Michael Walsh - Early Warning

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Walsh - Early Warning» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Early Warning

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Early Warning: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Early Warning»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Early Warning — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Early Warning», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The things that occupied the human mind. Substitution ciphers, mirror writing, inverted mirror writing…those damn mystery writers never knew when to leave well enough alone.

The third was a bit more complex: It was unsigned.: UG RMK CSXHMUFMKB TOXG CMVATLUIV. Any first-year student at the Wyoming Cryptography School, where he had gone as an undergraduate, could spot that: Have His Carcase by Dorothy L. Sayers, the creator of Lord Peter Wimsey. “We are discovered. Save Yourself.” Piece of cake.

The fourth was a series of numbers: 317, 8, 92, 73, 112, 79, 67, 318, 28, 96, 107, 41, 631, 78, 146, 397, 118, 98, 114.

Beale Ciphers, not that that was much of a help. The three ciphers, first published in a pamphlet in Virginia in 1885, were said to show the way to a great treasure, but only the second cipher had ever been cracked-it turned out to be a numerological correspondence to the wording of the Declaration of Independence which, when read en clair, said:

I have deposited in the county of Bedford, about four miles from Buford’s, in an excavation or vault, six feet below the surface of the ground, the following articles:…The deposit consists of two thousand nine hundred and twenty one pounds of gold and five thousand one hundred pounds of silver; also jewels, obtained in St. Louis in exchange for silver to save transportation… The above is securely packed in iron pots, with iron covers. The vault is roughly lined with stone, and the vessels rest on solid stone, and are covered with others…”

Lots of luck with that. No one-not even the finest minds at NSA or CIA, just screwing around in their spare time, had broken the other two; if they had, they might have found the buried treasure and retired very wealthy men. So wealthy, in fact, that they might even have been able to afford their houses in Potomac and Great Falls.

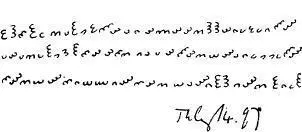

The fifth was the familiar series of 87 characters, squiggles based on the letter “E,” arranged in three rows:

Again, every first-year student knew this one. It was the secret message sent by the famous composer, Sir Edward Elgar, to his inamorata, Miss Dora Penny-“Dorabella”-one of the recipients of a dedication in the great Enigma Variations for orchestra. This one was tough, because most cryptographers were not musicians and most musicians were not cryptographers, although come to think of it their disciplines had a lot in common, since each was based on writing in a language that bore no resemblance to the meaning, except by fiat.

But the Enigma Variations were tricky, even by musical standards. Elgar had composed a series of variations on a theme that, he claimed, was never actually heard in the piece itself. That is to say, the “theme”-angular and descriptive, which led some to suggest that it was nothing more than the topographic outlines of the Malvern Hills that Elgar knew so well, expressed in music-was only the counterpoint to the Unheard Melody. Scholars had spent most of the last century trying to identify the hidden tune.

Well, Major Atwater was no musician, so he didn’t much care about the mysterious melody. What he had in front of him, the famous “Dorabella” set of squiggles, was much more interesting.

For a century, amateurs and professionals alike had been trying to break the code, mostly in expectation of discovering some Victorian-Edwardian raciness secreted within, like one of the “snuggeries” that so feverishly occupied the Victorian pornographic imagination. And that the fact that Elgar had further memorialized Ms. Penny in the great orchestral work itself indicated that his affection for her ran very deep. “These are deep waters indeed, Watson,” as Sherlock Holmes famously said in some adventure or another. Despite the fact that a very high percentage of intelligence professionals were Sherlock Holmes fans, Major Atwater had never quite managed to see the charm of a world in which it was always 1895.

And then there was “Masterman XX.”

Work backward. Whoever assembled these ciphers had meant for that to be the punch line. It had to have some meaning. The reference was obvious-the famous “Double-Cross System” developed by the British during World War II. It was essentially a method of doubling captured German agents, returning them home, and then using them to spread disinformation. The XX stood both for the double-cross itself and for the Committee of Twenty, which oversaw the operations. Crude by contemporary standards of HUMINT tradecraft, to be sure, but there was always a first time for everything, and after the war, as the Allies split apart to become antagonists, it became the template for every doubled and re-doubled agent, every disinformation and false-flag operation that the American and the Soviets ran against each other.

He ran his hands through his hair. Already, it was thinning, he had to admit that. Life just wasn’t fair. Time to think this through again.

A series of ciphers, each one famous. Some easily solved, like the substitution ciphers, and others the object of countless efforts to crack them by amateur and professional alike. What was the common thread?

There wasn’t any. Literary references, imaginary ciphers, real ciphers, love-letter ciphers…what were the common themes?

Love and money, unless you counted the double-cross. But weren’t double-crosses always about either love or money? He felt like he was living in some kind of wacky film noir, a modern-day Philip Marlowe transplanted to suburban Washington, but with exactly zero chance of a hot blonde walking through the door with a big problem and a little piece of money.

Hang on. Follow your own damn logic. Think. That’s what they pay you do.

No, not just think. Associate. That’s what code-makers did, and it was up to him to reverse-engineer the damn thing, like the Japanese after World War II, trying to figure out how Western technology worked, and how they could do it better.

A code consisted not only of the actual cipher itself, but the overall concept behind it. In the Beale cipher, for example, the clues to the location of the buried treasure were hidden behind the referential numbers, but the real key was the Declaration, which obviously meant something to the code-maker. This is where it got tricky.

The Declaration might have had a primal, emotional resonance for the man calling himself Thomas Jefferson Beale-his very name would suggest that-but it also might, might be totally coincidental. His real name might not have been Thomas Jefferson Beale, and the use of the Jefferson ’s great call to arms might simply have reflected its ubiquity in American culture at that time. Correlation is not causation.

But, like master bomb-makers, master code-makers saw their work as a higher calling, an art form so special that they could not resist leaving some clue to their identity, or to the code’s purpose. Like the medieval artisans who would sneak signatures onto their work, in the hopes of living forever in stone or wood, the code-writers each had a style that spoke to their purpose. This is why I am doing this was, at root, the code behind every code, and if the applause came decades or centuries down the road, then so be it.

So why was he doing this?

Love and money. Money and love. That the code-writer was a man was a safe assumption. Most code-writers were men, and even if it was politically incorrect, it was a safe assumption that a woman had not sent these missives to Seelye-or, if she had, she was merely a courier. Men loved numbers, codes, statistics, hidden meanings, conspiracy theories. Not every man, of course, nor was every woman automatically ruled out as a participant. But every now and then you just had to play the odds, and the hell with the feelings of some female professor at Harvard.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Early Warning»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Early Warning» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Early Warning» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.