When you read Bernal Díaz’s book about the conquest, you get the impression that Mexico City is built upon a lake, with little barges plying between temples and wooden houses; it sounds beautiful, like Venice. I don’t know what happened to the lake, but when I was there, it was a nightmare of roads and concrete, insane traffic, poisoned air,

The driver was only passing through, but it took hours. At one point, in a nicer part I saw Americans at a café near a big church.

A man and a woman in shorts reading the International Herald Tribune . Americans, English words in a newspaper. I wanted to wind the window down and say something. Connect. But I did not. The light changed and we went on.

At a place called El Oro, the trucker stopped at a clothing factory. He asked around and we found a driver heading north.

Tall guy, chain-smoker, spoke a little English, wanted company. Said his name was Gabriel.

I told him mine was Michael, and he said that we were two of the archangels and that was good luck.

I shared his food and his little back sleeping cabin for two days. We talked fútbol and women and ate stale bread, and he told me long and complicated jokes that I couldn’t get but cracked him up.

María’s medicine was gone and the pain in my stump had become incredible. To help, Gabriel let me have some of his homemade moonshine, evil stuff that would have put hairs on the chest of the Lancôme girl.

In Chihuahua City, Gabriel said that we were at the parting of the ways. He was delivering shirts to California and had to turn west. I was going to New York City, and from here the Texas border was only about two hundred kilometers. Texas to New York was a much shorter journey than California to New York.

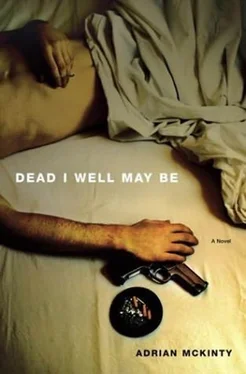

I could see what he was saying, but I wasn’t quite ready to leave him. It was safe here in this cab, with grain whiskey and old bread and my chatty fellow seraph. I wanted to get back, I had to get back. There was a scene to be played out, the handgun flaring, a knee jerking, the pain to be extracted, the terror to be inflicted, but not yet, not yet.

I’ll go with you all the way to the California border, I said.

He didn’t mind at all, and we drove west to Tijuana.

Tijuana, as most everyone knows, is a miserable place, and it was worse back then, but you only have to go to the nearest bar and be a little discreet before you can get hooked up with someone who can help you cross.

I was discreet, but I had no cash and I had to sponge off two American college guys in a VW bus. They’d been exploring Baja and surfing the Pacific side and had a lot of questions, and they bought me a beer, and I invented a story about myself that I’d been hitching around the Americas for the last few years, working and drifting and seeing things. They thought this very cool for a disabled guy and bought the whole shebang. My invention ran away with me a little, and I mentioned Colombia and Ecuador and the heights of Machu Picchu.

I explained to them I was going to have to cross illegally into the U.S. because I’d lost my passport months ago. They thought this was cool too, and offered to hide me in the bus, but I declined and said that that wasn’t the way things were done, and what I really needed was money.

They gave me fifty bucks and I thanked them and watched them drive off towards the massive customs station that led back into the United States.

With dough in hand and a grilling in a back kitchen that convinced two teenagers that I was not in the employ of the U.S. government, I was told that we were going that night.

A dozen of us met outside a bar off the strip and away from prying eyes. We waited for a long time and I thought I’d been ripped off, but eventually a van pulled up and we drove off into the desert for a while.

I had to climb a barbed-wire fence, which was tricky in my condition, but not impossible, and then there was a solid metal fence, which was a piece of cake and had handy grooves, as if designed for aiding wetbacks with dodgy legs.

I crossed somewhere east and south of San Diego with a score of other guys of all ages. We walked into no-man’s-land for some time and then a flashlight beam appeared which was either the agents of the Immigration and Naturalization Service or the boy we were supposed to meet.

Our boy. Young, short, black jeans, black denim jacket, and a black Stetson. He yelled at us as if we didn’t see him and we went over, me muttering that half the bloody state of California must have heard the eejit. A van idled nearby and everyone gave the driver money. I didn’t have any cash left now but they let me come along. They were good guys, and most of them were agricultural laborers who did this thing every year. Fruit-picking season was over, but in Las Vegas, building season was just beginning. We drove all night and into the next day and the final stop was an industrial complex just south of Las Vegas itself. Everyone was there to demolish and build hotels and with my experience I knew I could have been on to a good thing, and but for my leg I might have made a fortune. But as it was, no one was ever going to hire me, save to make the coffee, so I thanked the guys for the ride and started hitching again east.

I was on the road an hour and a half when a sheriff’s officer picked me up and told me that hitching here was against the law. I said I wasn’t aware of that and he recognized the accent and asked me what part of Ireland I was from. I said Belfast and Deputy Flinn said that his grandmother on his father’s side was from Belfast. I’m not the biggest fan of peelers or other agents of the law, but Flinn was a big, gingerbapped, pale-skinned, nice bloke who almost wept over my story, which was that I’d come to Vegas to work as a builder but a hoddropping accident had cost me my foot and since I was an illegal I couldn’t very well go to the authorities to get work comp. I was hitching my way back to New York, where I had an address of a distant relative in Brooklyn who might sport me the cash to carry me back broken and dispirited to the Old Country.

Well, Seamus, Flinn began (for I was called Seamus McBride in this little universe), that’s about the worst thing I ever heard, and I want to lend you some cash to get the Greyhound. No, don’t object. I know you guys are full of pride but I absolutely insist.

I did object and explained that I had got myself into this mess and would get myself out of it without having to rely on the well-meaning charity of strangers.

Flinn was not to be daunted and explained that this money was only to be a loan and I would pay him back. Surely it was foolishness not to accept a loan from a friend and wasn’t that what I was going to do in Brooklyn anyway? Since he put it that way, it was hard for me to refuse, so I took his name and address and I did pay the bugger back about a month or so later, when, incredibly, I was on Ramón’s payroll, wearing a thousand-dollar suit and carrying a bloody Uzi.

He gave me two hundred-dollar bills and left me with handshakes at the bus station in Las Vegas. I bought a ticket to New York and stayed on all the way to Denver, where I had to get out and stretch and get my wits together after a very long and unpleasant over-air-conditioned journey through Utah and the Rockies.

I found a motel, got a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, stripped, and had a shower that lasted about an hour and a half. I watched TV like it was a new invention. A presidential campaign had been taking place all the time I’d been away and it was getting close to its climax. The governor of Arkansas was being tipped to edge out President Bush. It was boring, so instead I watched Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy and flipped between endless daytime soaps.

Читать дальше