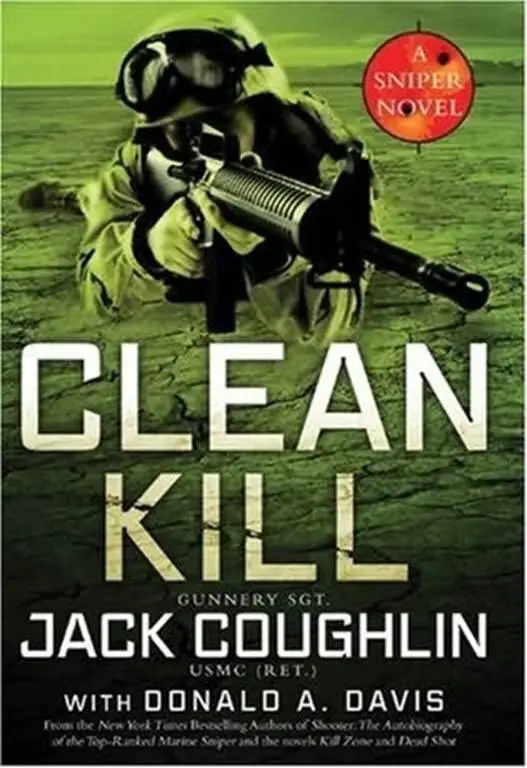

Jack Coughlin, Donald A. Davis

Clean Kill

The third book in the Sniper series, 2010

GUNNERY SGT. JACK COUGHLIN, USMC (RET.)

WITH DONALD A. DAVIS

PAKISTAN

F OR ONLY A MOMENT,less time than needed to take a breath, Gunnery Sergeant Kyle Swanson lifted his eyes from the dark path uncoiling before him and looked above the surrounding snow-covered peaks. A crescent moon rode in the cold night sky, with a shadowed edge so clean that the Marine sniper could make out the pimpled edges of individual craters with his naked eye. An early astronaut once described the lunar emptiness as magnificent desolation, and Swanson thought the same description was a good fit for the sheer and ragged mountains of western Pakistan. Up, down, or sideways, no matter where you looked, there was nothing in these badlands but more nothing. His eyes went back to the narrow trail, and he used his left hand to brush the stone face of the mountain, feeling for outcroppings of rock or tufts of weeds that could provide handholds, while he kept his boots at least six inches from edge of the trace. Beyond that was only a sheer drop of perhaps a thousand feet into a black chasm.

“I vote that next time, we just dump a bunch of cruise missiles on this place,” said Staff Sergeant Joe Tipp, who was climbing right behind him. “My legs are on fire. Cupla cruise missiles would have saved us from humping these damned mountains.”

The six Marines from Task Force Trident had been on the move for three consecutive nights, following a surly Afghan guide along impossible trails, up into the high elevations where the air was thin, then down into boulder-studded valleys, then up again. Before the dawns, they would take hide spots, set a guard rotation, and fall asleep exhausted, with every muscle sore and their weapons at hand. The only way through the Spin Ghars was to put one boot in front of another.

“A cruise missile wouldn’t deliver the proper message, Joe. We don’t want to just whip their asses; they have to know they’ve been beaten. This has to be up close and personal,” Swanson said over his shoulder as he forced his protesting legs to make one more step, then another. Two short grenade launchers rode atop his heavy pack, while an AK-47 assault rifle was hooked on the chest harness, and encased in a special bag over his shoulder was a Russian-made SV-98 sniper rifle. Balancing the seventy-pound load was as important as the footwork.

“You really get off on sending this kind of message, don’t you?”

Swanson snorted. “Bet your ass. Now shut up and climb.”

This was their fourth black raid on hidden training camps across the border in the past three months. The official version of the mission stated that it was just a snoop-and-poop job by scouts from the U.S. Marine Special Operations Command, MARSOC, and the men would stay clearly inside of Afghanistan and under no circumstances venture into Pakistan. American and other NATO troops made such sweeps every day, probing for the elusive Taliban and al Qaeda terrorists.

They had ridden out from a forward operating base in three closed Humvees, went through a couple of small villages of mud huts so they would be seen by curious eyes and reported up the terrorist grapevine as heading north. Once in the wilderness, darkness fell and things changed. The Humvees turned east at a dim intersection known as the Camel Crossroads and drove without lights for an hour over a rotten road, following deep ruts up the incline toward the mountain passes. They stopped. Eight Marines and the guide dismounted, and the vehicles returned to the crossroads and continued north to another forward operating base, again intentionally attracting the notice of enemy spies who concluded it was a routine resupply run, not worth worrying about.

By the end of the first night, the commandos were deep in the mountains, at an isolated and abandoned observation position that overlooked some of the most forbidding terrain on the planet. They rested all day, and things changed again that night. Two Marines were left behind to set up a communications station that would transmit periodic false mission reports back to headquarters. The rest stepped out, wearing old clothes purchased in Afghan bazaars, carrying a variety of weapons that were not made in America and without any identification. Then they fell off the map.

Soon, not even the radio team knew where they were. No colored pins on maps at any base showed their position or their target. No unmanned Predators circled overhead for surveillance, and if things went bad, no fighter-bombers would be zooming in for air support and there would be no rescue helicopter. There was absolutely no indication that any Americans were in the Paki backyard, which meant there could be no leaks to the various tribal warlords of questionable loyalties.

Kyle climbed on, in the company of fighting men that he knew and trusted, all of them fully aware that there would be no after action reports, no medals for bravery, no mentions in the media, no memoirs later in life when they were all grandfathers and retired. Whatever happened out here, stayed here.

The only unknown was the Afghan guide, who was only about as trustworthy as any of the locals. He had worked for the Agency for five years and was given a plastic-wrapped brick of $100 bills in payment to take them into the forbidden zone. He would not be a problem. Either he did as he was told or he would be killed and left in the mountains. Such was Kyle Swanson’s unforgiving world.

Climbing the rugged terrain with him now were five experienced commandos, none below the rank of sergeant or with less than seven years in the Corps. Joe Tipp was right behind him, occasionally bitching about life in general. Next was Staff Sergeant Darren Rawls, a tall African-American who was a natural athlete and hardly felt the muscle pains shared by the others on the mountain. Captain Rick Newman was in the middle of the line, technically in command of the operation but with the primary task of doing officer stuff, like talking to other officers when required, so Swanson could do his job. The fifth was red-haired Staff Sergeant Travis Stone, a grinning little killer rat. Trailing and covering the rear was the wiry and always-silent Sergeant Eliot Brenner.

Just before the mission’s fourth daybreak, as the serpentine trail descended toward a broad plateau, the guide suddenly stopped, then scurried back to Swanson. The patrol froze, instantly alert as the possibility of action replaced the drudge of climbing.

“What is it?” Kyle asked.

The Afghan pointed toward a long and rocky ridge and said in fractured English, “Al Qaeda, mister. Taliban. Just there.”

Swanson shed his pack and crawled forward on elbows and knees to a cluster of big rocks that allowed him to peer downward without exposing his head on the horizon. At the foot of the steep mountainside was a valley floor about five miles distant, where a crude camp of tents and small structures had been built.

Captain Newman crawled up and flopped beside Kyle and scanned the valley with his binos. “Bingo. We’re here.”

“Yep,” Swanson confirmed. “Let’s get settled.”

The Tridents spread out and found individual hides for the day, caught some sleep and spent their waking hours counting enemy noses and charting range cards to the various huts and landmarks. They did not speak, just watched the base camp in which the terrorists believed they were invulnerable. The six silent men were deep in the forbidding mountains, where their enemy had been protected by a truce between the local warlords and the Pakistani army, left alone for so long they felt free do as they wished.

Читать дальше