“Are you from Massachusetts?” I asked shyly.

“My Bahston accent must be wicked bad. I’m from Nawh-wood.” She laughed.

That accent made me feel a lot better. We started talking about the Red Sox and her stint as a volunteer on Kerry’s last senatorial campaign.

“How long are you here for?” I asked innocently.

Rosemarie got a funny look on her face. “Fifty-four months. For Internet auction fraud. But I’m going to Boot Camp, so when you take that into account…” and she launched into a calculation of good time and reduction of sentence and halfway house time. I was shocked again, both by her casual revelation of her crime and by her sentence. Fifty-four months in federal prison for eBay fraud?

Rosemarie’s presence was comfortingly familiar-that accent, the love for Manny Ramirez, her Wall Street Journal subscription, all reminded me of places other than here.

“Let me know if you need anything,” she said. “And don’t feel bad if you need a shoulder to cry on. I cried nonstop for the first week I was here.”

I made it through the first night in my prison bed without crying. Truth was, I didn’t really feel like it anymore, I was too shocked and tired. Earlier I had sidled my way into one of the TV rooms with my back to the wall, but news of the Martha Stewart trial was on, and no one was paying any attention to me. Eyeing the bookshelf crammed with James Patterson, V. C. Andrews, and romance novels, I finally found an old paperback copy of Pride and Prejudice and retired to my bunk-on top of the covers, of course. I fell gratefully into the much more familiar world of Hanoverian England.

My new roommates left me alone. At ten P.M. the lights were turned off abruptly, and I slipped Jane Austen onto my locker and stared at the ceiling, listening to Annette’s respirator machine-she had suffered a massive heart attack shortly after arriving in Danbury and had to use it at night to breathe. Miss Luz, almost imperceptible in the other bottom bunk, was recovering from breast cancer treatment and had no hair on her tiny head. I was beginning to suspect that the most dangerous thing you could do in prison was get sick.

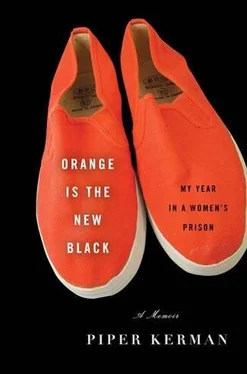

CHAPTER 4. Orange Is the New Black

The next morning I and eight other new arrivals reported for a day-long orientation session, held in the smallest of the TV rooms. Among the group was one of my roommates, a zaftig Dominican girl who was an odd combination of sulky and helpful. She had a little tattoo of a dancing Mephistopheles figure on her arm, with the letters JC. I tentatively asked her if they stood for Jesus Christ-maybe protecting her from the festive devil?

She looked at me as if I were completely insane, then rolled her eyes. “That’s my boyfriend’s initials.”

Sitting on my left against the wall was a young black woman to whom I took an instant liking, for no reason. Her rough cornrows and aggressively set jaw couldn’t disguise the fact that she was very young and pretty. I made small talk, asking her name, where she was from, how much time she had to do, the tiny set of questions that I thought were acceptable to ask. Her name was Janet, she was from Brooklyn, and she had sixty months. She seemed to think I was weird for talking to her.

A small white woman on the other side of the room, on the other hand, was chatty. About ten years my senior, with a friendly-witch aspect, straggly red hair, aquiline nose, and weathered creases in her skin, she looked as if she lived in the mountains, or by the sea. She was back in prison on a probation violation. “I did two years in West Virginia. It’s like a big campus, decent food. This place is a dump.” She said this all pretty cheerfully, and I was stunned that anyone returning to prison could be so matter-of-fact and upbeat. Another white woman in the group was also back in for a violation, and she was bitter, which made more sense to me. The rest of the group was a mixed bag of black and Latino women who leaned against the walls, staring at the ceiling or floor. We were all dressed alike, with those stupid canvas slippers.

We were subjected to an excruciating five-hour presentation from all of Danbury FCI’s major departments-finance, phones, recreation, commissary, safety, education, psychiatry-an array of professional attention that somehow added up to an astonishingly low standard of living for prisoners. The speakers fell into two categories: apologetic or condescending. The apologetic variety included the prison psychiatrist, Dr. Kirk, who was about my age and handsome. He could have been one of my friends’ husbands. Dr. Kirk sheepishly informed us that he was in the Camp for a few hours each Thursday and “couldn’t really supply” any mental health services unless it was “an emergency.” He was the only provider of psychiatric care for the fourteen hundred women in the Danbury complex, and his primary function was to dole out psych meds. If you wanted to be sedated, Dr. Kirk was your guy.

In the condescending category was Mr. Scott, a cocky young corrections officer who insisted on playing a question-and-answer game with us about the most basic rules of interpersonal behavior and admonished us repeatedly not to be “gay for the stay.” But worst of all was the woman from health services, who was so unpleasant that I was taken aback. She firmly informed us that we had better not dare to waste their time, that they would determine whether we were sick or not and what was medically necessary, and that we should not expect any existing condition to be addressed unless it was life-threatening. I silently gave thanks that I was blessed with good health. We were fucked if we got sick.

After the health services rep was out of the room, the red-headed violator piped up. “Jesus F. Christ, who peed in her Cheerios?”

Next a big bluff man from facilities with enormously bushy eyebrows entered the room. “Hello, ladies!” he boomed. “My name is Mr. Richards. I just wanted to tell you all that I’m sorry you’re here. I don’t know what landed you here, but whatever happened, I wish things were different. I know that may not be much comfort to you right now, but I mean it. I know you’ve got families and kids and that you belong home with them. I hope your time here is short.” After hours of being treated as ungrateful and deceitful children, this stranger showed us remarkable sensitivity. We all perked up a bit.

“ Kerman!” Another prisoner with a clipboard stuck her head into the room. “Uniforms!”

I was lucky to arrive at prison on a Wednesday. Uniform issue was done on Thursdays, so if you self-surrendered on a Monday, you might be pretty smelly after a few days, depending on whether you sweat when you are nervous. I followed the clipboard down the hall to a small room where uniforms were distributed, leftovers from when the place had been a men’s facility. I was given four pairs of elastic-waist khaki pants and five khaki poly-blend button-down shirts, which bore the names of their former wearers on the front pockets; Marialinda Maldonado, Vicki Frazer, Marie Saunders, Karol Ryan, and Angel Chevasco. Also: one set of white thermal underwear; an itchy boiled-wool hat, scarf, and mittens; five white T-shirts; four pairs of tube socks; three white sports bras; ten pairs of granny panties (which I soon discovered would lose their elastic after a couple washings); and a nightgown so enormous it made me giggle-everyone referred to it as a muu-muu.

Finally, the guard who was silently handing me the clothing asked, “What size shoe?”

“Nine and a half.”

He pushed a red and black shoebox toward me, containing my very own pair of heavy black steel-toed shoes. I hadn’t been so happy to put on a pair of shoes since I found a pair of peep-toed Manolo Blahniks at a sample sale for fifty dollars. These beauties were solid and held the promise of strength. I loved them instantly. I handed back those canvas slippers with a huge smile on my face. Now I was a for-real, hardened con. I felt infinitely better.

Читать дальше