Ian Slater - Warshot

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian Slater - Warshot» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

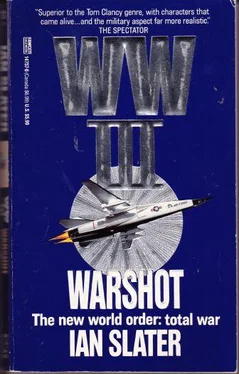

- Название:Warshot

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:0-449-14757-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Warshot: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Warshot»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The counterstrike: Unleash the brilliantly unorthodox American General Douglas Freeman. If this eagle can’t whip the bear and the dragon, no one can…

Warshot — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Warshot», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“David Brentwood. Guy you used on Ratmanov’s here somewhere in Khabarovsk.”

“Where in Khabarovsk?”

“I don’t know exact—”

“Well, find him, Dick. Tell him to get a team together— men he’s worked with before — I don’t want any screwups. Use Army Lynx helos to fly NOE. I want that SAS/D team in and out — fast. Tell them to rescue as many of our guys as possible and bring them straight to me. Try to get me the battery commander if possible so I can shoot the son of a bitch myself.”

Norton was already making notes and issuing orders for the best NOE — nap of the earth — Lynx chopper pilots in the division even as the “tote” board above Freeman’s HQ’s radio row was going crazy with blipping red lights, each the size of a glowing cigarette tip and representing a ChiCom regimental advance of over two thousand men, the “reds” outnumbering the stationary “blues,” the U.S. regiments, ten to one.

“What a screwup!” opined a radio operator, giving up his seat to his replacement, indicating the unofficial but widespread assessment of the situation.

“Shut up!” It was the duty officer reprimanding him.

Freeman held up his hand to intervene. “You got a complaint, soldier?”

The radio operator, who hadn’t realized the general was nearby, visibly gulped. “Complaint… no, sir.”

“Yes you have. We’ve got most of our divisions on Baikal’s west shore to stave off a Siberian violation of the cease-fire, and instead I get hit on the southern flank by the Chinese. Well, son, you’ve got every right to be mad. So am I.”

“Yes, sir.”

Freeman, putting his arm around the operator, steered him toward the coffee urn. “Tell you fellas something else…” Everyone was listening. “I’m gonna change that. Right about now.”

“Yes, General.”

With that, Freeman ordered alternate divisions — every second division on the Baikal line — pulled out to head southeast to block the Chinese advance on his southern flank, and ordered AIRTAC strikes against the ChiCom divisions to hold them off long enough “until the alternate divisions from Baikal can reach the Chinese and attack! We’re going to turn that goddamn ‘yellow peril’ into chop suey!”

The surge in morale that the general’s words produced was palpable in the HQ hut, and Norton shook his head at the duty officer, smiling in admiration of Freeman’s ability to so quickly raise the spirits of his troops. Freeman called Norton over. The general was still grinning, but his words told a different story. “Tell Washington I want every reserve, every ounce of gas, every bullet they’ve got, and I want it over here pronto. I know we can’t do it all by airlift, but get those big C-7s started, Dick. And get ‘em moving those convoys out from Pearl and the West Coast. I smell a big fucking rat — and his name’s Yesov. If that son of a bitch violates the cease-fire at Baikal, we’ll have a two -front war on our hands.” He paused, Norton noting that he was short of breath. “Any sign of him moving, Dick?”

“No, sir.” Norton indicated the met board. “There’re blizzard conditions around Baikal, anyway.”

“He could still move, Dick. Visibility or not. Besides, the temperature’s rising. Doesn’t feel like it, I know — but it is. Ice is starting to break up. Besides, blizzard’s only thing that can stop our air force, laser bombs and all. Not even the Stealths can laser designate targets in that lot.”

“I don’t think he’ll attack, General.”

“By God, I hope you’re right, Dick. Two-front war east and south. Our backs to the sea. Be a goddamn nightmare.”

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Between Irkutsk, forty miles west of Lake Baikal, and the lake, in the village of Bol’shaya Rechka, a babushka wrapped her black scarf tightly around her head before she stepped out on her porch. As she stooped to grasp the two splintery pine sticks that stood up from the frozen paper cups of milk, she heard a squeaking noise that reminded her of her youth on the communes: tractors starting the harvest. Then, the giant, Popsicle-like milks at her side, she stood transfixed, staring through the thick white curtain of falling snow, the enormous shapes becoming more distinct by the second — armor — tanks and enormous field guns, their weight on bipods atop the biggest tractor tracks she’d ever seen. They were all around her, albino leviathans, crawling inexorably eastward toward Lake Baikal. After a while the old peasant woman stopped counting.

Each of the more than three hundred three-man-crewed Siberian T-72M main battle tanks — an APSDS, armor-piercing-fin-stabilized discarding sabot round, in its big 125mm gun — stopped seven miles from the western shore on the southern end of the four-hundred-mile-long, banana-shaped lake. The tank regiment’s overall komandir, General Minsky of the Tenth Guards “Slutsk” Division, had at last been given the task he craved: his orders to spearhead the attack and defeat the Americans. He was eager but tense, his head tank regiment, with ninety-three of the “Slutsk” guards’ division’s 328 main battle tanks, assigned to undertake zadacha dnia —a total rout in the American sector in the southwestern Baikal. And the zadacha dnia had to be completed in no less than twenty-four hours, before the Americans could recover and regroup.

Minsky’s initial artillery/tank attack in his sector would be followed by what Yesov had declared would be a merciless presledovatelnyi boi —a pursuit of lightning savagery — designed to finish off the retreating Americans on the ice before they reached the relative safety of the taiga twenty miles across the lake from the small town of Port Baikal. And following Minsky, ready to spread out north and south of him after his blitzkrieg, were the remainder of the four thousand tanks, advancing on a forty-eight-mile, or eighty-kilometer, front, the maximum that anyone like Yesov, trained at the Frunze Academy, felt comfortable with.

Immediately behind Minsky’s ninety-three-tank spearhead came the regiment’s forty-six BMPs — armored personnel carriers — with higher velocity and harder-hitting thirty-millimeter guns replacing the old seventy-three millimeters, and behind them the regiment’s eighteen self-propelled 120mm, thirteen-mile-range guns, and the BM-21 multiple rocket launchers, forty tubes to each launcher.

The Slutsk division’s artillery regiment of nine self-propelled S-3 152mm guns was kept as far back as possible, while up front Yesov had his self-propelled howitzers, their crews so razor-sharp that it would take them only seven minutes — under half the time required for the towed guns — to have the guns fully emplaced and ready for firing. These self-propelled howitzers were the new M-1974s, amphibious versions of the old M-1973, 152mm, 360-degree-rotation howitzer. Their drive sprockets, while well-protected — being located forward and beneath the sloping glacis plate — nevertheless squeaked like the unoiled rail cars of the Trans-Siberian, which, a few miles back on Minsky’s right, or southern, flank, were even now hauling the supplies toward the lake, including a full range of main battle-tank 125mm HE, APDS, and HESH — heat, squash head — ammunition.

The babushka, now back inside her small bungalow, the wood-carved fretwork beneath the snow-filled window boxes shuddering like something alive, watched fearfully as the entire advance came to a halt. For a moment she could hear only the noise of mournful howling of the blizzard driving itself against the already snow-laden birch forest, but then she saw something that completely mystified her as the armored personnel carriers, with their blunt, bargelike snouts, advanced in line through the columns of main battle tanks and self-propelled artillery and, obeying flag signals— Yesov having banned any radio transmits — slowly turned left, northward, in unison, like a long line of prehistoric monoliths issuing forth enormous billowing clouds of thick, flour-white smoke into the white purity of the blizzard.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Warshot»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Warshot» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Warshot» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.