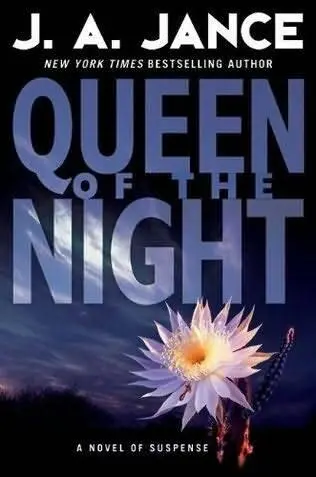

J A Jance

Queen of the Night

The fourth book in the Brandon Walker series, 2010

In memory of Tony Hillerman, Old White-Haired Man, and all his Brought-Back Children

They say it happened long ago that a young woman of the Tohono O’odham, the Desert People, fell in love with a Yaqui warrior, a Hiakim, and went to live with him and his people, far to the South. Every evening, her mother, Old White-Haired Woman, would go outside by herself and listen. After a while her daughter’s spirit would speak to her from her new home far away. One day Old White-Haired Woman heard nothing, so she went to find her husband.

“Our daughter is ill,” Old White-Haired Woman told him. “I must go to her.”

“But the Hiakim live far from here,” he said, “and you are a bent old woman. How will you get there?”

“I will ask I’itoi, the Spirit of Goodness, to help me.”

Elder Brother heard the woman’s plea. He sent Coyote, Ban, to guide Old White-Haired Woman’s steps on her long journey, and he sent the Ali Chu Chum O ’odham, the Little People-the animals and birds-to help her along the way. When she was thirsty, Ban led her to water. When she was hungry, the Birds, U’u Whig, brought her seeds and beans to eat.

After weeks of traveling, Old White-Haired Woman finally reached the land of the Hiakim. There she learned that her daughter was sick and dying.

“Please take my son home to our people,” Old White-Haired Woman’s daughter begged. “If you don’t, his father’s people will turn him into a warrior.”

You must understand, nawoj, my friend, that from the time the Tohono O’odham emerged from the center of the earth, they have always been a peace-loving people. So one night, when the Hiakim were busy feasting, Old White-Haired Woman loaded the baby into her burden basket and set off for the North. When the Yaqui learned she was gone, they sent a band of warriors after her to bring the baby back.

Old White-Haired Woman walked and walked. She was almost back to the land of the Desert People when the Yaqui warriors spotted her. I’itoi saw she was not going to complete her journey, so he called a flock of shashani, black birds, who flew into the eyes of the Yaqui and blinded them. While the warriors were busy fighting shashani, I’itoi took Old White-Haired Woman into a wash and hid her.

By then the old grandmother was very tired and lame from all her walking and carrying.

“You stay here,” Elder Brother told her. “I will carry the baby back to your people, but while you sit here resting, you will be changed. Because of your bravery, your feet will become roots. Your tired old body will turn into branches. Each year, for one night only, you will become the most beautiful plant on the earth, a flower the Milgahn, the whites, call the night-blooming cereus, the Queen of the Night.”

And it happened just that way. Old White-Haired Woman turned into a plant the Indians call ho’ok-wah’o, which means Witch’s Tongs. But on that one night in early summer when a beautiful scent fills the desert air, the Tohono O’odham know that they are breathing in kok’oi ’uw, Ghost Scent, and they remember a brave old woman who saved her grandson and brought him home.

Each year after that, on the night the flowers bloomed, the Tohono O’odham would gather around while Brought Back Child told the story of his brave grandmother, Old White-Haired Woman, and that, nawoj, my frie n d, is the same story I have just told you.

San Diego, California

Saturday, March 21, 1959, Midnight

58º Fahrenheit

L ong after everyone else had left the beach and returned to the hotel, and long after the bonfire died down to coals, Ursula Brinker sat there in the sand and marveled over what had happened. What she had allowed to happen.

When June Lennox had invited Sully to come along to San Diego for spring break, she had known the moment she said yes that she was saying yes to more than just a fun trip from Tempe, Arizona, to California. The insistent tug had been there all along, for as long as Sully could remember. From the time she was in kindergarten, she had been interested in girls, not boys, and that hadn’t changed. Not later in grade school when the other girls started drooling over boys, and not later in high school, either.

But she had kept the secret. For one thing, she knew how much her parents would disapprove if Sully ever admitted to them or to anyone else what she had long suspected-that she was a lesbian. She didn’t go around advertising it or wearing mannish clothing. People said she was “cute,” and she was-cute and smart and talented. She didn’t know exactly what would happen to her if people figured out who she really was, but it probably wouldn’t be good. She did a good job of keeping up appearances, so no one guessed that the girl who had been valedictorian of her class and who had been voted most likely to succeed was actually queer “as a three-dollar bill.” That was what some of the boys said about people like that-people like her. And she was afraid that by talking about it, what she was feeling right now would be snatched away from her, like a mirage melting into the desert.

She had kept the secret until now. Until today. With June. And she was afraid, if she left the beach and went back to the hotel room with everyone else and spoke about it, if she gave that newfound happiness a name, it might disappear forever as well.

The beach was deserted. When she heard the sand-muffled footsteps behind her, she thought it might be June. But it wasn’t.

“Hello,” she said. “When did you get here?”

He didn’t answer that question. “What you did was wrong,” he said. “Did you think you could keep it a secret? Did you think I wouldn’t find out?”

“It just happened,” she said. “We didn’t mean to hurt you.”

“But you did,” he said. “More than you know.”

He fell on her then. Had anyone been walking past on the beach, they wouldn’t have paid much attention. Just another young couple carried away with necking; people who hadn’t gotten themselves a room, and probably should have.

But in the early hours of that morning, what was happening there by the dwindling fire wasn’t an act of love. It was something else altogether. When the rough embrace finally ended, the man stood up and walked away. He walked into the water and sluiced away the blood.

As for Sully Brinker? She did not walk away. The brainy cheerleader, the girl who had it all-money, brains, and looks-the girl once voted most likely to succeed would not succeed at anything because she was lying dead in the sand-dead at age twenty-one-and her parents’ lives would never be the same.

Los Angeles, California

Saturday, October 28, 1978, 11:20 p.m.

63º Fahrenheit

A s the quarrel escalated, four-year-old Danny Pardee cowered in his bed. He covered his head with his pillow and tried not to listen, but the pillow didn’t help. He could still hear the voices raging back and forth: his father’s voice and his mother’s. Turning on the TV set might have helped, but if his father came into the bedroom and found the set on when it wasn’t supposed to be, Danny knew what would happen. First the belt would come off and, after that, the beating.

Danny knew how much that belt hurt, so he lay there and willed himself not to listen. He tried to fill his head with the words to one of the songs he had learned at preschool: “You put your right foot in; you put your right foot out. You put your right foot in, and you shake it all about. You do the hokey-pokey and you turn yourself around. That’s what it’s all about.”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу