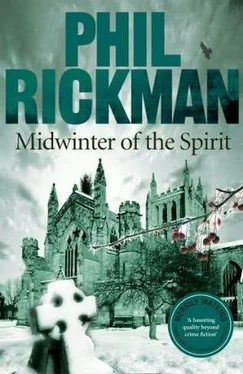

Phil Rickman - Midwinter of the Spirit

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Phil Rickman - Midwinter of the Spirit» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1999, ISBN: 1999, Издательство: Corvus, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Midwinter of the Spirit

- Автор:

- Издательство:Corvus

- Жанр:

- Год:1999

- ISBN:978-0-85789-017-7

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Midwinter of the Spirit: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Midwinter of the Spirit»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Midwinter of the Spirit — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Midwinter of the Spirit», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Pretty much like Christianity, in fact.’ Merrily lit a cigarette.

‘No, that’s bollocks.’ Jane shook her head furiously. ‘The Church is like: Oh, you don’t have to know anything; you just come along every Sunday and sing some crappy Victorian hymns and stuff and you’ll go to heaven.’

‘Jane, we’ve had this argument before. You just want to reduce it to—’

‘And anybody steps out of line, it’s: Oh, you’re evil, you’re a heretic, you’re an occultist and we’re gonna like burn you or something! Which was how you got the old witch-hunts, because the Church has always been on this kind of paternalistic power trip and doesn’t want people to search for the truth. Like it used to be science and Darwinism and stuff they were worried about, now it’s the New Age because that’s like real practical spirituality . And it’s come at a time when the Church is really feeble and pathetic, and the bishops and everybody are shit scared of it all going down the pan, so now we get this big Deliverance initiative, which is really just about… about suppression .’ Jane sat back in her chair with a bump.

‘Wow,’ Merrily said.

‘Don’t.’

‘What?’

‘You’re gonna say something patronizing. Don’t .’ Jane snatched back the leaflet and folded it up again. Evidence obviously. ‘I bet you were mega-flattered when Mick offered you the job, weren’t you? I bet it never entered your head that they want people like you because you’re quite young and attractive and everything, and like—’

‘It did, actually.’

‘Like you’re not going to come over as some crucifix-waving loony, what?’

‘It did occur to me.’ Merrily cupped both hands around her cigarette; she wasn’t sure if they allowed smoking in here. ‘Of course it did. It’s still occurring to me. Not your let’s-stamp-out-the-New-Age stuff, because I can’t quite believe that. But, yeah, I think he does want me for reasons other than that I’m obviously interested in… phenomena, whatever. Which is one reason I haven’t yet said yes to the job.’

Jane blinked once and they sat and stared at one another. Merrily thought about all the other questions that were occurring to her. And what Huw Owen had said to them all as they gathered outside the chapel in the last minutes of the course.

Maybe you should analyse your motives. Are you doing this out of a desire to help people cope with psychic distress? Or is it in a spirit of, shall we say, personal enquiry? Think how much deeper your faith would be if you had evidence of life after death. How much stronger your commitment to the calling if you had proof of the existence of supernatural evil. If that’s the way you’re thinking, you need to consider very carefully after you leave here. And then, for Christ’s sake, forget this. Do something else .

Merrily dragged raggedly on her cigarette.

‘You really want it, though, don’t you?’ Jane said. ‘You really, really want it.’

‘I don’t know,’ Merrily lied.

Jane smiled.

‘I have a lot of thinking to do,’ Merrily said.

‘You going to tell Mick you’re in two minds?’

‘I think I shall be avoiding the Bishop for a while.’

‘Ha.’ Jane was looking over her mother’s left shoulder.

Merrily said wearily, ‘He just came in, didn’t he?’

‘I think I’ll leave you to it. I’ll go and have a mooch around Waterstone’s and Andy’s. See you back at the car at six?’

The waitress arrived with the tea.

‘The Bishop can have mine if he likes,’ Jane said.

4

Moon

IT WAS WHAT happened with the crow, after the rain on Dinedor Hill. This was when Lol Robinson actually began to be spooked by Moon.

As distinct from sorry for Moon. Puzzled by Moon. Fascinated by Moon.

And attracted to her, of course. But anything down that road was not an option. It was not supposed to be that kind of relationship.

Most people having their possessions carried into a new home would need to supervise the operation, make sure nothing got broken. Moon had shrugged, left them to get on with it, and melted away into the rain and her beloved hill.

There really wasn’t very much stuff to move in. Moon didn’t even have a proper bed. When the removal men had gone, Lol went up to the Iron Age ramparts to find her.

He walked up through the woods, not a steep slope because the barn was quite close to the flattened summit where the ancient camp had been, the Iron Age village of circular thatched huts. Nothing remained of it except dips and hollows, guarded now by huge old trees, and by the earthen ramparts at the highest point.

And this was where he found Moon, where the enormous trees parted to reveal the city of Hereford laid out at your feet like an offering.

Lol was aware that some people called the hill a holy hill, though he wasn’t sure why. He should ask Moon. The ancient mysteries of Dinedor swam in her soul.

She was standing with her back to him, next to a huge beech tree which still wore most of its leaves. Her hair hung almost to the waist of the long medieval sort of dress she wore under a woollen shawl.

Making Lol think of drawings of fairies by Arthur Rackham and the centrefolds of those quasi-mystical albums from the early seventies – the ones which had first inspired him to write songs. The kind of songs which were already going out of fashion when Lol’s band, Hazey Jane, won their first recording contract.

Moon would still have been at primary school then. She seemed to have skipped a whole generation, if not two. Hippy nouvelle . Down in the city, she sometimes looked pale and nervy, distanced from everything. Up here she was connected.

Dick Lyden, the psychotherapist, had noticed this and given his professional blessing to Moon’s plan, despite the fears of her brother Denny, who was jittery as hell about it. ‘ She can’t do this. You got to stop her. SHE CANNOT LIVE THERE! OUT OF THE FUCKING QUESTION! ’

But she was a grown woman. What were they supposed to do, short of getting her committed to a psychiatric hospital? Lol, who’d been through that particular horror himself, was now of the opinion that it should never happen to anyone who was not dangerously insane.

When he first saw Moon on the ramparts, even though her face was turned away, he thought she’d never seemed more serene.

She glanced over her shoulder and smiled at him.

‘Hi.’

‘OK?’

‘Yes.’ She turned back to the view over the city. ‘Wonderful, isn’t it? Look. Look at the Cathedral and All Saints. Isn’t that amazing?’

From here, even though they were actually several hundred yards apart, the church steeple and the Cathedral tower overlapped. The sky around them was a strange, burned-out orange.

Moon said, ‘Many of the ley-lines through other towns, you can’t see them any more because of new high-rise buildings, but of course there aren’t any of those in Hereford. The skyline remains substantially the same.’

Lol realized he’d seen an old photograph of this view, taken in the 1920s by Alfred Watkins, the Hereford gentleman who’d first noticed that prehistoric stones and mounds and the medieval churches on their sites often seemed to occur on imaginary straight lines running across the landscape. Most archaeologists thought this was a rubbish theory, but Katherine Moon was not like most archaeologists. ‘It’s at least spiritually valid,’ she’d said once. He wasn’t sure what she meant.

‘Moon,’ he said now, ‘why do some people call it a holy hill?’

She didn’t have to think about it. ‘The line goes through four ancient places of worship, OK? Ending at a very old church in the country. But it starts here, and this is the highest point. So all these churches, including the Cathedral, remain in its shadow.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Midwinter of the Spirit»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Midwinter of the Spirit» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Midwinter of the Spirit» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.