You are keeping her safe for me, I hear the Dark Man say, and I tear on out of the high grass and across the road like perdition’s flames. The girl sees me coming and lets out a scream, so high and sharp it pains my ears. The rattler sees me too, and lets fly as I come up, but he is just a sorry crawling vermin and I am the Dark Man’s Good Dog, and I catch him behind his head and crush his bones in one bite. I whip him back and forth a bit, ’til I’m sure he knows he’s dead, and drop him in the road. Then I look around.

She’s crouched down behind the oak tree, staring at me, eyes all wide and frightened. She starts in coughing, holding on to the oak to stay upright. I sit down in the road. No point in going back to the high grass now.

“You’re his dog,” she whispers when her breath comes back. “The black dog. You’re real. It’s real.”

Stupid woman. Why you been sitting out here five Sundays in a row, catching your death of the ague if you don’t believe? People only believe the things they can see, and touch, and have. Like that man, that fool from Memphis, handed the Dark Man his guitar and then grabbed his arm, squeezed him like, just to see if he was solid.

The Dark Man don’t like to be touched.

She coughs some more, then pulls out a bottle, honey and cold tea and cheap whiskey. She hunkers down beside the oak, swigging and coughing and staring at me, and we spend the rest of the night that way, she and I and the skeeters, and come the dawn I pick up the rattler and go home and her still sitting there, stunned-like.

Sixth Sunday

The Dark Man pours the powder out of the packet. It sifts down into my fur, spilling all around me on the porch. I can smell all the things that went into it, and my nose wrinkles up. Sweet and kinda spoiled, like honey and curdled milk mixed up.

Remember, she can hear you in there, so no talking, he says.

Yes, boss.

He runs his finger across the diamond-patterned skin tacked out on the door, gives the rattle a flick with his finger, and smiles. It’s just a little smile, but he knows I see it.

Go on now, he says.

I take off out the shack and down the road. It’s close on to midnight. Mr. Moon is still fat and bright, and my shadow chases me all the way to the crossroads.

It’s a hot night, muggy like, but she’s all wrapped up in a raggedy shawl. She coughs, and it racks her. There’s circles under her eyes, and she’s all pale and peaked, a sight thinner than she was when all this started. That cold is a long time going. She leaves off coughing, catches her breath, looks up and sees me.

“Dog,” she says. Then she stretches out her hand, waggling her fingers. “C’mere dog.”

Usually they don’t touch me right away. One time, this boy from Charleston wouldn’t even let me near and I had to chase him through the grass, all the way to the riverbank. That was a treat.

I go on over and sit near her and I don’t put my ears back or growl or show my teeth or nothing. She puts her hand right on my head. She’s not a bit afraid.

“Good dog,” she says, and my tail thumps in spite of me. “Good dog that saved my life.” Her hand moves to the back of my ears. I turn my head a little, and she runs her hand down my spine. Then she finds a sweet spot on my shoulder and commences scratching, and my mutinous left hind foot starts to dance, tappity tap against the dirt.

She rummages around in her stinky bag, comes up with a sandwich.

“You want some of my chicken sandwich?”

Stupid woman. I grab the sandwich out of her hand, gulp it down so fast she don’t see it go. Chicken is good. Best when you catch it yourself, but good any way you get it.

“Hey!” she says, and I duck my head away from her hand. She laughs, and scratches behind my ear again. “That was my supper, dog, but I guess you earned it, killing that bad old snake.”

Supper? That little bit of chicken and brown bread?

She yawns, and leans back against the tree. “I’m so sleepy,” she says. “But I guess I can rest a while, with you here to watch over me.” And she with her hand on my back, she closes her eyes and drifts away, down into dreamland, and I go with.

We’re standing outside a little tottery tarpaper house. Raggedy curtains drooping in the front window, front yard all mud and junk; an old water pump, a pile of car tires, door off a chicken coop. Clothes on the line, tired sheets and towels and a pair of man’s coveralls, ripped and faded. Somewhere here, someplace not right now, I can hear a child crying.

She’s beside me in the road, and she looks different. Stronger, more meat on her bones. Ugly boots gone, good walking shoes on her feet, big backpack, all shiny and new-smelling hooked on her shoulder. And something else, something I can’t determinate.

“Here I go,” she says, and turns her back on the house. She starts down the road, big long steps, and she doesn’t look back, but I do. There’s a face staring at us from that front window, looking angry and sad both at once, and then the tatty curtains twitch, and the face is gone.

“Dog! You coming?” she says, and I run to catch up.

We walk a long time. Mr. Moon lights the way. There’s honeysuckle in the air, thick and sweet, and the further we get from that house the happier she is. Her step gets lighter, like she’s shucking off some burden, and she starts in laughing from time to time.

We walk on and on. I flush a fat rabbit and chase it a while. She takes a big meat sandwich out of her bag and gives me half, and we drink our fill from a spring running by the road. She picks up an old stick and throws it as she walks along, and I bring it on back and she throws it again.

By and by the road under our feet changes, from hard-packed dirt to blacktop, smooth and oily and smelling from tar. The sky is changed now, the wind is dry and hot, the trees and brush all gone. And it’s a puzzlement to me; I can smell the desert spread out all around us, sand and heat and open sky, but there’s water up ahead too, a powerful lot of it.

“Look, dog. There it is.” Off in the distance I can see a city, tall buildings and lights shining and blinking, and cars, and people-more than I’ve ever seen. And something else, a thick, rank smell the Dark Man taught me. Money. Bright lights and noise and money, that’s the place her heart yearns for.

She pulls a pack of cards from her pocket, does a one-hand shuffle like she was born with the pasteboards in her hands. She spreads the cards out to make a fan and flutters them back and forth, and the ace of spades jumps out and dances along above us in that hot dry wind a second before she catches it neat as neat and slides it back in.

“They do what I tell them, now,” she says. “I’m going to be the queen of the tables, dog, how’s that sound to you?”

That’s what’s different about her, what I couldn’t place. This dream is the future, after the Dark Man learns her what she wants to learn.

“Cards? You doing all of this to learn cards?” I ask.

“I’m going to be a queen,” she says again, not paying me any mind. She’s shuffling the cards again, makes the joker jump up this time. The breeze picks the card and pulls it up out of the deck, and it lands on the blacktop at my feet before she can catch it. The joker is the Dark Man, and he winks up at me. She makes a little tch sound and picks up the card, puts it back in the deck.

Her clothes are changed. She’s wearing a dress, shiny spangles and beads, her hair is long and kind of curly, on her feet little bitty shoes with tall heels, and her fingers all covered in rings.

You’re going to end up in the cupboard with all the rest, I think. But I won’t speak. He’ll beat me enough for what I’ve said already, I don’t want more than that. No more. Nope.

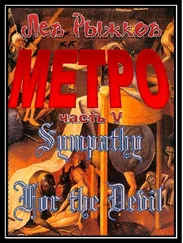

Читать дальше