the back side of the board was probably close to the original, natural color of the wood before the fire and rot had got to its other side.

Along this pale side of the board, stenciled in black, were two complete and legible letters, and half of a third. The three letters, at least by Cooper’s guess, were ICR. Below the letters were the rounded tops of an incomplete sequence of numbers, Cooper thinking it might be a serial number or ID labeling of some kind, but this portion of the markings on the wood seemed impossible to read.

Cooper looked at Borrego and pointed the wood in his direction.

“Mean anything to you?” he said. “Appears to be part of a crate, and you’re the biggest shipping magnate in the cave.”

“‘ICR,’ you mean? Not offhand.”

Cooper put the rotting piece of wood in his pocket, kicked and felt his way through the remainder of the puddles, found some other boards, splinters, and chunks of wood-all similar to the one in his pocket, but none with any markings.

Then he stood and took in the sight of the massive, hunched form of Ernesto Borrego.

“Might mean something to somebody somewhere, though,” he said.

Borrego nodded. “Otherwise we came all this way for a stick.”

Cooper almost smiled again.

Borrego’s bass rumble of a voice came next.

“Had enough?” he said.

“Of this place? For a lifetime.”

Borrego turned, pointed his flashlight beam toward the exit of the cave, and led the way out.

“Good,” the Polar Bear said. “’Cause I may be dead, but I’ve still got a business to run.”

Laramie was in her second hour of sleep following forty-eight without when an obnoxiously loud and persistent knocking dredged her from her pool of slumber.

“I hear you.”

She got her legs around and found the floor, retrieved a pair of jeans, and pulled them on beneath the oversize Lakers T-shirt she always wore to bed-another detail it seemed Ebbers had instructed his minions to heed. A look through her peephole revealed Wally Knowles, looking as chipper as she’d seen him, the man even showing the presence of mind to put on his hat before coming down to see her. She checked her watch-3:43 A.M.-then unlatched the chain and opened the door.

“I think we may have found our boy,” Knowles said.

Laramie perked up. He must have meant they’d got a hit on their custom computer setup-that it had yielded a photograph of Benny Achar taken before he’d adopted his new identity.

When Laramie asked Knowles if that was what he meant, the author jerked his head sideways and disappeared from the door frame, headed back in the direction of his room.

“Better to show,” he said, “than tell.”

They’d imported some serious computer equipment during the past few days, which Knowles had set up on his own in his room. Even to Laramie-who preferred to leave anything with computers to the tech guy who serviced their workstations in Langley-the setup was impressive. A pair of gunmetal gray Power Macintosh towers anchored a system featuring two huge flat-panel monitors, a laser printer, and a box with a strip of green and yellow lights down its front that Laramie figured for the cable modem. As she came in behind Knowles, Laramie saw that Cole was on the phone, using-as instructed-the room’s land line instead of his cell phone. On one of the monitors she could see a grainy, smudged image of a life raft overflowing with people. The boat looked to be out on the ocean, but was about to make landfall-some of the people on the boat were reaching for a dock Laramie could just barely make out on the right-hand side of the picture.

Cole continued with his phone call, offering Laramie a lazy salute with his off hand as Knowles took the seat in front of the monitor and motioned for Laramie to join him for a look. He worked the mouse and the image rewound. Laramie noticed it happened digitally, in that way where pixels and squares could be seen as the image shifted backward in time.

“We got lucky,” Knowles explained, “considering such a measly portion of the actual available pool of images from the past twenty years has been digitized and stored in the consortium’s archives. Most of what has been digitized comes from broadcast and print media, however, which turned out to be useful.”

The image started playing, the raft-almost a small barge, she thought-rolling in the waves. There wasn’t any audio, but Laramie could see a buffeting of the surface of the water, as though from a helicopter-the source of the camera shooting the video, she assumed. The men crammed aboard the boat appeared very animated, most of them gesturing toward the right side of the image, where Laramie knew the dock would soon appear on-screen.

“This is a boat full of Cuban refugees,” Knowles said as the video played, “shot by a local news chopper as the vessel docked somewhere south of Miami.”

Читать дальше

![Томас Гарди - Джуд неудачник [Литрес, Public Domain]](/books/437392/tomas-gardi-dzhud-neudachnik-litres-public-domain-thumb.webp)