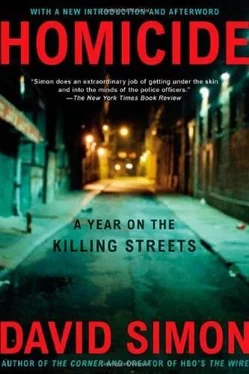

For the detectives, the rule of thumb is that if you think about it, if you allow the imagery to be about human beings rather than evidence, you will be led to some strange and depressing places. Insisting on this distance is an acquired skill, and for new detectives, an established rite of passage. New men are measured by their willingness to watch a body disassembled and then adjourn to the Penn Restaurant, on the other side of Pratt Street, for the three-egg special and a beer.

“The real test of a man,” says Donald Worden, reading the menu one morning, “is whether or not he’s willing to substitute that nasty pork roll for the bacon.”

Even Terry McLarney, the closest thing to a philosopher in the homicide unit, has trouble finding anything more than black comedy in the autopsy room. When it is his turn to walk in that small space between the living and the dead, his empathy for the forms on the metal tables is largely limited to his ongoing and thoroughly unscientific survey of livers.

“I like to look for the more derelict-looking guys, the ones who look like they’ve had a hard life,” explains McLarney, deadpan. “If they open ’em up and the liver is all hard and gray, I get depressed. But if it’s pink and puffy, hey, I’m happy all day.”

On one discomfiting occasion, McLarney was in the autopsy room when one case appeared on the rounds sheet with the explanation that although the victim had no medical history, he was known to drink beer every day. “I read that and figured, What the fuck,” McLarney mused. “I might as well just find an empty table, lie down and unbutton my shirt.”

Of course, McLarney knows better than to think it can all be laughed off. The line between life and death isn’t so thick and straight that a man can stand on it every morning, cracking jokes with impunity as the doctors wield scalpel and knife. Once, in a rare moment, McLarney even tries to find words for something deeper.

“I don’t know about anyone else,” he says, serving up a platitude to the others in the homicide office one afternoon, “but whenever I’m down there for an autopsy, I can pretty much convince myself that there is a God and there is a heaven.”

“The morgue makes you believe in God?” asks Nolan, incredulous.

“Yeah, well, if not heaven, then someplace where your mind or your soul goes after you die.”

“Ain’t no heaven,” says Nolan to the rest of the group. “You look around that room down there and you know we’re all just meat.”

“No,” says McLarney, shaking his head. “I believe we go somewhere.”

“Why’s that?” asks Nolan.

“Because when the bodies are all laid out like that, all the life is just gone and you know that there’s nothing left. They’re so empty. You can look at their faces and know they’re completely empty…”

“So?”

“So, it’s got to go somewhere, right? It doesn’t just disappear. They’ve all got to have somewhere else to go.”

“So their souls go to heaven?”

“Hey,” says McLarney, laughing, “why not?”

And Nolan smiles and shakes his head, giving McLarney time to wander off with his seminal theologies intact. After all, only the living can argue for the dead, and McLarney is alive; they are not. By virtue of that one undeniable fact, he is entitled to win with the weakest argument.

FRIDAY, AUGUST 19

Dave Brown pilots the Cavalier to within a block of the blue emergency lights, close enough to observe the general outline of the scene.

“I’ll take this one,” he says.

“You really are a piece of shit,” says Worden from the passenger seat. “Why don’t you just drive up and take a look at it first before deciding?”

“Hey, I’m deciding now.”

“Maybe you want to see if there’s a lockup first?”

“Hey,” says Brown again, “I’m deciding now.”

Worden shakes his head. Protocol demands that when two detectives are in a car and heading for a scene, one detective signs on as the primary before anything about the murder is known. By this unspoken agreement, those unseemly arguments in which one detective accuses another of grabbing dunkers and dumping whodunits are kept to a minimum. By waiting until the scene is within sight, Dave Brown is trampling around the edges of the rule, and Worden, true to form, is letting him know it.

“Whatever happens,” Worden says, “I’m not helping you with this case.”

“Did I ask for your fucking help?”

Worden shrugs.

“It’s not like I got a look at the body.”

“Good luck,” says Worden.

Brown wants this murder for no other reason than the location of the crime scene, but as reasons go, it’s pretty good. For one thing, the Cavalier is now parked in the 1900 block of Johnson Street in South Baltimore’s bottom, and South Baltimore’s bottom is deep in the bowels of Billyland. Stretching from Curtis Bay to Brooklyn and from South Baltimore on through Pigtown and Morrell Park, Billyland is a recognized geographic entity among Baltimore cops, a subculture that serves as the natural habitat for the descendants of West Virginians and Virginians who left the coal mines and the mountains to man Baltimore’s factories during the Second World War. To the chagrin of the established white ethnic groups, the billies swarmed into the red brick and Formstone rowhouses in the southern reaches of the city-an exodus that defined Baltimore as much as the northern movement of blacks from Virginia and the Carolinas during the same era. Billyland has its own language and logic, its own social framework. Billies don’t reside in Baltimore, they live in Bawlmer; it is the Appalachian influence that gives the language in the white sections of the city much of its twang. And although the advent of fluoride has allowed even the truest of billies to retain more of their teeth with each passing generation, nothing prevents their allowing their bodies to be treated like virgin canvas by the East Baltimore Street tattoo artists. Similarly, a billy girl might feel compelled to call police when her boyfriend throws a National Premium bottle at her head, but she will just as surely leap with claws bared on a Southern District uniform’s back the moment he arrives to take her man away.

For Baltimore’s cops, hard-core billyness is generally regarded with as much disdain and humor as the hard-core ghetto culture. If nothing else, this attitude provides some proof that it is class consciousness, more than racism, that propels a cop toward a contempt for the huddled masses. And in the homicide unit in particular, the working coalition of black and white detectives tends to drive home the point. Just as Bert Silver is excepted from the general dislike of female officers, so are Eddie Brown and Harry Edgerton and Roger Nolan regarded as special cases by white detectives. If you are poor and black and your name is floating around somewhere in the BPI computer, then you are a yo and a toad and-depending on how unreconstructed the mind of the cop-maybe even a brain-dead nigger. If, however, you are Eddie Brown at the next desk over, or Greg Gaskins down at the state’s attorney’s office, or Cliff Gordy on the circuit court bench, or any other member of the taxpaying classes, then you are a black man.

A similar logic applies in Billyland.

You may come from the same mountain stock as the rest of Pigtown, but by a detective’s reasoning, that alone doesn’t make you a true billy. Maybe you’re just another white boy; maybe you finished twelfth grade at Southern High and nailed down a decent job and moved out to Glen Burnie or Linthicum. Or maybe you’re like Donald Worden, who grew up in Hampden, or like Donald Kincaid, speaking in a mountain drawl and sporting that tattoo on the back of one hand. On the other hand, if you’ve spent half your life drinking at the B &O Tavern on West Pratt Street and the other half shuttling back and forth from the Southern District Court for theft, disorderly conduct, resisting arrest and possession of phencyclidine, then to a Baltimore detective you most certainly are a billy boy, a white-trash redneck, a city goat, a dead-brained cul-de-sac of heredity, spawned in the shallow end of a diminishing gene pool. And if you happen to get in the way of a Baltimore cop, he’ll probably be happy to tell you as much.

Читать дальше