Humphrey Hawksley

MAN ON ICE

To all families and nations divided by politics

THE FOLLOWING TAKES PLACE IN THE TWO DAYS BEFORE THE AMERICAN PRESIDENTIAL INAUGURATION ON JANUARY 20th

Little Diomede, Alaska, USA

Thick mist hung over the frozen Bering Sea and inside the helicopter cabin a familiar voice broke through the static of Rake Ozenna’s headset. ‘We have an emergency evacuation,’ said his adoptive father, in a tone that was calm but edged with urgency. ‘How far out are you?’

‘On the ground in about five minutes, Henry,’ said the pilot.

Rake’s fiancée unwrapped her arm from his shoulder and pressed the talk button on her headset cable. ‘This is Dr Carrie Walker,’ she said. ‘I’m with Rake Ozenna. I’m a trauma surgeon. What exactly is the patient’s condition?’

A woman’s voice answered. ‘This is Joan, district nurse. Akna’s waters have broken.’

Joan was Henry’s wife. Rake had told Carrie about them and his home island many times. Even so, he had been apprehensive about bringing her here and the past minute was proving him right. He tried to catch her eye, but she was concentrating, at work a hundred percent on her new patient. ‘Thank you, Joan,’ she said. ‘Do you know how many weeks into the pregnancy?’

‘We think thirty-five weeks.’

‘And how old is she?’

‘Fifteen.’

Carrie showed no reaction to the young age. She had seen far worse, so had Rake. She snapped open her bag to check her medicines. ‘Does she have a fever?’

‘A hundred and two.’

‘Thank you. Keep Akna comfortable—’

The pilot cut in. ‘We’re three minutes out. Henry, I need you on the helipad. The wind is everywhere.’

Carrie tapped her finger across packets of antibiotics and said confidently, ‘Reassure Akna that help is on the way. We’ll get her safely to hospital in Nome in a couple of hours.’

Rake wasn’t so sure, but he stayed quiet. It depended on exactly where Akna was. It could take half an hour to get her stretchered safely down to the helipad. In January, this far north, the sun barely broke above the horizon. Its dim light merged with the moon and stars to create a glow of daytime winter darkness, and now it was coming up to midday, but it could have been midnight. The way clouds were scudding meant frozen fog could move in at any time.

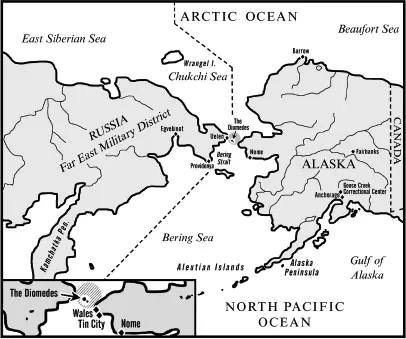

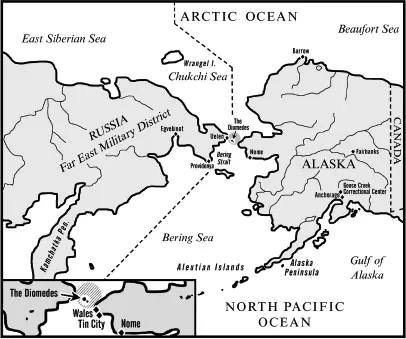

An hour earlier they had left Nome to fly over a flat white Alaskan emptiness until fog almost forced them to turn back. The pilot managed to climb above it and for a long time they could only see the top of a shimmering low cloud bank. When they descended again, two islands appeared, solid and dark, like guards keeping vigil on the ice-covered expanse. Rake pointed to the longer, flatter island on their left. ‘That’s Big Diomede,’ he said to Carrie, tapping the window. ‘They call it Ratmonova. See, along the top, Russian military observation posts.’

‘Oh, my God!’ Carrie looked in fascination and turned to see out the other side. ‘And you grew up over there?’

The helicopter shook as the pilot turned them into the wind at a mid-point between the islands, exactly where Russia and America met. The international dateline ran along the sea border. A few meters to their west, and they would drift into another day and another country.

As the smaller island on their right became more visible, Carrie hooked back her blonde hair and cupped her hand against the window. Light from outside the helicopter silhouetted her strong face, high cheekbones, and prominent jaw. An orange windsock on the helipad gave a splash of color against the grayness of the settlement, a pallid cluster of small buildings, dwarfed by the steep island hillside rising directly behind.

Carrie’s home could not have been more different to his. She was half Estonian, half Russian, and was raised as a Brooklyn Catholic, from a family of successful doctors. He was a native Eskimo from the Diomede Islands, which lay at the very edge of American territory and where ‘family’ held a looser meaning. Her father was a top cardiologist, her mother a gynecologist, and Carrie became a trauma surgeon. Rake had no idea where his mother or father were, could barely remember their faces. He had been raised by Joan and Henry Ahkvaluk, his father’s cousins. As soon as Rake was old enough, he had joined the Alaska Army National Guard. From the lowest rank of private, he broke through to reach captain in the 207th Infantry Group based at Fort Richardson outside of Anchorage, better known as the elite unit of Eskimo Scouts, perfect for deployment to mountain winters in Afghanistan, which was where a sensible girl from Brooklyn fell in love with a wild boy from the Diomedes, at least that was how they told it to friends. Carrie and Rake met over a car bomb in Kabul.

It was more than ten years since Rake’s last visit to Little Diomede. Jumbled images came to him of this place he knew so well and wished he could understand. Since then there had been Iraq, Afghanistan, the Philippines, Iraq again, Afghanistan again. And now he had Carrie, who had settled him.

Drab clapboard homes stood on layers of walkways, one above the other, up the steep slope. The helipad, a rough concrete square, jutted out from a coastline of huge boulders. To the left stood Rake’s old school, its green walls and snow-covered roof shimmering under clear moonlight. Three steel dinghy boats were pulled up on the iced shingle of a tiny bay. Rake spotted the one belonging to Henry. In front, half a dozen snowmobiles stood on the sea ice and further along was the old, abandoned one, that Rake had ridden the night a polar bear had threatened the village. In the wildlife magazines, polar bears were made to look majestic. Close up, they were dirty, dangerous, eating machines. Henry rode out on the snowmobile with his two surrogate sons, Rake and Don Ondola, and showed them how to track and kill the animal. That morning, the whole village had walked across the ice to carve off meat and store it for winter. Don got the hide because he was two years older. He had been like a brother to Rake. But now he had gone mad was serving time for murder, which was why the emergency radio call was so troubling. Akna was his daughter.

Carrie knew some of this, but not all. Rake had told her about the hunting of walrus, seal, and polar bear; the isolation, the winter darkness, the summer light; how the Eskimos had lost their language because the school only taught in English; how men away hunting had asked friends to look after their wives in their own beds in a practice called wife-sharing which is why Eskimos weren’t so good at doing the mom, pop, and three kids nuclear-family thing; how missionaries had tried to change them but without much success, and had given up and were now gone from the island. That had made Carrie laugh.

He told her about the sacred ancestral graves on the hillside and how he could read the weather by the way the birds flew around the island. Carrie loved all that, but she was no fool. She would figure out the whole picture for herself once they got there. He hadn’t reckoned on her starting even before they landed.

From the helicopter window, he saw Henry step out from a hut next to the old wooden church on a higher walkway. It used to be Don’s house. Rake didn’t know who lived there now. Henry was more than sixty years old, but skilled with his boots on the ice, faster than many men half his age. He started down the walkway to meet them.

Читать дальше