Vincent Zandri

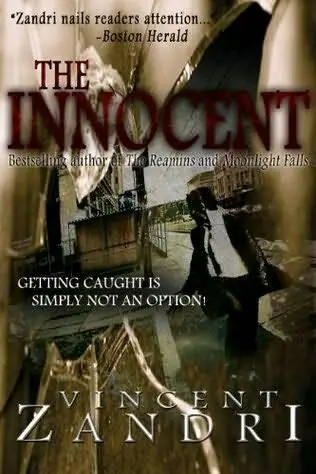

The Innocent

Copyright © 1999

Story goes, Vincent Zandri-prominent photo-journalist and globe-trotter-stumbled backwards into the story for this book, back in the nineties. He was working on the memoirs of some guy used to work as a prison guard at Sing Sing or Alcatraz or some such, when the basic premise of the novel As Catch Can came to him.

I don’t know if he ever wrote those memoirs. But in ‘99, As Catch Can was published and got all the accolades that a young writer always hopes for: it sold pretty well, the critics dug it, and there was even some vague stirrings of interest from the Cash Cow we call Hollywood. Riding on the success of As Catch Can, Zandri wrote another two novels and was well on his way to establishing himself as a major name in hardboiled fiction circles.

Then something happened, I dunno what. He dropped out. Some say Zandri-who, remember, is a sort of world-travelin’ action man type-was forced on the lam after seducing the wife of a prominent South-East Asian warlord. Some people were convinced he’d been murdered by a drug cartel after discovering a secret connection between them and the C.I.A. Others still were certain that Zandri had finally fallen into the bottle and was strapped up in some padded room in his hometown of Albany.

Thing is, no one really knew what happened.

Thing is, nothing happened.

Zandri had only been recharging, and re-acclimating himself to the new world of publishing. While he’d been away, working the day job as a picture-snapping super-hero, the industry had changed dramatically and even someone with as remarkable a track record as our hero had his work cut out for him getting a new book on the stands.

So he went to the small press, with his novel Moonlight Falls.

Out of necessity, Vin is a relentless self-promoter. By the sweat of his brow he made sure readers and critics noticed Moonlight Falls and his hard work paid off-Falls actually sold remarkably well for a small press release and was reviewed favorably all over the place. His next small press novel, The Remains, was even better and showed off Vin’s diversity and lean style beautifully.

I’ve told you all that to tell you this: The novel you hold in your hands (or on your Kindle, or whatever) is really As Catch Can, just with a new title and a fancy new cover. Our hero has come full circle, you could say. And I kinda envy you, about to read this book for the first time. It has all the wild enthusiasm of a young writer’s first crack at the genre, and it’s tough-minded and lyrical and unforgettable.

And, as a new starting place for Vincent Zandri, it’s more than a little symbolic. Vin has lots more stories in his head, and this “touching base” with his origins, I suspect, is just a prelude to even more great work.

Heath Lowrance, noir critic and author of The Bastard Hand

Detroit, MI

September 4, 2010

Stone walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage; Minds innocent and quiet take

That for an hermitage. If I have my freedom in my love,

And in my soul am free, Angels alone, that soar above,

Enjoy such liberty.

– RICHARD LOVELACE, 1649

BOOK ONE. GREEN HAVEN PRISON

Statement given by Robert Logan, the senior corrections officer in charge of the transportation of convicted cop-killer Eduard Vasquez at the time of his escape:

You wanna know about Vasquez, well I’ll tell you about Vasquez. He looked like death twisted inside out. That dentist did a real job on him, or so I thought at the time. What I didn’t know was that Vasquez was one hell of a faker, one hell of an actor. You should have seen him sitting in the backseat of that station wagon all bound up in shackles and cuffs-skin white, lips swelled, gauze stuffed inside his cheeks. Blood and spit were running down his chin. His eyes were glazed and puffed up. That toothache must have been a real headache now that A. J. Royale, the butcher of Newburgh, had gotten to him. No way could Vasquez escape. But then how could I make any sense out of the feeling I’d had since we’d started out? The feeling that told me he was going to make the break?

But here’s how it really happened:

My partner, Bernie Mastriano, he drove the station wagon while I adjusted the rearview mirror to just the right angle so I could get a better look at Vasquez in the backseat without turning every ten seconds. He was sucking air like there’s no tomorrow. His feet and hands were bound up and he was locked up in that cage and you could see the pain all over his face. He just put his head back on the seat, opened his mouth wide, let his tongue hang out like a sick puppy. He didn’t seem so tough then. Seemed kind of stupid and pathetic, not at all like the crazy psycho who pumped three caps into the back of that rookie cop’s head back in ‘88. Vasquez kept suckin’ up that air like it somehow relieved the pain from the hole Royale left in his mouth. Then out of nowhere he doubled over, threw his head between his legs, started heaving blood all over the floor.

Mastriano screamed, “I think he’s having a freakin’ heart attack.”

I told him to shut up, stop the car.

“Heart! Attack!” he screamed.

“Damn it, Bernie,” I said, “pull the car over before somebody gets hurt.” Sometimes you gotta pound things into Mastriano’s head. He pulled the wagon onto the shoulder of Route 84, killed the engine. Then he pulled Vasquez out of the car and laid him out on the field next to the road.

I was right behind him.

When I got down on my knees to see if Vasquez had swallowed his tongue, the black van pulled up behind the station wagon. The back doors of the van swung open. There they were. Three of the hugest dudes you ever saw in black ski masks, packing sawed-off shotguns.

Mastriano went for his sidearm. But he took a shot in the head with the butt end of a shotgun, hit the ground cold. I got up and went after the son-of-a-bitch. I guess I didn’t see it coming either. I went down, right next to Vasquez. They kicked me in the face, in the forehead. See that purple-and-black welt above my eye?

One of those masked bastards knelt down, reached into my pockets, felt around for the keys to Vasquez’s handcuffs and ankle shackles. But here’s what really got to me: When Vasquez was free, he jumped up. When those shackles were off, he spun around to his knees, got up, spit out that bloody gauze, let out a laugh. “Hey boss,” he said, you fell for the whole thing, hook, line, and sinker. Just like that, boss.”

I rolled over onto my side in the high grass, jammed my knees into my chest. I couldn’t work up the air to talk. But my ears were still good.

“Lock ‘em up,” Vasquez said.

They cuffed Mastriano and me together with my own handcuffs, shoved us into the front seat of the wagon. Vasquez ordered one of his men to take the wheel. But before we pulled away, he leaned his head inside the open window.

“No hard feelings, boss. Hope this don’t screw up the promotion.”

The last thing I remembered before waking up at the gravel pit was Mastriano’s piece coming down hard on my head.

1997 WAS THE YEAR Green Haven Prison went insane. The winter hadn’t produced a single snowstorm that lasted for more than an hour before turning to rain and slush, and what should have been covered with a velvety-smooth blanket of white went on being gray and lifeless and pitiful, as if God Himself saw to it that the twenty-five hundred inmates and corrections officers living and working inside nine concrete cell blocks never once forgot where they were and why they were put there in the first place.

Читать дальше