“Tell them to hold fire!”

From their place on the floor, Peter found himself staring directly at Michael, hidden beneath one of the tables. His eyes grew very wide. “Peter—”

“I mean it,” Peter told the man, pressing the barrel deeper. “Yell it, so everyone can hear.”

The man had relaxed in his arms. Peter felt him shudder, though not with pain. The man had started to laugh.

“Stand down!” a new voice said—a woman’s. “Everybody cease fire!”

The second man wasn’t a man after all. She was sitting on the floor with her back braced against one of the booths, her right arm held across her chest to clutch her wounded shoulder.

“Flyers, Peter.” Alicia drew her bloodied hand away. Now she was laughing, too. “Lucius, can you believe he fucking shot me?”

62

At the base of the ladder, Amy touched the map to her torch. The paper caught instantly, snatched away in a flash of blue flame. She doused the torch in the trickle of water at her feet, ascended the ladder, and shoved the manhole cover aside.

She was in the alley behind the apothecary shop. She sealed the plate and peeked around the corner of the building; above the heart of the city, the Dome stood imperiously, its hammered surface shining with light. She drew down her veil and walked briskly from the alleyway. Men with dogs were moving along the barricades. She strode up to the guardhouse, where two men were blowing on their hands, and displayed her pass.

“This doesn’t look right.” He showed it to the second man. “Does this look right to you?”

The col glanced at it quickly, then looked at Amy. “Lift your veil.”

She did as he asked. “Is there something wrong?”

He studied her face a moment. Then he handed back the pass. “Forget it. It’s fine.”

Amy threaded past them and headed up the stairs. None of the other men paid her any note; the guards at the gate had verified her presence as warranted. Inside, she marched past the guard at the desk, who barely glanced at her, crossed the lobby to the elevator, and rode it to the sixth floor.

The elevator opened on a circular balcony circumscribing the building’s atrium. Four corridors led away, like spokes on a wheel. Amy made her way around the balcony to the third corridor and down its length to the last door, where the guard, a droopy-faced man with a tonsure of gray hair, was sitting on a folding metal chair, flipping through the brittle pages of a hundred-year-old magazine. On the cover was the image of a woman in an orange bikini, her hands pushed upward through her hair.

“The Director asked to see me,” Amy told him, drawing up her veil.

His eyes broke from the page, finding Amy’s, and that was all it took. She eased him to the floor, propped his back against the wall, and took the key from his belt. His chin was rocked forward onto his chest. She put her lips close to his ear.

“I’m going to go inside now. I want you to count to sixty—can you do that?”

His eyes were closed. He nodded slightly, making a murmur of assent.

“Good. Count to sixty, and when you get there, throw yourself off the balcony.”

She unlocked the door and stepped inside. There was something deceptively benign about the room. Two wingback chairs faced an enormous desk, its polished surface gleaming faintly. The floor was covered in thick carpet, muffling everything but the sound of Amy’s breathing. One whole wall was books; another displayed a large painting, lit by a tiny spotlight, of three figures sitting at a long counter and a fourth man in a white hat, all seen through a window on a darkened street. Amy paused to read the small plaque at the base of its frame: Edward Hopper, Nighthawks , 1942.

To her right was a pair of parlor doors with windows of leaded glass. Amy turned the knob and eased through.

Guilder was lying on top of the blankets in his underwear. A pile of cardboard folders floated in the sea of bedding beside him. Soft, windy snores were issuing from his nose. Where should she stand? She chose the foot of the bed.

“Director Guilder.”

He jerked violently awake, darting a hand beneath his pillow. He pushed himself up the headboard, scrambling away from her; with both hands he leveled the pistol at her and cocked the hammer. He was trembling so profoundly Amy thought he might shoot her by accident.

“How did you get in here?”

She sensed his uncertainty. The robe of an attendant, but the face was none he knew. “The guard was very accommodating. Why don’t you put that down?”

“Goddamnit, who are you ?”

She heard voices from the hall, fists pounding on the outer door.

“I am Sergio,” she said. “I’ve come here to surrender.”

XI. THE DARKEST NIGHT OF THE YEAR

63

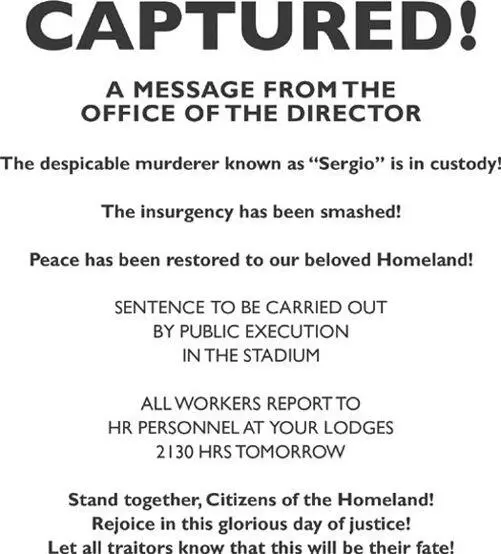

Events had followed just as Amy had foreseen. The time and place of her execution were set; only the method had yet to be revealed—the final detail on which their plan depended. Would Guilder simply shoot her? Hang her? But if such a meager display was all he intended, why had he ordered the entire population, all seventy thousand souls in the Homeland, to observe? Amy had baited the hook; would Guilder take it?

Peter passed the next four days lurching between emotional poles—alternating states of worry and astonishment, both overlain with a powerful feeling of déjà vu. Everything possessed a striking familiarity, as if no time had passed since they’d faced Babcock on the mountaintop in Colorado. Here they all were, together once more, their fates drawn together as if by a powerful gravitational force. Peter, Alicia, Michael, Hollis, Greer: they had converged upon this place by different routes, for different reasons. Yet it was Amy, once again, who had led them.

Greer had related the story of her transformation: Houston, Carter, the Chevron Mariner ; Amy’s journey into the bowels of the ship and then her return. The full measure of what had passed between Amy and Carter, Greer couldn’t tell them; all he knew was that Carter had directed them here. Beyond that, Amy either wouldn’t or couldn’t say.

That night at the orphanage, the two of them standing at the door, the tips of their fingers colliding in space: had she known what was happening to her? And had he? Peter had felt in Amy’s touch the pressure of something unstated. I am going away. The girl you know will not be here when next we meet . Which she had; the girl who Amy was had gone away. In her place was now a woman.

The group clothed their anxieties in unnecessary repetitions of their various preparations. The cleaning of weapons. The examination of blueprints and maps. The going over of checklists and the assorted mental inventories they would carry into war. Hollis and Michael became, in the last days, a kind of closed loop; their purpose had narrowed to Sara and Kate. Alicia dealt with the anxiety the way she dealt with everything—by pretending it wasn’t important. The bullet from Peter’s pistol had missed the bone and exited cleanly, a lucky thing, but even so. She would be healed in a day or two, but in the meantime the sling on her arm was a constant reminder to Peter of how close he’d come to killing her. When she wasn’t barking orders, she retreated into unreachable silence, letting Peter know, without saying so, that she had entered the zone of battle. Greer intimated that something had happened to her in the cell, that she’d been beaten badly, but any attempt to ask her more about this, to offer comfort, was sternly rebuffed. “I’m all right,” Alicia said with a peremptory tone that could only mean she wasn’t. “Don’t worry about me. I can take care of myself.” She seemed, in fact, to be actively avoiding him, disappearing for long stretches; if he didn’t know better, he would have said she was angry with him. She would return hours later smelling of horse sweat, but when Peter asked her where she’d gone, all she would say was that she’d been scouting the perimeter. He had no reason to doubt this, yet the explanation felt thin, a cover for something unstated.

Читать дальше