‘What’s it called?’

‘The lichen? To tell you the truth, I don’t know. Whatever it was, it’s no longer there. The trunk has a nice shaggy jacket of opegrapha corticola , but among the lichens that’s about as rare as the cabbage white butterfly.’

‘So the conservation didn’t work?’

‘Apparently not.’

‘Will it reappear?’

‘I wouldn’t hold your breath.’

‘Could someone have misidentified it?’

He rolled his eyes. ‘I can’t answer that, not having been here at the time.’

‘The others aren’t experts like you.’

‘In their own spheres they are. The major with his military know-how keeps a special eye on the war games.’

‘And the golf.’

‘Yes, indeed, along with Sir Colin, who is a man of the turf and has the racecourse under his wing. Augusta White is our legal eagle. And if Augusta represents law, your esteemed Georgina is the embodiment of order.’

‘None of them wildlifers.’

‘That’s my section of expertise, apart from the obvious.’

‘They’re fortunate to have you. Was the previous vicar a botanist?’

‘Arthur Underhill? No, he was a literary man, a Beckford expert, so he was in his element living here. Beckford wrote books, you know, as well as building towers.’

‘Should I have read any?’

‘I doubt if they’ll assist your investigation. He wrote much about his travels abroad. His novel, called Vathek - in French, would you believe? – was set in some Arab country, and he also wrote a peculiar book called Biographical Memoirs of Extraordinary Painters, a literary folly, you might say, because none of the painters existed.’

Diamond was losing control of this interview. He’d only asked about Arthur Underhill.

‘Beckford is still a cult figure,’ the vicar went on. ‘People knock on my door asking the way to the tower and some of them know a lot about him. You still get the occasional crank who thinks he squirreled away some of the treasures and masterpieces he stacked in the tower. The auction after his death was a very dubious affair presided over by a crooked auctioneer and his son who absconded soon after.’

‘I don’t know why Lansdown should give rise to so much crime,’ Diamond said. ‘It’s just one large hill, after all.’

‘It’s Bath’s back room,’ Charlie Smart said, ‘stuffed with things people want to forget about.’

‘Where’s Ingeborg?’ he asked in the incident room.

Septimus looked up from his computer. ‘Somewhere on Lansdown by now, looking for an elderly warhorse. I told her your theory and she got really fired up.’

John Leaman said, ‘Any excuse to get out of this place.’

‘Wishing you’d thought of it?’ Diamond said.

‘I’m not a horse person.’

‘Who’s the old nag in here, then?’

There were grins around the room.

Septimus added, ‘She was on the phone to someone in the Sealed Knot, finding out where they stable the horses they use.’

‘What’s she going to do if she finds the right one – interview it?’ Leaman asked, not done for yet.

‘I expect she’ll get a hair sample.’

‘To see if it’s the same colour?’

‘For the DNA,’ Diamond said, using his freshly acquired knowledge. ‘Didn’t you know horses have DNA?’

Leaman went quiet.

‘Plenty of horses are taken to Lansdown for the race meetings,’ Paul Gilbert said with a charged tone in his voice. He’d been on a high since finding Nadia’s landlady. ‘Maybe we should make a check up there.’

‘Twenty-year-olds, in training?’ Diamond said.

He turned a shade more pink. ‘I guess not.’

But something was stirring in Diamond’s memory. He asked, ‘What happened to that calendar Ingeborg made of events that happened on Lansdown? It was on the display board.’

‘She transferred it to a computer file, sir,’ one of the civilian staff said. ‘Would you like to access it?’

‘I would if you do it for me.’

‘On your computer, or mine?’

‘On your

‘Mine.’

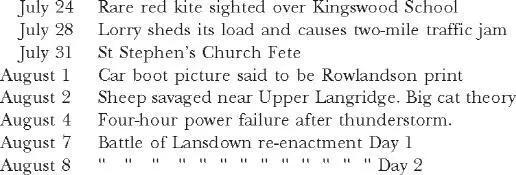

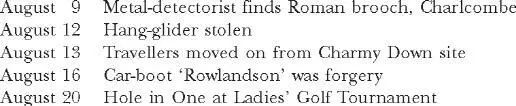

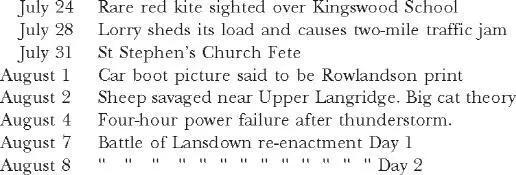

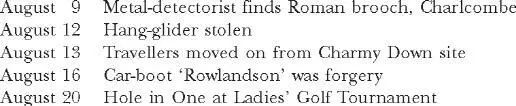

In the quiet of his office, he scrolled through Ingeborg’s listings, most of them commonplace and trivial. Her mind-numbing task had been done at Keith Halliwell’s suggestion and at the time Diamond had thought it a monumental waste of effort, but had refrained from saying so. What possible relevance could club reunions and cross-country races have to a murder enquiry? Now that the time frame had narrowed to a few days in the summer of 1993 – from Nadia’s arrival late in July to the battle re-enactment on August 7th and 8th – the calendar was worth a look.

She had definitely arrived after Mrs Jarvie’s eightieth on July 23rd. He watched the pages roll like film credits and stopped them at the end of July, 1993.

Disappointing. A few suggestions of summer, but nothing to link to Nadia except the re-enactment – and that was only because she’d been buried close to where the fighting took place As for the rest, rare birds and big cats were staple items for newspapers in the so-called silly season. A traffic jam and a power failure didn’t spark the vague recollection he thought he had of something significant.

He scrolled on a little.

He couldn’t imagine Nadia metal-detecting or hang-gliding or golfing like some leisured Bathonian. She’d be trying to get work. Yet he had a sense that the information on the screen mattered to the case. Elusive thoughts were trying to connect in his brain. He scrolled back and started to study the list again, from the red kite onwards.

His phone beeped.

Wigfull’s voice. ‘Just to let you know that your Ukrainian girl is in tonight’s Bath Chronicle. I’ve got an early copy if you want to see it. And the story will be on Points West and HTV News tonight, so the phones should start ringing soon. You’d better not go home early.’

His train of thought had derailed. ‘Nice work, John. Do you want to be part of the excitement?’

‘No, thanks. It’s my positive thinking night.’

He didn’t ask.

He took one more look at the screen before stepping into the incident room to see who was willing to do overtime. The practi-calities of managing a team had to be gone through. Paul Gilbert was game and so were a couple of the Bristol team and three civilians. Not Septimus: he’d worked more than his share of late evenings in recent days and wanted a night off.

‘Fair enough. We’ll cope,’ Diamond said.

A high profile appeal to the public always brings in responses. Most are made in good faith, even if a high proportion prove to be mistaken. Wanting to help is a human instinct. Sometimes the offers are driven more by the wish than the reality. It’s easy to convince oneself that certain events took place and fit the facts of the appeal, particularly after a long lapse of time. Additionally there are callers not so altruistic, who see an opportunity of profit. They’ll have heard about payments to informants. Usually their information is worthless. Finally there are the nuisance callers, the equivalent of the idiots who make bogus 999 calls.

Out of all this the police must sift the genuine witnesses. Diamond went over the procedure with his volunteers, stressing the known facts about Nadia: that she was Ukrainian, under twenty, a Roman Catholic, had lived for a time in London as a prostitute and was in lodgings in Lower Swainswick. She spoke good English, had been orphaned, so had no family, and she would have been wearing jeans and a T-shirt. ‘The trick is that you don’t give out any of this. You listen to the information coming in and see if it checks. Be sure to get the contact details of the informant before they tell you their story.’

Читать дальше