“Oh yeah, I’m fine. I did that on purpose,” I tell her in earnest, as the skid truly had been intentional. I catch her glance, a good-natured shot that tells me she believes me but thinks I’m silly for not finding an easier way down. I look around and, seeing an obviously less risky access route that would have avoided the slide, I feel slightly foolish.

Five minutes later, we come to the first section of difficult downclimbing, a steep descent where it’s best to turn in and face the rock, reversing moves that one would usually use for climbing up. I go down first, then swing my backpack around to retrieve my video camera and tape Megan and Kristi. Kristi pulls a fifteen-foot-long piece of red webbing out of her matching red climber’s backpack and threads it through a metal ring that previous canyoneering parties have suspended on another loop of webbing tied around a rock. The rock is securely wedged in a depression behind the lip of the drop-off, and the webbing system easily holds a person’s weight. Grasping the webbing, Megan backs herself down over the drop-off. She has to maneuver around an overhanging chockstone-a boulder suspended between the walls of the canyon-that blocks an otherwise easy scramble down into the deepening slot. Once Megan is down, Kristi follows skittishly, as she doesn’t completely trust the webbing system. After she’s down, I climb back up to retrieve Kristi’s webbing.

We walk thirty feet and come to another drop-off. The walls are much closer now, only two to three feet apart. Megan throws her backpack over the drop before shimmying down between the walls, while Kristi takes a few pictures. I watch Megan descend and help her by pointing out the best handholds and footholds. When Megan is at the bottom of the drop, she discovers that her pack is soaking wet. It turns out her hydration-system hose lost its nozzle when she tossed the pack over the ledge, and was leaking water into the sand. She quickly finds the blue plastic nozzle and stops the water’s hemorrhage, saving her from having to return to the trailhead. While it’s not a big deal that her pack is wet, she has lost precious water. I descend last, my pack on my back and my delicate cameras causing me to get stuck briefly between the walls at several constrictions. Squirming my way over small chockstones, I stem my body across the gap between the walls to follow the plunging canyon floor. There is a log wedged in the slot at one point, and I use it like a ladder on a smooth section of the skinny-people-only descent.

While the day up above the rim rock is getting warmer, the air down in the canyon becomes cooler as we enter a four-hundred-yard-long section of the canyon where the walls are over two hundred feet high but only fifteen feet apart. Sunlight never reaches the bottom of this slot. We pick up some raven’s feathers, stick them in our hats, and pause for photographs.

A half mile later, several side canyons drop into the Main Fork where we are walking, as the walls open up to reveal the sky and a more distant perspective of the cliffs downcanyon. In the sun once again, we stop to share two of my melting chocolate bars. Kristi offers some to Megan, who declines, and Kristi says, “I really can’t eat all this chocolate by myself…Never mind, yes I can,” and we laugh together.

We come to an uncertain consensus that this last significant tributary off to the left of the Main Fork is the West Fork, which means it’s the turnoff for Kristi and Megan to finish their circuit back to the main dirt road about four miles away. We get hung up on saying our goodbyes when Kristi suggests, “Come on, Aron, hike out with us-we’ll go get your truck, hang out, and have a beer.”

I’m dedicated to finishing my planned tour, so I counter, “How about this?-you guys have your harnesses, I have a rope-you should come with me down through the lower slot and do the Big Drop rappel. We can hike out…see the Great Gallery…I’ll give you a lift back to your truck.”

“How far is it?” asks Megan.

“Another eight miles or so, I think.”

“What? You won’t get out before dark! Come on, come with us.”

“I really have my heart set on doing the rappel and seeing the petroglyphs. But I’ll come around to the Granary Spring Trailhead to meet you when I’m done.”

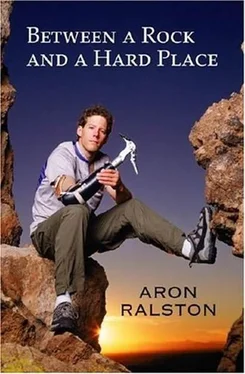

This they agree to. We sit and look at the maps one more time, confirming our location on the Blue John map from the canyoneering guidebook we’d each used to find this remote slot. In my newest copy of Michael Kelsey’s Canyon Hiking Guide to the Colorado Plateau, there are over a hundred canyons described, each with its own hand-sketched map. Drawn by Kelsey from his personal experience in each canyon, the technical maps and route descriptions are works of art. With cross sections of tricky slots, identifications of hard-to-find petroglyphs and artifact sites, and details of required rappelling equipment, anchor points, and deep-water holes, the book offers enough information for you to sleuth your way through a decision or figure out where you are, but not a single item extra. After we put away the maps, we stand up, and Kristi says, “That picture in the book makes those paintings look like ghosts; they’re kind of spooky. What kind of energy do you think you’ll find at the Gallery?”

“Hmm.” I pause to consider her question. “I dunno. I’ve felt pretty connected looking at petroglyphs before; it’s a good feeling. I’m excited to see them.”

Megan double-checks: “You’re sure you won’t come with us?” But I’m as set on my choice as they are on theirs.

A few minutes before they go, we solidify our plan to meet up around dusk at their campsite back by Granary Spring. There’s going to be a Scooby party tonight of some friends of friends of mine from Aspen, about fifty miles away, just north of Goblin Valley State Park, and we agree to caravan there together. Most groups use paper plates as improvised road signs to an out-of-the-way rendezvous site; my friends have a large stuffed Scooby-Doo to designate the turnoff. After what I’ll have completed-an all-day adventure tour, fifteen miles of mountain biking and fifteen miles of canyoneering-I’ll have earned a little relaxation and hopefully a cold beer. It will be good to see these two lovely ladies of the desert again so soon, too. We seal the deal by adding a short hike of Little Wild Horse Canyon, a nontechnical slot in Goblin Valley, to the plan for tomorrow morning. New friends, we part ways at two P.M. with smiles and waves.

Alone once again, I walk downcanyon, continuing on my itinerary. Along the way, I think through the remainder of my vacation time. Now that I have a solid plan for Sunday to hike Little Wild Horse, I speculate that I’ll get back to Moab around seven o’clock that evening. I’ll have just enough time to get my gear and food and water prepared for my bike ride on the White Rim in Canyonlands National Park and catch a nap before starting around midnight. By doing the first thirty miles of the White Rim by headlamp and starlight, I should be able to finish the 108-mile ride late Monday afternoon, in time for a house party my roommates and I have planned for Monday night.

Without warning, my feet stumble in a pile of loose pebbles deposited from the last flash flood, and I swing my arms out to catch my balance. Instantly, my full attention returns to Blue John Canyon.

My raven feather is still tucked in the band at the back of my blue ball cap, and I can see its shadow in the sand. It looks goofy-I stop in the open canyon and take a picture of my shadow with the feather. Without breaking stride, I unclip my pack’s waist belt and chest strap, flip my pack around to my chest, and root around inside the mesh outer pouch until I can push play on my portable CD player. Audience cheers give way to a slow lilting guitar intro and then soft lyrics:

Читать дальше