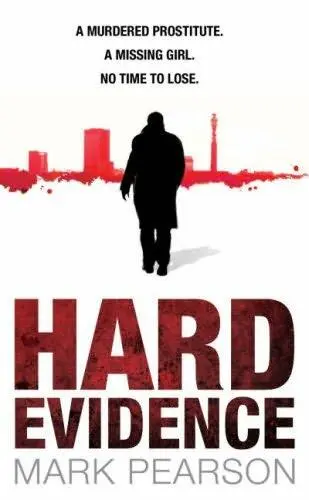

Mark Pearson

Hard Evidence

Copyright © Mark Pearson 2008

In 2004/2005 police figures indicated there had been 1,028 child abductions in England and Wales. That's three children a day. Or night. Abducted. Every eight hours a child is stolen in the UK.

BT press release

Each year in the UK more than 40,000 children under the age of 16 are reported missing – and after two weeks 1,300 children will still not have returned home.

BT Media Centre

Night-time on the river, twenty-five miles west of London. Kevin Norrell, a foul-breathed and acne-scarred man, hooded and sweating, pulled hard on the oars, really getting into it now. Years of steroid abuse had given him strength, if not wisdom, and his blades flashed across the dark ridges of the windblown river like scalpels slicing through mercury. He grunted as they dipped into the water and pulled the boat upwards and forward. In the cloudless sky above, the moon hung full and fat, the sickly colour of a dying man. The colour of Billy Martin's yellowing face, in fact, as he lay huddled in the corner of the small skiff. His hands were bound with twisted coat-hanger wire, his mouth was pulled into a painful rictus by a gag made from his own shirt. Trembling, he pulled his legs protectively in towards himself.

'For God's sake keep still!' A hooded man at the other end of the boat, holding a video camera.

Kevin Norrell pulled unconcerned on the oars, not missing a beat. He didn't know or care who the huddled man was; he was paid for his muscle, not his brains. Billy Martin cared about something, though. You could see it in his rat-like eyes as they flicked from side to side like a warning finger.

'Never work with bloody amateurs.' The hooded man with the camera again. 'This isn't a steadicam, you know.'

Billy Martin twisted his face and managed to move the gag a little. 'You think you're scaring me? You're not. Who do you think you're dealing with here?'

'With you, dear boy. We're dealing with you. We're washing you away. Like a blot, like a stain.'

'I've got insurance.'

'You had insurance. I'm afraid the policy has recently been cancelled.' He nodded to Kevin Norrell, who reluctantly laid down his oars and gripped Billy Martin's shoulders. Martin tried to shake loose, but Norrell's muscles bunched and his fingers dug into the struggling man's shoulders like mechanical claws and held him powerless.

'You can't do this.'

'But we can,' said the hooded man; he pointed the camera and nodded encouragingly. 'Good. Let's see the fear.'

Kevin pulled Billy Martin upright; he was screaming with pure terror now, desperately trying to escape the huge man's grip. But Kevin lifted him up, his feet twisting uselessly in the air, then threw him into the river as easily as passing a basketball and with the casual indifference of a refuse collector emptying a dustbin.

Billy Martin's scream rang in the night air like a steam alarm as he crashed into the cold water, his arms burning as he strained against the wire holding him, desperately trying to stay afloat, and failing.

The second man nodded again, zooming in for a tight shot as the rocking boat steadied itself, and called out encouragement to Billy Martin.

'That's it. Wriggle like an eel, splash out with your legs.'

Billy Martin's screams gurgled and faded as he sank beneath the water. The ripples gradually died away, the boat was still and the river was peaceful once more. The cameraman nodded to the rower, as if to praise a child, but the smile didn't reach his eyes. Eyes which were as cold as the water that had suddenly filled Billy Martin's lungs.

'Shame we couldn't get crocodiles,' he said after a moment.

If Kevin Norrell had any idea what the man was talking about, it certainly didn't register on his face.

The football. The cricket. The state of English sport in general. The bird off Emmerdale getting her tits out for some lads' magazine. They'd banned smoking, they'd be banning alcohol in pubs next, something else to thank the Californians for, no doubt, like the Atkins diet and low-carb beer, and the bloody Mormons who banged on your door with the sincerity and charm of house-to-house insurance salesmen, or cockroaches.

Jack Delaney let the conversation wash over him as he downed a shot of whiskey with a quick, practised flick of his wrist.

He was sitting on a cracked leather stool at the wooden counter of the Roebuck, a scruffy north London pub. A big mirror behind the bar, with thirty-odd bottles of spirit in front, bouncing different-coloured lights off it like a Christmas tree for alcoholics.

Delaney picked up his pint glass and let a sip of creamy Guinness soothe his throat if not his soul; even the door-to-door Mormons couldn't sell him that, even if he had been in the market. No new soul for Jack Delaney today; just the old, sin-spotted black thing at the heart of him. Forgive him, Father, for he had sinned. If women looked at him, which they did often, they'd try to guess his age and reckon it to be around the late thirties. He had dark hair, dark eyes, and if they got to know him they would get to see that dark soul. Mostly he didn't let them get to know him.

Delaney held his whiskey glass out and nodded with a wink at the barmaid. 'Evaporation.'

The barmaid took his glass, smiling but with no real hope behind it. She poured a generous shot of Bushmills and placed it in front of him.

'Cheers, Tricia.'

'Any chance of getting a drink here!' A large man, a few inches over Delaney's six one, but carrying weight, and drunk. Delaney gave him a glance, dismissed him and returned to the solace of his Guinness.

'The fuck you looking at?'

'Minding my own business here.'

'You seem to be minding my fucking business. And you' – to the barmaid – 'get me a fucking lager.'

Delaney sighed and flashed her a sympathetic smile.

'Sorry about this.'

The big man's eyes widened; he shook his head, disbelieving.

'You got a problem or something, you fucking Irish fucker?'

Delaney debated discussing the delicate beauty of the English language, but instead stood up from his stool, picked up an empty bottle and smashed it against the bar. Then kicked hard, very hard, with the side of his foot into the larger man's knee. The man grunted with surprise and blinked. He swayed back, and Delaney flashed his left hand on to his throat, grabbing his windpipe and holding him rigid. Then he moved the jagged edge of the broken bottle towards the drunken man's now terrified eyes.

'If you wanted to dance, you should have asked nicer.'

'Please.'

'Too late for please.'

Delaney's hand tightened on the bottle, his hard eyes telling the fat man the really horrible nature of his mistake.

A hand tapped Delaney's shoulder and he turned round to see a smiling man in his thirties. Dirty-blond hair, brown eyes, five ten. He clearly worked out, the muscles tensing in his arms as he balanced on the balls of his feet like a boxer, ready to move.

'Let him go.'

The man dipped a hand into his smart leather jacket and fished out his warrant card, which he showed round the room like a warning. Nobody paid him much attention; a fight in the Roebuck was as unusual a sight as a G string in a pole-dancing club.

'Police. Detective Sergeant Bonner. Why don't we all calm it down?'

Those who had been watching turned back to their beers, losing interest.

Delaney stepped back and put the broken bottle on the bar. Bonner leaned in to the shell-shocked drunk, who had fallen to his knees and wet himself.

Читать дальше