It made me feel better about myself, better about the crazy shithole we were currently residing in, and honestly, better about the fact that I was going home soon. She was going to be in prison for many more years. If I could forgive, it meant I was a strong, good person who could take responsibility for the path I had chosen for myself, and all the consequences that accompanied that choice. And it gave me the simple but powerful satisfaction of extending a kindness to another person in a tough spot.

It’s not easy to sacrifice your anger, your sense of being wronged. I still cautioned Nora regularly that today might be the day she drowned, and she laughed nervously at my mock-threats. Sometimes her sister offered to help with the drowning, if Nora was being annoying. But we were able to settle into a feisty rapport, like all ex-lovers who have a lot of water under the bridge but have elected to be friends. The things that I had liked about her over a decade earlier-her humor, her curiosity, her hustle, her interest in the weird and transgressive-all those things were still true; in fact, they had been sharpened by her years in a high-security prison in California.

We served each other as a barrier against the freaks, of which this small unit had an astonishing array. In addition to poor suicidal Connie, there were several bipolar arsonists, an angry and volatile bank robber, a woman who had written a letter threatening to assassinate John Ashcroft, and a tiny pregnant girl who would seat herself next to me and start running her hands through my hair, crooning. I saw more temper tantrums and freakouts in a few weeks than I had in many months in Danbury, all of which the CO basically ignored. There was no SHU for women in Chicago (we were one floor above the men’s SHU), so the only disciplinary action that could be taken against us was sending a female off to the Cook County Jail, the largest in the nation at ten thousand inmates. “You do not want to go there!” warned Crystal, the mayor, who seemed to know what she was talking about.

Now that we had been in the MCC for a couple of weeks, the sisters and I saw that there were in fact some sane women present. At first no one really came near us; it took a while to realize that some of the residents of the twelfth floor were scared of us-after all, we three were hardened cons from real prison. But after a bit they must have recognized that we were “normal” like them, and then they made eager overtures: a couple of sweet and friendly Spanish mamis, a very short sports fanatic, and a hilarious Chinese lesbian who introduced herself to me hopefully with the line “I like your body!”

We were instantly elevated as authorities on anything and everything involving the federal prison system. When we explained that in fact “real prison” was much more bearable than our present surroundings, they were perplexed. They also wanted legal advice, lots of it, and I found myself repeating, “I am not a lawyer. You have to ask your attorney…” But all of them had court-appointed lawyers who were rarely accessible. There was a bizarre black Batphone on the wall, which was supposed to tap directly into the public defender’s office. “Fat fucking lot of good that does us,” complained one of the arsonists.

I did not have the representation problems of my fellow prisoners. One day I was called out of the unit, told I was going “to court,” and sent down to R &D to sit in a holding cell for hours. Finally I was handed off to my escorts, two big, young Customs agents, federal cops. I’m not sure what they were expecting, but it wasn’t me. When I turned my back to them to be cuffed, the guy doing the honors got rattled.

“She’s too small. They don’t even fit her!” He sounded anguished.

His counterpart stuck a thick finger between the cuffs and my wrist and said he thought we were good.

In the worldview of these burly, clean-cut young guys, I was clearly not supposed to be resident in this fortress. I probably looked too much like their sister, their neighbor, or their wife.

After being locked away for so many weeks, I enjoyed the ride through the streets of Chicago. At the federal building on South Dearborn, I was taken upstairs to a nondescript conference room and deposited, with the less-rattled officer to guard me. We sat across the table from each other, in silence, for fifteen minutes. I wasn’t looking at him, but I could tell he was watching me, which I guess was his job. He seemed to be getting agitated. He shifted in his chair, looked at the clock, looked at me, shifted again. I thought he was just bored. With prison Zen, I waited for whatever was going to happen next. Finally he couldn’t stand it anymore.

“You know, we all make mistakes,” he said.

I turned my eyes to him. “I know that,” I replied.

“What were you, an addict?”

“No, I just made a mistake.”

He was silent for a moment. “You’re just so young.”

This amused me. It must be the yoga. He was definitely younger than me.

“My offense is more than eleven years old. I’m thirty-five.” His eyebrows shot toward his hairline. He had no idea what to do with this information.

Mercifully the door opened, ending the conversation. It was my lawyer, Pat Cotter, with the Assistant U.S. Attorney and a roast beef sandwich. “Larry said roast beef was your favorite!”

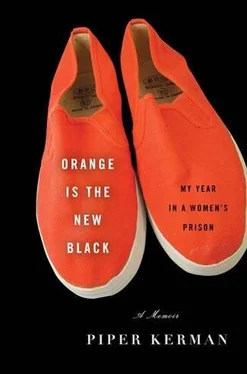

I wolfed it down in as ladylike a fashion as I could muster. I had almost forgotten about my orange attire, but now I felt a little self-conscious. He also brought me a root beer. This is what a top-shelf, white-shoe criminal defense gets you. I was very happy to see him.

Pat explained that because I would appear as a government witness, the AUSA, the woman who had put me in jail (well actually, that was me; she just prosecuted) got to prepare me. He again reminded me that my plea agreement obligated me to cooperate. He would stay with us, but I had no legal protection per se. Nor was I in any legal risk, as long as I didn’t perjure myself. I assured him I had no plans for that, then pressed him about getting me out of the MCC and back to Danbury. He said he would see what he could do; Jonathan Bibby’s trial date had already been pushed back twice. I knew that meant “Fat chance.”

I was very tired when I got back to our fortress prison. “You’ll get your turn,” I told Nora and Hester/Anne. We had managed to get moved into a six-person cell with three other women, so now in addition to everything else, we were roommates. I went to sleep.

THE BIGGEST problem with the MCC was that there was nothing to do. There was a pathetic pile of crap books, decks of cards, and the infernal televisions, always on, always at full volume. There had been nothing to do in Oklahoma City either, but there the surroundings were spotless and serene, with about ten times as much space. Mercifully in Chicago we received mail, and letters and books began arriving for me. I shared my books with my bunkies.

When you are deep in misery, you reach out to those who can help, people who can understand. I picked up a pen and wrote to the only person on the outside who could begin to grasp my situation, my pen pal Joe, the ex-bank robber. He wrote me back immediately.

Dear Piper,

Got your letter. Thanks for reminding me of how much I hated the Los Angeles Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC). I laughed like a mental patient when you told me you are withholding your birth date from your chatty, amateur astrologist bunkmate. That’s hilarious. Must be driving her nuts.

So I officially met your boy Larry when I was in NYC last month. A cool guy. We chilled at a nice coffee shop near where you live. It’s good that you have a loving place to land when you are officially released altogether from the halfway house.

Talk about places to land, I was trapped in Oklahoma City (during my transfer from California to Pennsylvania) for 2 months. And I was a high-security risk so I spent that entire time locked in the hole. In the middle of summer. I suffered. I’m so fucking happy that I’m done with doing time. I got good at it, but I never want to be good at it again. That’s one talent I don’t mind squandering.

Читать дальше