You’re beautiful, she said.

I asked her her name but she wouldn’t tell me. She put her finger over my lips, she didn’t want to say anything now. Words were dangerous, they were reminders and could ruin everything.

I held her and touched her. Her breasts were small and her body was thin and supple and that hardness I’d seen in her yesterday was a reaction to us and was not reflected in her kisses and her touch and her warmth. She was so pale, and where Bridget was passionate and businesslike and pretty, she was all need. That was everything about her, and it was almost overwhelming. She was hungry for a body. No, not just a body, I could see that: it was me. It was me, and it almost hurt to be with her.

And this was me punishing Bridget for being with Darkey. Punishing Darkey for loving Bridget.

She could see that I was afraid that she was broken, fragile, but she showed me. She was tender and composed and urgent. She was all need. I kissed her bruises and her eyes and her mouth, and she kissed me and we spent the night giving and being given unto, and sleeping into the new day.

Vignettes: shopping in C-Town; crazy men yelling in the two-dollar cinema; drinks in the Four Provinces; evening collections with Scotchy; Fergal dinging a gypsy cab and having a go at the cabbie; a black girl’s body in Marcus Garvey Park; two lads going at it with a knife on 191st Street; Bridget leaning over and kissing me for the first time as we changed the kegs; an empty lot bursting with trees and life on MLK Boulevard, and opposite, a hurt guy on a bike splayed in front of the Manhattanville post office; rows of fresh fruit in West Side Market; flattened rats; pepper trees; whole plazas of urine; me and the boys extorting some guy in Fordham into giving us a ton a week for doing precisely nothing; the bakery on Lenox; soul food at M &G; delivering a sofa set for Darkey to some cousin in Yonkers, up two flights and past a goddamn corner; the Nation of Islam screaming at me at the A train stop on 125th; the doe-eyed girl with her boyfriend in the hall; Sunday service all along the hot street in the morning, Christ’s children in a merry wee conspiracy of happiness; choirs; the tiny, forgotten synagogue on 126th; the Ethiopian lady wandering half-naked in the lobby; Ratko’s Santa laugh as another bottle opens; rice and beans on 112th; KFC; McDonald’s; rice and beans at Floridita; M &G again; the Four P.; Bridget; Bridget again…

The whole summer’s events compressed into a single point. Eight weeks in one second. The colors, smells, humidity, tastes, all of it condensed into a moment, folded and pushed together like an old-fashioned brass collapsing telescope.

An instant. Held. So much brighter than Belfast. Faster and richer, too, and not in the sense of money.

Life flashed, and I was momentarily stunned. I got down.

Hit the deck.

Hit the deck.

Yelled.

Holy fuck.

Noise.

Breathed.

Breathing…

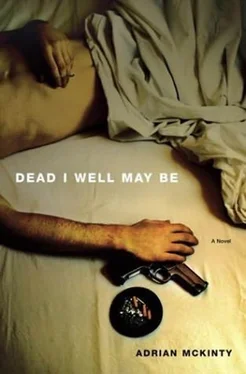

I was breathing hard, sweating, and then, to my horror, I realized that I’d been shot in the left hand, a ricochet. A chunk of flesh had been ripped away behind the knuckles, leaving an angry gash that was just figuring out that with this level of injury it really should be starting to bleed.

They must’ve got me when I’d stuck my hands up over my face and it had taken me and the hand some time to realize what was happening. What was happening, of course, was a cock-up of tremendous proportions, a cock-up perhaps just as big and scary as the multifarious and diverse fifteen-year-old-boy cock-ups I’d gotten myself into in North Belfast and Rathcoole. It didn’t, however, necessarily have to be a fatal cock-up, because we were all very close to the door and Dermot had blown the gaff by not having a man cover behind us to cut off an exit.

It was five days after the Shovel incident, and I was in a shoot-out at the long-postponed meeting at Dermot’s place. When I came on board, Scotchy had promised that there would be the occasional shoot-out. The way he said it was the way kids would tell you about a game of Cowboys and Indians. Scotchy said he’d been in Bandit Country and I’d been in North Belfast, so neither of us should be strangers to gunplay, but in America there was a glamour that attached to things. He and Fergal could talk up a storm about some shindig they’d gotten into in Inwood Park a year or two back: bullets whizzing, Fergal taking one in the foot, two black guys running for the hills by the end of it. The details were vague and unconvincing and informed, seemingly, by years of TV and the movies.

But this, unfortunately, was the real deal. Eight months working for Darkey, and the worst I’d seen was Scotchy and Andy giving some boy a powerful, coma-inducing hiding. No, be honest. The worse I’d seen was actually me and Shovel. I mean, I’d hit a couple of recalcitrant types myself, but mostly our actions could be implied with menaces. But now in the space of a few days I’d delivered Old World violence into a New World setting, and now I was in a real honest-to-Jesus firefight, one that conceivably I might get killed in. It was some kind of apotheosis, some kind of tear in the fabric of things, and if I was of a suspicious nature I might have been suspicious.

I was behind the bar with Sunshine, and on the other side in a more exposed position were Fergal and Scotchy. Andy, of course, was out in the car, and if he’d any sense at all in that thick head of his, that’s where he’d stay. Andy was only out of hospital that morning, and Scotchy, instead of letting him rest, had brought him down with us to a potentially hazardous assignment.

I really should have known to stay in bed, because today already had been atypical. The trains had all come promptly, the weather had taken a cooler turn, and although not a big believer in omens, I’d won twenty bucks on a scratch card in the fake bodega on 123rd. Unpleasantness was sure to follow.

Our original plan was to have Andy’s coming-off-the-sick party all day today but Sunshine had put flies in that ointment with his patience suddenly collapsing in the face of Dermot’s singular insistence that he was fucking “quits with you, Sunshine, and if you and Darkey know what’s good for you, you’ll be keeping out of my fucking way.”

Now Dermot’s men were shooting at us with automatic weapons, big ones, too, and they were carving up the bar above us and making a hell of a lot of noise, enough noise to grab the attention of the neighborhood and lure it away from the Yankees game. Sunshine was shaking like a Jell-O-molded pudding that has somehow attained sentience and is being shot at with machine guns. He was staring at me in abject terror. I was breathing.

What the fuck are you doing? Sunshine asked.

I was in no mood to give him an answer. Sunshine’s fabled brilliance with intelligence had let us all down here. There were at least two shooters and Dermot himself and maybe a bloody barman, and Sunshine had failed to warn us about any of this.

I’m centering my chi , I said.

What?

Centering my chi .

You’re centering your fucking chi? Sunshine asked, frightened.

Aye.

How long will that take?

Not too long. My life was flashing before my eyes earlier, I said, a little less angry with him now and hoping to calm his nerves.

It was?

Yeah.

And now you’re centering your chi ?

Aye.

The big Kalashnikovs, or whatever they were, were shooting at us from semidarkness in the lounge bar a good fifty feet away from our position. What Dermot’s plan had been was none too clear, because it didn’t seem to be the ideal place at all for an ambush. More than likely Dermot had told his boys to let us come completely into the pub and then open up on us from oblique angles; but the boys must have been inexperienced or jumpy or cracked up because they’d started as soon as we’d walked in. Sunshine and I had dived for the bar. Fergal and Scotchy had ended up near the tables. About a minute and a half had gone by, and I’d spent all of it flashing my recent life before my eyes and lying on the floor with Sunshine trying to figure what was going to happen next. It seemed to boil down to three possibilities: they’d get us, we’d get them, or maybe we’d all get nicked.

Читать дальше