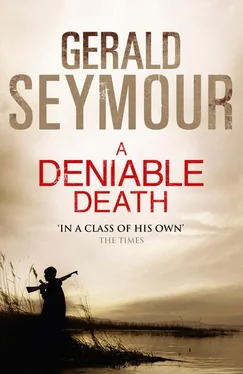

Gerald Seymour - A Deniable Death

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gerald Seymour - A Deniable Death» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Deniable Death

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Deniable Death: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Deniable Death»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Deniable Death — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Deniable Death», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Out in front, moving easily and light-footed, was Badger. The American and the foreigner kept pace with him. Foxy felt the rotors’ pressure blasting him from behind and staggered as the beast, anonymous and black, rose again and headed back over the bay. Gibbons was beside him.

‘Why this place?’ Foxy might have nudged a hint of sarcasm into his tone. The outside of the edifice seemed to drip water from roof gullies and guttering, and he expected that half as much again would be falling through the ceilings into the salons and bedrooms. He held tightly to his bag and thanked the Lord he always packed more socks, smalls and shirts than he anticipated needing. All of them had overnight bags except Badger, who likely stank and would be higher by the evening.

‘Not down to me. He who pays the piper calls the tune – know what I mean?’

He blinked in the rain. ‘I don’t.’

‘All in good time, Foxy – if you don’t mind the familiarity. It’s always best if names are in short supply. Our esteemed colleague from the Agency is paying the piper. The Americans are doing the logistics, which means their bucket of dollars is deeper than our biscuit tin of sterling. It’s the sort of place that appeals to them.’

‘And people live here – survive here?’

‘There is a life form in the Inner Hebrides that probably needs to huddle for comfort in the kitchen. I’m assured we won’t be disturbed by the family. Truth is, for this one the piper needs quite a bit of paying because it’s not the sort of thing – Monday through Friday – we usually do. Let’s get out of this bloody weather.’

They went in through the high double doors, but no warmth greeted them. Foxy had good eyes and a good memory, and his power of observation in poor light was excellent: he noted the washing-up bowl in the centre of the tiled floor, the portrait of a villainous-looking kilted warrior above the first bend in the stairs, the faded pattern on the couch, that the paint was off all the doors, the smell of dogs and overcooked vegetables, an older man in earnest conversation with the American and a woman with bent shoulders, a thick sweater and a bob of silver hair. The rain beat on the door behind them, water dripped into the washing-up bowl and Badger sat on the bottom stair, showing no interest in anything around him. Foxy noted all of it.

The voice of the greeter was soft in his ear: ‘Their grandson was Scots Guards in Iraq, attached to Special Forces, didn’t survive the tour. They’d want to help and, as I said, the Americans have a deep bucket. Improvised explosive device, on the al-Kut road. You’re going to hear a bit about improvised explosive devices, but I’m getting ahead of myself.’

Foxy said vacuously, ‘I have some experience, but this should be interesting…’

The man laughed without mirth, and Foxy couldn’t see what had been funny about his remark – about anything to do with improvised explosive devices.

When the Engineer worked in his laboratory, or was on the factory floor checking the craftsmanship of the machine-tool work, he could escape from the enormity of the crisis that had settled on him. It was like the snowclouds that built up over the mountains beyond Tehran when winter came. When he played with the children he could briefly think himself free. When he walked on the track in front of his home and watched the birds hovering, swirling and wafting, there were moments when the load seemed to slip away. When he was at his bench, working on the use of more ceramic material to replace metal parts and negate the majority of the portable detectors… When he was out on the long straight tracks that had been bulldozed beyond the camp into wilderness and studied the capability of his radio messages to beat the electronics deployed against him, he sometimes forgot… The moments never lasted. There was laughter, rarely, and there were smiles, sometimes, and there were those times that the work was successful beyond dreams – counter-measures failed, detonation was precise and a target was destroyed in testing – but every time the cloud formed again, and the pleasure of achievement was wiped out. He could see the ever-growing weakness in his wife, the depth of her tiredness, and could watch the bravery with which she put on a show of normality. She was dying, and the process would each day be faster, the end nearer.

He could not acknowledge it to her, but he realised his fingers were clumsier and his thoughts more muddled. He suffered. He couldn’t picture a future if – when – she was taken. Only once had he called in the debts owed him by the revolution of 1979 when the Ayatollah had left Paris and flown back to his people. He had been nine years old and had watched the television with his father, who taught mathematics in Susangerd, as the Imam Khomeini had come slowly down the aircraft’s steps.

He had been three years older, and had wept when his father had dragged him back into their home: he had been about to join the child volunteers who would be given the ‘key to Paradise’ in exchange for clearing the minefields laid by the Iraqi enemy, making safe passage for the Revolutionary Guard Corps and the Basij militia. His father had locked him into a room and not permitted him to leave the house for a week. He had gone back to school and there had been many empty places in the classroom. It had been said that when they had ran across mined ground they were killed by the explosions, their body parts scattered, that rats and foxes had come to eat pieces of their flesh. It had also been said that on the third day of the clearance operation the children, his friends from school, had been told to wrap themselves in rugs and roll across the dirt so that their bodies stayed together, were easier to collect after the line had moved forward.

He resented not having a plastic key to Paradise. He did not believe the lie of foreigners that a half-million had been imported, at a discount rate for bulk, from a Taiwan factory.

He had been twenty-two years old, a second-year student of electronic engineering at the Shahid Chamran University in Ahvaz, when his father had died. The martyr Mostafa Chamran, educated in the United States and with a PhD in electrical engineering, had fallen on the front line and was revered as a leader and a fighter. There had been many around him to whom Rashid could look for inspiration, living and dead. He was the regime’s child and its servant, and he had gone where he was directed, to university in Europe and to the camps in his country where his talents could be most useful on workbenches. This once he had called in the debt.

In the afternoon he would be on the road that led away from Ahvaz towards Behbahan. A new shipment of American-made dual-tone multi-frequency equipment had come via the round-about route of Kuala Lumpur, then Jakarta, and he would test it for long-distance detonations. The Americans, almost, had gone from Iraq, but it was the Engineer’s duty to prepare the devices that would destroy any military advance into Iran by their troops. He would be late home, but her mother was there – the message had come by courier the evening before.

Neither he nor his wife ever used a mobile telephone. In fact, the Engineer never spoke on any telephone. No voice trace of Rashid Armajan existed. Others communicated for him from his workshop, and he used encrypted email links. Messages of importance were brought by courier from the al-Quds Brigade garrison camp outside Ahvaz. One had come the previous evening.

He and Naghmeh should be prepared to leave within the week. Final arrangements were being confirmed. He was not forgotten, was honoured. The state and the revolution recognised him. At his workbench, out of sight of others, he prayed in gratitude. Was there anything another doctor, a superior consultant, could offer? Would a long journey weaken her further and bring on the end? But the courier had brought a message that gave hope. He saw death on Internet screens and from recordings on mobile phones. The killings were caused by his own skills. He lost no sleep over that knowledge, but had not slept well since the Tehran doctors’ verdict when he had seen the bleakness in their eyes. Now hope, small, existed.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Deniable Death»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Deniable Death» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Deniable Death» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.