The truck bounced off the side road in a cloud of dust, white under the full moon, and turned into a state highway. Zeena drove carefully to spare the truck and Joe sat next to her, one arm on her shoulders to steady himself when they stopped suddenly or slowed down. Stan was next to the door of the cab, his palmistry banners in a roll between his knees.

Town lights glittered ahead as they topped a gradual rise. They coasted down it.

“Almost there, Stan.”

“You’ll make it, kid,” Joe said. “McGraw’s a hard cookie, but he ain’t a nickel-nurser once you got him sold.”

Stan was quiet, watching the bare streets they were rolling through. The bus station was a drugstore which kept open all night. Zeena stopped down the block and Stan opened the door and slid out, lifting out the banners.

“So long, Zeena-Joe. This-this was the first break I’ve had in a hell of a while. I don’t know how-”

“Forget it, Stan. Joe and me was glad to do what we could. A carny’s a carny and when one of us is jammed up we got to stick together.”

“I’ll try riding the baggage rack on this bus, I guess.”

Zeena let out a snort. “I knew I’d forgot something. Here, Stan.” From the pocket of her overalls she took a folded bill and, leaning over Joe, pressed it into the mentalist’s hand. “You can send it back at the end of the season. No hurry.”

“Thanks a million.” The Great Stanton turned, with the rolled canvas under his arm, and walked away toward the drugstore. Halfway down the block he paused, straightened, threw back his shoulders and then went on, holding himself like an emperor.

Zeena started the truck and turned it around. They drove out of town in a different direction and then took a side road which cut into the highway further south, turning off it to mount a bluff overlooking the main drag. “Let’s wait here, snooks, and try to get a peek into the bus when it goes by. I feel kind of funny, not being able to see him to the station and wait until it came along. Don’t seem hospitable.”

“Only smart thing to do, Zee. A fellow as hot as him.”

She got out of the cab and her husband hopped after her; they crossed a field and sat on the bank. Above them the sky had clouded over, the moon was hidden by a thick ceiling.

“You reckon he’ll make it, Joe?”

Plasky shifted his body on his hands and leaned forward. Far down the pale concrete strip the lights of a bus rose over the grade. It picked up speed, tires singing on the roadbed, as it bore down toward them. Through its windows they could make out the passengers-a boy and a girl, in a tight clinch on the back seat. One old man already asleep. It roared below the bank.

Stanton Carlisle was sharing a seat with a stout woman in a gay flowered-print dress and a white sailor straw hat. He was holding her right hand, palm up, and was pointing to the lines.

Joe Plasky sighed as the bus tore past them into darkness with a fading gleam of ruby taillights. “I don’t know what’ll happen to him,” he said softly, “but that guy was never born to hang.”

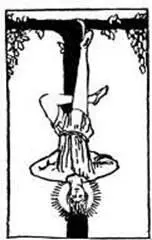

The Hanged Man

hangs head downward from the living wood .

IT WAS a cheap straw hat, but it added class. He was the type of guy who could wear a hat. The tie chain came from the five-and-ten, but with the suit and the white shirt it looked like the real thing. The amber mirror behind the bar always makes you look tanned and healthy. But he was tanned. The mustache was blackened to match the hair-dyeing job Zeena had done.

“Make mine a beer, pal.”

He took it to a table, put his hat on an empty chair and unfolded a newspaper, pretending to read it. Forty-five minutes before the local bus left. They don’t know who they’re looking for up there-no prints, no photo. Stay out of that state and they’ll look for you till Kingdom Come.

The beer was bitter and he began to feel a little edge from it. This was all right. Keep it at beer for a while. Get a stake, working the mitt camp. Get a good wad in the grouchbag and then try working Mexico. They say the language is a cinch to learn. And the damn country’s wide open for ragheads. They advertise in all the papers down there. Give that mess with the cop time to cool and I can come back in a few years and start working California. Take a Spanish name maybe. There’s a million chances.

A guy who’s good at the cold reading will never starve.

He opened the newspaper, scanning the pictures, thinking his way along through the days ahead. I’ll have to hustle the readings and put my back into it. In a carny mitt camp you got to spot them quick, size ’em up and unload it in a hurry. Well, I can do it. I should have stayed right with the carny.

Two pages of the paper stuck and he went back and pried them apart, not caring what was on them, just so as not to skip any. In Mexico…

The picture was alone on the page, up near the top. He looked at it, concentrating on the woman’s face, his glance merging the screen of black dots that composed it, filling in from memory its texture, contour, color. The scent of the sleek gold hair came back to him, the sly twist of her little tongue. The man looked twenty years older; he looked like a death’s head-scrawny neck, flabby cheeks…

They were together. They were together. Read it. Read what they’re doing.

PSYCHOLOGIST WEDS MAGNATE

In a simple ceremony. The bride wore a tailored…Best man was Melvin Anderson, long-time friend and advisor…Honeymoon cruise along the coast of Norway…

Somebody was shaking him, talking at him. Only it wasn’t any grass tuft-it was a beer glass. “Jees, take it easy, bud. How’d ya bust it? Ya musta set it down too hard. We ain’t responsible, you go slinging glasses around and get cut. Why don’t ya go over to the drugstore. We ain’t responsible…”

Darkness of street darkness with the night’s eyes up above the roof cornices oh Jesus he was bleeding suitable for a full evening’s performance gimme a rye and plain water, yeah, a rye make it a double.

It’s nothing, I caught it on a nail, doc. No charge? Fine, doc. Gimme a rye-yeah, and plain water better make it a double rye and plain water seeping into the tire tracks where the grownups were everywhere.

I ain’t pushing, bud, let’s have no hard feelings, I’m your friend, my friend I get the impression that when you were a lad there was some line of work or profession you wanted to follow and furthermore you carry in your pocket a foreign coin or lucky piece you can see Sheriff that the young lady cannot wear ordinary clothes because thousands of volts of electricity cover her body like a sheath and the sequins rough against his fingers as he unhooked the smoothness of her breasts trembling pressing victory into we’ll make a team right to the top and they give you a handout like a tramp at a back door but the doors have been closed, gentlemen, let them look for threads till Kingdom Come and the old idiot gaping there in the red light of the votive candle oh Jesus you frozen-faced bitch give me that dough yeah make it a rye, water on the side…

You could hardly see the platform for the smoke and the waiter wore a butcher’s apron his sleeves were rolled up and his arms had muscles like Bruno’s only they were covered with black hair you had to pay him every time and the drinks were small get out of this crummy joint and find another one but the dame was singing while the guy in a purple silk shirt rattled on the runt piano the old bag had on a black evening dress and a tiara of rhinestones

Put your arms around me, honey, hold me tight!

Читать дальше