Each toss takes two minutes to set up, and my first dozen tries fall short, bouncing off the wall or the face of the chockstone, or slipping out of the crack before the carabiners can wedge tightly. I refine my procedure of stacking the trailing rope so it unfurls with as little drag as possible, and my accuracy improves. Of the next dozen tries, five of them land my carabiners in the crack, but each time they pull free. I add a fourth carabiner to my improvised grappling device. With a brilliantly lucky throw on my next try, the carabiner bundle hits the wide mouth of the crack and drops into the pinch point, and with a tug at just the right moment, the block wedges tight. I test the constriction’s strength and watch the carabiners bite into the rock. I’m worried that the sandstone pinch point will break and let the ’biners loose, but the metal links jam hard against one another, and the rock holds the stress without a problem. As a wave of happiness washes over my tired mind, I tie another figure-eight knot on a loop of the anchored rope that drapes back over the chockstone near my waist, and I clip myself to the system. With two adjustments of the knot to cinch my harness a little higher and keep my weight from tugging on my arm, I finally lean back and take some weight off my legs. Ahhhhh. I relax for the first time, and my body celebrates a victory over the strain of standing still for over twelve hours.

I take my water bottle from its perch and have a small sip right at three A.M. My respite is complete but disappointingly short-just fifteen minutes until the harness restricts the blood flow to my legs and I have to stand again. There is the risk that if I sit too long, I will cause damage to my legs or cause a blood clot to form. Long before that danger manifests, the harness makes my hamstrings ache where the leg loops hold my weight. I alternate standing and sitting, establishing a pattern that I repeat in twenty-minute intervals.

In these coldest hours before dawn, from three until six, I take up my knife again and hack at the chockstone. I can chip at the rock either standing or sitting. I continue to make minimal but visible progress in the divot. After sips of water at four-thirty and six A.M., I take stock of the rock I’ve managed to eliminate during the past fifteen hours of tiring work. I estimate that at the rate I’ve averaged, I would have to chip at the rock for 150 hours to free my hand. Discouraged, I know I will need to do something else to improve my situation.

Just after eight o’clock, I hear a rushing noise filtering down from the canyon above me, a wind swoosh that pulses three times. I look up as a large black raven flies over my head. He’s heading upcanyon, and with each flap of his wings, echoes filter down to my ears. At the third flap, he screeches a loud “Ca-caw” and then disappears from my window of the overhead world. It’s still clammy cold in the depths of the canyon fissure, but I can see bright daylight on the north wall seventy feet above me. Broken strands of stratus clouds float by. I turn off my headlamp. I have made it through the night.

Around nine-thirty A.M. a dagger of sunlight appears behind me on the canyon floor. The light blade is teasingly close but still three feet behind my shoes. I haven’t yet fully rewarmed from the night’s chill, and I yearn for even a small touch of sun on my skin. After five minutes, the dagger has stabbed toward my heels enough that when I step down next to the hole where I dropped my keys, stretching my body until my arm pulls at my wrist, I can extend my left leg behind me so the sunshine caresses my ankle and lower calf. For ten minutes, I hold still, alternating between stretching out my left and then my right leg as the sunlight moves across the canyon floor. Like a yoga pose, this sun stretch welcomes a new day. The question crosses my mind of how many mornings will I be here to perform this matinal rite, but I push it back and relish the soothing warmth on my calves. Climbing up the north wall above my right leg, the light dagger bends and warps over the sandstone undulations until it ascends above my leg’s reach. Watching the beam scale the last three feet to where a suspended chockstone blocks it from my view, I realize it is the only direct sun I will get during the day.

With the sunlight’s presence, my emotional status lifts, and I feel rejuvenated for a time. Taking advantage of this positive infusion, I take up my knife and begin another two-hour cycle of pecking at the rock. I speculate on the odds of being found and the timing of when outside efforts will initiate a potential search. It looks bleak from every angle. Kristi and Megan barely know me. When I didn’t show up at their truck late yesterday afternoon, they probably thought I blew them off. They don’t know what my truck looks like, either, so even if they went over to the Horseshoe Canyon Trailhead, they wouldn’t know if my vehicle was there or not. Since I didn’t confirm with Brad and Leah that I would see them at the Scooby party, they wouldn’t be alerted to a problem. My roommates will miss me, but they don’t know where I am. If they should get so concerned to notify the Aspen police, the authorities won’t do anything until Tuesday night, at the earliest, once I’m overdue by over twenty-four hours.

It seems more probable to me that my manager at the Ute Mountaineer will call my parents to find out why I haven’t shown up for work. At that point, maybe they’ll get the police to poll my credit-card companies for my recent purchasing history and track me to Moab. This thought causes me to mentally slap myself, thinking about the purchases I made-I used my credit card only for gas in Glenwood Springs, where the highway from Aspen meets the interstate. I could have gone either east or west from there. I used my debit card to get groceries and top off my gas tank in Moab before I drove in to Horseshoe. Or did I? Maybe I used my credit card. Now I can’t remember. I hope it’s part of the missing-person’s procedure to check debit purchases, too.

If the police notify the National Park Service and the NPS initiates a general search on Wednesday, they’re unlikely to find my vehicle right away-the commanders will focus on the areas closer to Moab first. I saw a sign at the trailhead notifying visitors that rangers lead weekend tours down into Horseshoe Canyon to the major pictograph panels; the best shot for a ranger to find my truck will be when they come back to Horseshoe on Saturday, if they’re looking for it by then. A lucky strike, or more thorough second-stage canvasing, might mean they pinpoint my truck in the first day of searching, Thursday, and by the time they sweep the canyon and move all the way through Blue John, it’ll be Friday.

Friday, then, before someone pops his or her head over that chockstone ten feet in front and above me.

Friday.

But that’s at the earliest. Sunday’s more likely to be the day the searchers get to me, given the rangers’ schedule. Sunday, a week from today.

Without water, people die in a lot less than a week. I’ll be shocked if I survive until Tuesday morning. There’s no way I’ll make it to Friday. No way.

And I’ll be mummified by Sunday.

How to Become a Retired Engineer in Just Five Short Years

Deep Play: whereby what [one] stands to win from a gamble can never equal the enormity of what [one] will lose.

– JOE SIMPSON, Dark Shadows Falling

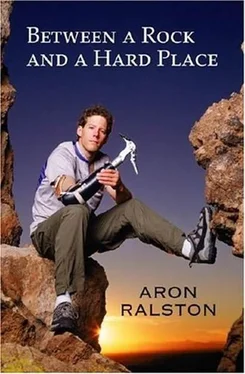

IN THE YEAR after my encounter with the stalking black bear in the Grand Tetons, I selected three climbing projects that would come to occupy my entire recreational focus: I would climb all of the Colorado fourteeners; I would climb all of them solo in winter (something that had never been done before); and I would ascend to the highest point in every state in the U.S. In late June 1997, I started my job at Intel, which seemed like a piece of cake compared to being hunted by a winter-thin bear.

Читать дальше