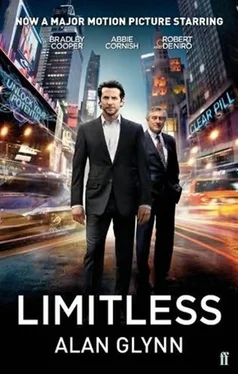

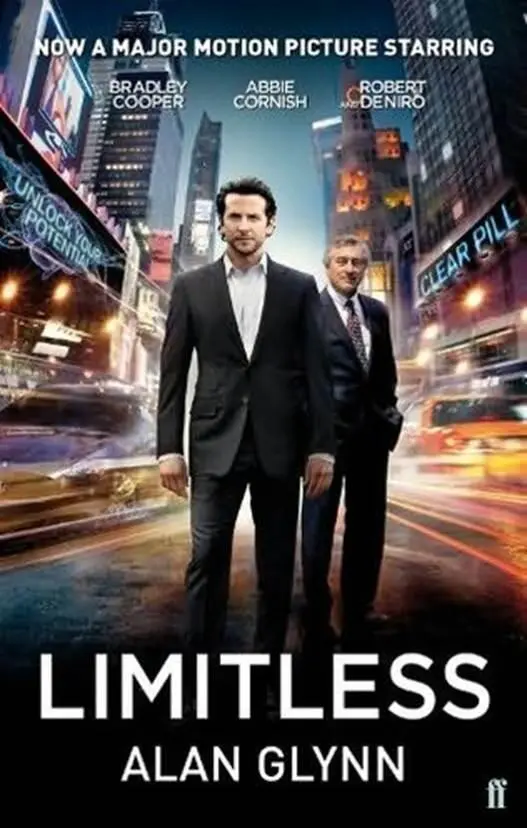

Alan Glynn

The Dark Fields aka Limitless

First published as The Dark Fields in 2001 by Little Brown & Company

First published as Limitless in 2011

I wish to thank the following people for their help and support, both moral and editorial: Eithne Kelly, Declan Hughes, Douglas Kennedy, Antony Harwood, Andrew Gordon, Liam Glenn, Eimear Kelly, Kate O’Carroll and Tif Eccles.

He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

IT’S GETTING LATE.

I don’t have too sharp a sense of time any more, but I know it must be after eleven, and maybe even getting on for midnight. I’m reluctant to look at my watch, though – because that will only remind me of how little time I have left.

In any case, it’s getting late.

And it’s quiet . Apart from the ice-machine humming outside my door and the occasional car passing by on the highway, I can’t actually hear a thing – no traffic, or sirens, or music, or local people talking, or animals making weird nightcalls to each other, if that’s what animals do. Nothing. No sounds at all. It’s eerie, and I don’t really like it. So maybe I shouldn’t have come all the way up here. Maybe I should have just stayed in the city, and let the time-lapse flicker of the lights short-circuit my now preternatural attention span, let the relentless bustle and noise wear me down and burn up all this energy I’ve got pumping through my system. But if I hadn’t come up here to Vermont, to this motel – to the Northview Motor Lodge – where would I have stayed? I couldn’t very well have inflicted my little mushroom-cloud of woes on any of my friends, so I guess I had no option but to do what I did – get in a car and leave the city, drive hundreds of miles up here to this quiet, empty part of the country…

And to this quiet, empty motel room, with its three different but equally busy décor patterns – carpet, wallpaper, blankets – vying, screaming , for my attention – to say nothing of the shopping-mall artwork everywhere, the snowy mountain scene over the bed, the Sunflowers reproduction by the door.

I am sitting in a wicker armchair in a Vermont motel room, everything unfamiliar to me. I’ve got a laptop computer balanced on my knees and a bottle of Jack Daniel’s on the floor beside me. I’m facing the TV set, which is bolted to the wall in the corner, and is switched on, tuned to CNN, but with the sound turned right down. There is a panel of commentators on the screen – national security advisers, Washington correspondents, foreign policy experts – and although I can’t hear them, I know what they’re talking about… they’re talking about the situation, the crisis, they’re talking about Mexico.

Finally – giving in – I look at my watch.

I can’t believe that it’s been nearly twelve hours already. In a while, of course, it will be fifteen hours, and then twenty hours, and then a whole day. What happened in Manhattan this morning is receding, slipping back along all those countless, small-town Main Streets, and along all those miles of highway, hurtling backwards through time, and at what feels like an unnaturally rapid pace. But it is also beginning to break up under the immense pressure, beginning to crack and fragment into separate shards of memory – while simultaneously remaining, of course, in some kind of a suspended, inescapable present tense, set hard, un breakable… more real and alive than anything I can see around me here in this motel room.

I look at my watch again.

The thought of what happened sets my heart pounding, and audibly, as if it’s panicking in there and will shortly be forcing its way, thrashing and flailing, out of my chest. But at least my head hasn’t started pounding. That will come, I know, sooner or later – the intense pin-prick behind the eyeballs spreading out into an excruciating, skull-wide agony. But at least it hasn’t started yet.

Clearly, though, time is running out.

*

So how do I begin this?

I suppose I brought the laptop with me intending to get everything down on a disk, intending to write a straightforward account of what happened, and yet here I am hesitating, circling over the material, dithering around as if I had a couple of months at my disposal and some sort of a reputation to protect. The thing is, I don’t have a couple of months – I probably only have a couple of hours – and I don’t have any reputation to protect, but I still feel as if I should be going for a bold opening here, something grand and declamatory, the kind of thing a bearded omniscient narrator from the nineteenth century might put in to kick-start his latest 900-pager.

The broad stroke.

Which, I feel, would go with the general territory.

But the plain truth is, there was nothing broad-stroke-ish about it, nothing grand and declamatory in how all of this got started, nothing particularly auspicious in my running into Vernon Gant on the street one afternoon a few months ago.

And that, I suppose, really is where I should start.

VERNON GANT.

Of all the various relationships and shifting configurations that can exist within a modern family, of all the potential relatives that can be foisted upon you – people you’ll be tied to for ever, in documents, in photographs, in obscure corners of memory – surely for sheer tenuousness, absurdity even, one figure must stand towering above all others, one figure, alone and multi-hyphenated: the ex-brother-in-law.

Hardly fabled in story and song, it’s not a relationship that requires renewal. What’s more, if you and your former spouse don’t have any children then there’s really no reason for you ever, ever to see this person again in your entire life. Unless, of course, you just happen to bump into him in the street and are unable, or not quick enough, to avoid making eye contact.

It was a Tuesday afternoon in February, about four o’clock, sunny and not too cold. I was walking along Twelfth Street at a steady clip, smoking a cigarette, heading towards Fifth Avenue. I was in a bad mood and entertaining dark thoughts about a wide range of subjects, my book for Kerr & Dexter – Turning On: From Haight-Ashbury to Silicon Valley – chief among them, though there was nothing unusual about that, since the subject thrummed relentlessly beneath everything I did, every meal I ate, every shower I took, every ballgame I watched on TV, every late-night trip to the corner store for milk, or toilet-paper, or chocolate, or cigarettes. My fear on that particular afternoon, as I remember, was that the book just wouldn’t hang together. You’ve got to strike a delicate balance in this kind of thing between telling the story and… telling the story – if you know what I mean – and I was worried that maybe there was no story, that the basic premise of the book was a crock of shit. In addition to this, I was thinking about my apartment on Avenue A and Tenth Street and how I needed to move to a bigger place, but how that idea also filled me with dread – taking my books down off their shelves, sorting through my desk, then packing everything into identical boxes, forget it. I was thinking about my ex-girlfriend, too – Maria, and her ten-year-old daughter, Romy – and how I’d clearly been the wrong guy to be around that situation. I never used to say enough to the mom and couldn’t rein in my language when I was talking to the kid. Other dark thoughts I was having: I smoked too much and had a sore chest. I had a host of companion symptoms as well, niggly physical things that showed up occasionally, weird aches, possible lumps, rashes, symptoms of a condition maybe, or a network of conditions. What if they all held hands one day, and lit up, and I keeled over dead?

Читать дальше