His mother had argued ferociously against the purchase, persisting even after he pulled his prize into the driveway for the first time.

“I don’t see why you need a foreign car, Carl. And it cost the earth! Why, for what you spent, you could have bought a-”

“It’s my money, Mother,” Carl had replied, calmly. “I saved it myself. Besides, it’s not just a car; it’s an investment. Ten years from now, it will be worth more than I paid for it.”

“I don’t see how that could be,” she said, using that passively stubborn tone he hated so.

“Well, I guess we’ll see who’s right when the time comes,” he said, attempting to dismiss the issue.

“It’s just too much money. Especially on your salary, Carl.”

“I don’t really have much in the way of expenses, Mother. It’s not as if I had to pay rent someplace.”

Catching the implied threat, his mother had subsided.

But that was over a year ago. Tonight, Carl was alone in his perfect Reich car. He slipped the column shift into reverse, tenderly let out the clutch, and backed out of his driveway.

1959 October 05 Monday 02:51

Finished with his meal, Dett took a short length of rope from his suitcase and stood ramrod-straight. He held one end of the rope in his right hand, draped the length of it down his back, and grasped the other end with his left. Dett pulled at both ends of the rope, lightly at first. Then he increased the tension until the rope vibrated, the muscles in his arms and shoulders screaming in protest. He willed away the pain, breathing steadily and rhythmically through his nose, counting slowly to one hundred. He switched hands and repeated the exercise.

Dett stood under a hot shower for several minutes. Wearing only a towel around his waist, he took a small pair of steel springs from his suitcase. Placing one in each hand, he began to compress them, over and over, until his forearms locked and the springs dropped from nerveless fingers.

He stood up, rotating his head on his neck, first in one direction, then the other, making five full circles each time. Next, he unscrewed the top of a small hexagonal jar, dabbed his finger into the dark-red paste inside, and applied it to each of his hands. He dry-washed his hands until the paste was fully distributed and he felt a familiar tingling sensation.

Spreading fresh towels over the tatty carpet, Dett lay on his stomach, placing his hands, palms-down, on either side of his face. Then he raised his neck all the way back until his sternum was barely touching the improvised mat, and held the position for a count of six. He did four repetitions. Then he rolled over onto his back and slowly drew his body into a ninety-degree angle, sitting straight up, back perfectly aligned. He lowered himself to the mat, moving in small, smooth increments, feeling the tightening of his abdominal muscles with each repetition.

On arising, Dett walked to the far wall, placed his spread fingers against it, and pushed until his entire upper body cramped.

Dett stepped away from the wall, arms dangling at his sides, the middle finger of each hand barely touching his thighs. Slowly, he moved his hands behind his back until they met, and clasped them together. He took a deep breath through his nose, held it for a few seconds, then expelled it as he brought his hands up behind his back and over his shoulders in one smooth, continuous motion. When the arc was completed, his clasped hands were at his waist.

Dett held that position for a full minute, then repeated the entire exercise. He went back under the shower, toweled off, and lay down on the bed in the darkness, holding his derringer.

After a while, he closed his eyes. But he did not sleep.

1959 October 05 Monday 02:59

“What’s all that you writing, brother?”

“It’s what I found in that man’s room,” Rufus said. “Look for yourself.”

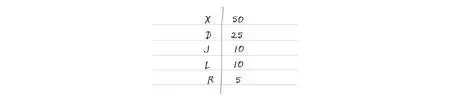

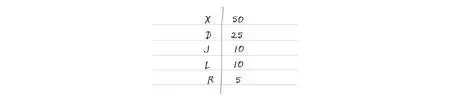

Kendall stepped behind Rufus. He saw a grade-school notebook-white ruled paper, bound in a hard black cover with a random pattern of white splotches. Rufus opened the book, as if displaying a trophy. The right-hand page was divided by a lengthwise line, creating two columns:

Under the columns was a string of addresses, all public buildings: the city library, the police station, the post office… and three different banks.

At the very bottom of the page, in the far right corner, was a ten-digit number.

“I thought you said there wasn’t nothing in his room,” Kendall said.

“There wasn’t,” Rufus replied. “But when I meet with the boss greaseball, Mister Dioguardi himself, this is going to be what I tell him I copied down, see?”

“Does it mean anything?”

“Only the long number at the bottom. And that one’s a pay phone, in a part of Chicago they call Uptown. White man’s territory. Ivory picked it up one day, on his route, and it went right into our information book. Now we finally got a use for it. Only I wrote it backwards, like it was in code.”

“You going to tell the man that, Omar?”

“What?”

“That it’s in code, man. Otherwise, what good is-?”

“Brother, listen to me. The last thing I would ever do is explain anything to those kind of people. See, niggers is stupid. We don’t know nothing. We just good little monkeys, taking orders, stepping and fetching. We smart enough to take money for stuff they tell us to do, but that’s about it. You understand?”

“No,” Kendall said, his voice tightening. “I know how you always be saying-”

“Yeah, K-man. I always be saying, but you don’t always be listening. Look, we’re not a ‘minority’ for nothing, understand? That means just what it says-there’s more of them than there are of us. Always going to be like that, too. So we learn to slip and slide, hide what we got. And what we got the most of is brains, brother. Those ‘race leaders’ of ours,” Rufus said, his voice clotting with disgust, “they’re all about convincing the white man he’s wrong about us. We’re not ignorant apes that only want to fuck their women-with our giant Johnsons, don’t forget-no, not us. We good boys. They should call us ‘Negroes,’ not niggers, or jungle bunnies, or spooks. They should let us go to school with them, work in their businesses, ride on their buses.”

Rufus unconsciously shifted into his natural orator’s voice, but kept the volume down. “But the ‘good’ whites, they don’t see us as equals. No, to them, we’re pets. And you got to take care of your pets. Make sure they get enough food and water, right? See, pets, they don’t want to be free. No, they just want to be taken care of.

“So let them think we’re all like that. Why do you think we’re raising those puppies out back, brother? Whitey thinks we all scared of German shepherds, because that’s the dogs they use on us down south. White man thinks, I got me a German shepherd, I never have to worry about no nigger burglar, okay? But dogs, they’re like children. They don’t have no natural hatred of any race. They have to learn that. So we’re raising our own.”

“Our own children, too,” Kendall said, proudly.

“Yes, brother. But you can’t teach a child if you can’t feed a child. The child will not respect the father who doesn’t take care of him and protect him. You got millions of black children in this country, and who’s their father? Uncle Sam, that’s who. The white man, the Welfare. Same thing.

“We got to have our own, K-man. Our own businesses, our own money. Our own land. And the only way we even get that chance is to sneak up on Whitey.”

“But the NAACP-”

“Let them walk their own road, brother. Let them eat white rice, even though everybody knows the brown rice is better for you. Let them straighten their hair, bleach their skin. Let them marry whites, they love them so much. You know where the word ‘nigger’ comes from?”

Читать дальше