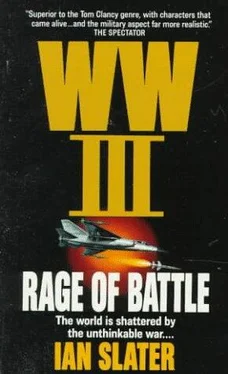

Ian Slater - Rage of Battle

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian Slater - Rage of Battle» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, ISBN: 1991, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Rage of Battle

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:0-345-46514-8

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Rage of Battle: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Rage of Battle»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Rage of Battle — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Rage of Battle», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Soviet and East German bombers could not penetrate the NATO air screen thrown up around avianosets Angliya— “carrier England”—where, though exhausted by sometimes more than seven sorties a day, pilots of the RAF, USAF, and German Luftwaffe forming NATO’s Second Allied Tactical Air Force continued to go up against the swarms of MiG-23-escorted “Backfire” and Badger-C bombers, the Soviet fighters carrying Kitchen and Kingfish air-to-surface missiles. Despite their pilots’ fatigue and a crash rate of 5.2 percent — which didn’t sound like much to the layman at home but which meant that after just ten sorties, you had only a fifty-fifty chance of coming back alive — the NATO air force commanders deep in the Börfink bunker before it was overrun had kept the Soviets at bay in the air. What the HQ of Second Tactical Air Force, now in the south at Ramstein, wanted — and what the U.K. Royal Air Force command in High Wycombe prayed for — was foul weather.

While this would complicate the already insufficient supply lines across the English Channel, including the floating oil pipeline, NATO preferred it because of the experience of the American pilots who had fought off Soviet interceptors in the night skies and bad weather during General Freeman’s raid on Pyongyang. The American pilots, including Frank Shirer, had confirmed a long-held NATO article of faith: When it came to instrument flying with all visuals ruled out, American, British, and German fighters could outstrip their Russian counterparts.

Even during the daytime dogfights over northwestern Germany and over the area still held by NATO in the south around Mannheim and Heidelberg, the NATO fighters, particularly British and German Tornadoes and American F-111s and Falcon-18s, were outclassing the opposition. The problem was that the opposition had more planes and more pilots: an advantage of three to one in aircraft, two to one in pilots. It was a situation worsened by the spectacular success of the Soviet divisions in southern Germany, which had so badly mauled the Fourth Allied Tactical Air Force, SPETS attacks having penetrated as far as Bitburg, where forty-seven of the seventy-two F-15s based there were destroyed on the ground by “activated” SPETS groups who had easily infiltrated the sea of refugees fleeing westward from the Soviet juggernaut.

In Hannover, northeast of the Dortmund-Bielefeld pocket, the concern of the Soviet-Warsaw Pact was how to crush the pocket before NATO convoys could hope to replace what had been lost on the battlefields of Germany.

For the Soviet military accountants and logistical wizards in Berlin’s subterranean headquarters, the problem was never calculated in terms of pain, of lives lost, because already the human face had become obscured beneath the wrap of high technology. Modern technology, contrary to public opinion, had not made killing any less barbaric, the twisted metal of modern munitions wreaking as much hacking and butchering as any of the barbaric wars of old. One of the “advances” in technology was bullets so heavy, yet so small — made of depleted uranium — and of such velocity that upon impact, they could vaporize a man’s head in the way a piece of shell might have in the great artillery barrages of the First and Second World Wars.

For the HQ computer staffs, however, divisions were rectangles moved about on the computer screens, not a torso torn asunder, where arms and legs or stomachs simply disappeared and where carrion crows grew fat on the spilt innards of soldiers. Nor did the statisticians deal with the effect on morale of supersonic fighter attacks, or laser-guided antitank rockets, of the unimaginable nightmare of a cluster bomb bursting, bombs within bombs within bombs, releasing needle-sharp shrapnel. Nor did the statisticians deal with the overwhelming sweet stench of dead flesh that greased the treads of the tanks and APCs as men drove until they were exhausted or their fuel had been expended, many of them becoming nothing more than whimpering shadows of their former selves, their eyes bright with madness from high-tech stress levels beyond bearing.

In the Berlin bunkers, where the state had long held precedence over the individual, the Soviet military statisticians, many of them women, saw none of this — their job to coldly, dispassionately, estimate Allied losses and a timetable for Allied resupply. Bad weather to them was neutral; perhaps it would make the convoy safer, harder to find by visual means — on the other hand, the low mist and rolling fog banks of late fall could impede attack and aid defense on the land. For now, it was the matter of the convoys that Supreme Soviet Commander Marshal Leonid Kroptkin was concentrating upon. So long as the NATO fighter screen held over Western Europe, NATO supply lines through France and through Austria, if Vienna threw in its lot with the NATO forces, would sustain the Dortmund-Bielefeld pocket. And if supplies kept coming, the pocket could expand into counterattack. And so the top priority for Moscow and Berlin was to stop the convoys now heading for the French ports, from Dunkirk to Calais in the north to as far southwest as Dieppe, Saint-Malo, and Cherbourg.

“As long as this situation holds,” the Soviet Western Theater of Operations C in C reported, “we have not won the war.” It was not only the Allied submarine-escorted convoys that the marshal worried about, but the Allied capacity to airdrop supplies into the pocket if the NATO convoys succeeded in bringing in enough men and materiel to the ports. What the Russian commander wanted was massive reinforcements from the East preceded by an awesome artillery barrage of a thousand guns of the kind that had finally destroyed the Wermacht and swallowed up Berlin over fifty years ago. His losses had been staggering, the Allies exacting a terrible price, over 130,000 Russians killed while punching the hole through the Fulda Gap, and almost 200,000 Soviet troops wounded.

“There is talk of reserves coming up from Yugoslavia, Marshal,” his aide, a colonel, reminded him, pointing on the wall to the alpine border between northern Yugoslavia and southern Austria. “Through the Ljubljana Gap and—”

“Yes, there is talk,” said the marshal. “There is always a lot of talk, Colonel. And what if Austria does not come over to us and permit the Yugoslavs to pass through?”

“I think they will.”

“Yes, now,” said the marshal. “If it looks as if we are winning.” He turned to the huge, three-dimensional contour table map, his hand sweeping down over southern Germany to Austria. “No, my friend — the Austrians are stuffing themselves full of pastries, eyes darting like parrots west to east, waiting. Their friends are whoever wins. No one can wait for the Austrians.”

“The Yugoslavs could simply push their way through. Whether Austria liked it or not,” proffered the aide.

The marshal was bending over the contour map, his finger tracing the long fold of the Danube valley eastward to the conjunction of Czechoslovakia and Austria. “I thought you went to officers’ school. You should know better than to indulge in such speculation. If the Yugoslavs come in, they will first have to get through the Ljubljana Gap if they are to be any use to us.”

A dispatch rider, goggles and uniform splattered in mud, came in, saluted, and handed the marshal a list of the latest positions of the retreating Dutch forces in Westphalia, north of the Ruhr. The marshal nodded and told the rider to give the report to his logistics aide. The colonel, though distracted for a moment by the sight of the dispatch rider in a room buzzing and crackling with state-of-the-art electronic communications, returned to the subject of possible reinforcements confronting NATO’s southern flank. “Even if the Italians attacked on our southern flank, I doubt whether they could stop the Yugoslavs, Marshal,” the ambitious colonel pressed on.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Rage of Battle»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Rage of Battle» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Rage of Battle» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.