Stan had backed to one corner of the stage and stood watching the audience quietly as they strained their necks upward, hanging on every word of the seeress. In the floor, which was a few inches above their eye level, was a square hole. Zeena stroked her forehead, covering her eyes with her hand. At the opening appeared a pad of paper, a grimy thumb holding it, on which was scrawled in crayon, “What to do with wagon? J. E. Giles.”

Zeena looked up, folding her arms with decision. “I get an impression- It’s a little cloudy still but it’s getting clearer. I get the initials J… E… G. I believe it’s a gentleman. Is that right? Will the person who has those initials raise his hand, please?”

An old farmer lifted a finger as gnarled as a grapevine. “Here, ma’am.”

“Ah, there you are. Thank you, Mr. Giles . The name is Giles, isn’t it?”

The crowd sucked in its breath. “I thought so. Now then, Mr. Giles, you have a problem, isn’t that right?” The old man’s head wagged solemnly. Stan noted the deep creases in his red neck. Old sodbuster. Sunday clothes. White shirt, black tie. What he wears at funerals. Tie already tied-he hooks it onto his collar button. Blue serge suit-Sears, Roebuck or a clothing store in town.

“Let me see,” Zeena went on, her hand straying to her forehead again. “I see- Wait. I see green trees and rolling land. It’s plowed land. Fenced in.”

The old man’s jaw hung open, his eyes frowning with concentration, trying not to miss a single word.

“Yes, green trees. Probably willow trees near a crick. And I see something under those trees. A- It’s a wagon.”

Watching, Stan saw him nod, rapt.

“An old, blue-bodied wagon under those trees.”

“By God, ma’am, it’s right there this minute.”

“I thought so. Now you have a problem on your mind. You are thinking of some decision you have to make connected with that wagon, isn’t that so? You are thinking about what to do with the wagon. Now, Mr. Giles, I would like to give you a piece of advice: don’t sell that old blue-bodied wagon.”

The old man shook his head sternly. “No, ma’am, I won’t. Don’t belong to me!”

There was a snicker in the crowd. One young fellow laughed out loud. Zeena drowned him out with a full-throated laugh of her own. She rallied, “Just what I wanted to find out, my friend. Folks, here we have an honest man and that’s the only sort I want to do any business with. Sure, he wouldn’t think of selling what wasn’t his, and I’m mighty glad to hear it. But let me ask you just one question, Mr. Giles. Is there anything the matter with that wagon?”

“Spring’s broke under the seat,” he muttered, frowning.

“Well, I get an impression that you are wondering whether to get that spring fixed before you return the wagon or whether to return it with the spring broken and say nothing about it. Is that it?”

“That’s it, ma’am!” The old farmer looked around him triumphantly. He was vindicated.

“Well, I’d say you had just better let your conscience be your guide in that matter. I would be inclined to talk it over with the man you borrowed it from and find out if the spring was weak when he loaned it to you. You ought to be able to work it out all right.”

Stan quietly left the stage and crept down the steps behind the draperies. He squeezed under the steps and came out beneath the stage. Dead grass and the light coming through chinks in the box walls, with the floor over his head. It was hot, and the reek of whisky made the air sweetly sick.

Pete sat at a card table under the stage trap. Before him were envelopes Stan had passed him on his way up to the seeress; he was snipping the ends off with scissors, his hands shaking. When he saw Stan he grinned shamefacedly.

Above them Zeena had wound up the “readings” and gone into her pitch: “Now then, folks, if you really want to know how the stars affect your life, you don’t have to pay a dollar, nor even a half; I have here a set of astrological readings, all worked out for each and every one of you. Let me know your date of birth and you get a forecast of future events complete with character reading, vocational guidance, lucky numbers, lucky days of the week, and the phases of the moon most conducive to your prosperity and success. I’ve only a limited amount of time, folks, so let’s not delay. They’re only a quarter, first come, first served and while they last, because I’m getting low.”

Stan slipped out of the sweatbox, quietly parted the curtains, stepped into the comparatively cooler air of the main tent, and sauntered over toward the soft drink stand.

Magic is all right, but if only I knew human nature like Zeena. She has the kind of magic that ought to take anybody right to the top. It’s a convincer-that act of hers. Yet nobody can do it, cold. It takes years to get that kind of smooth talk, and she’s never stumped. I’ll have to try and pump her and get wised up. She’s a smart dame, all right. Too bad she’s tied to a rumdum like Pete who can’t even get his rhubarb up any more; so everybody says. She isn’t a bad-looking dame, even if she is a little old.

Wait a minute, wait a minute. Maybe here’s where we start to climb…

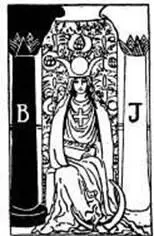

The High Priestess

Queen of borrowed light who guards a shrine between the pillars Night and Day.

BEYOND the flowing windshield the taillight of the truck ahead wavered ruby-red in the darkness. The windshield wiper’s tock-tock-tock was hypnotic. Sitting between the two women, Stan remembered the attic at home on a rainy day-private, shut off from prying eyes, close, steamy, intimate.

Molly sat next to the door on his right, leaning her head against the glass. Her raincoat rustled when she crossed her legs. In the driver’s seat Zeena bent forward, peering between the swipes of the wiper, following blindly the truck that held the snake box and the gear for the geek show, Bruno’s weights, and Martin’s baggage with the tattoo outfit. The geek, with his bottle, had crawled into a little cavern made by the piled gear and folded canvas.

In her own headlights, when the procession stopped at a crossing, Zeena could see Bruno’s chunky form in a slicker swing from the cab and plod around to the back to look at the gear and make sure the weights were fast. Then he came over and stepped on the running board. Zeena cranked down the window on her side. “Hi, Dutchy-wet enough for you?”

“Joost about,” he said softly. “How is things back here? How is Pete?”

“Right in back of us here having a snooze on the drapes. You reckon we’ll try putting up in this weather?”

Bruno shook his head. His attention crept past Zeena and Stan, and for a moment his eyes lingered sadly on Molly, who had not turned her head.

“I joost want to make sure everything is okay.” He turned back into the rain, crossing the streaming beam of the headlights and vanishing in the dark. The truck ahead began to move; Zeena shifted gears.

“He’s a fine boy,” she said at last. “Molly, you ought to give Bruno a chance.”

Molly said, “No, thanks. I’m doing okay. No, thanks.”

“Go on-you’re a big girl now. Time you was having some fun in this world. Bruno could treat you right, by the looks of him. When I was a kid I had a beau that was a lumberjack-he was built along the lines of Bruno. And oh, boy!”

As if suddenly aware that her thigh was pressed close to Stan’s, Molly squeezed farther into the corner. “No, thanks. I’m having fun now.”

Читать дальше