Phil Rickman - A Crown of Lights

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Phil Rickman - A Crown of Lights» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: Corvus, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Crown of Lights

- Автор:

- Издательство:Corvus

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:978-0-85789-018-4

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Crown of Lights: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Crown of Lights»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Crown of Lights — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Crown of Lights», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Betty closed her eyes. It had been her decision. She’d turned from the east to face the north: a witch’s altar was always to the north. There was no turning back... was there?

When she reopened her eyes, she was facing the whitewashed north wall, where a document hung in a thin, black frame.

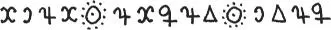

Betty looked at it, breathed in sharply. The breathing came hard. The air around her seemed to have clotted. She stared at the symbols near the bottom of the frame.

And saw, with an awful sense of déjà vu:

She felt almost sick now, with trepidation. There was nothing coincidental about this.

At the top of the document, under the funeral black of the frame, was something even more explicit.

ABRACADABRA

ABRACADABR

ABRACADAB

ABRACADA

ABRACAD

ABRACA

ABRAC

ABRA

ABR

AB

A

Betty spun away from the wall, snatched up one of the leaflets about the church and ran outside.

Under the Zeppelin cloud, she opened the leaflet to a pen-and-ink drawing of the church and a smaller sketch of the Archangel Michael with wings outstretched and a sword held above his head.

Under the drawing of the church, she read:

‘... the Abracadabra charm, dated from the seventeenth century, purported to have been used to exorcize a young woman. Heaven knows what she went through, but it sheds an interesting light on the state of faith in Radnorshire at the time.’

Betty stilled herself with a few minutes of chakra breathing, then went back into the church and up to the document itself, again leaving the door open for light.

What she’d read was a transcript of the original charm produced, it said in a tiny footnote, by an expert from the British Museum. The original was at the bottom: a scrap of paper with the ink faded to a light brown and now virtually indecipherable. There were no details about exactly how or when it had been found in the church.

But there was no inglenook fireplace where a box might be placed.

Hands clenched in the pockets of her ski jacket, Betty read the transcript. The two charms might be a century or more apart, but the similarities were obvious.

In the name of the Father, Son and of the Holy Ghost Amen X X X and in the name of the lord Jesus Christ I will delive Elizabeth Loyd from all witchcraft and from all Evil Spirites and from all evil men or women or wizardes or hardness of heart Amen X X X

It went on with a mixture of Roman Catholic Latin – pater noster, ave Maria – and cabbalistic words of power like ‘Tetragrammaton’, the name of God. At the bottom were two rows of planetary symbols. The sun, the moon and Venus were obvious. The one that looked like a ‘4’ was Jupiter.

Wizards... spirits... hardness of heart . All too similar. Another solid link, apart from St Michael, between the two churches.

There was more obsessive repetition:

I will trust in the Lord Jesus Christ my Redeemer and Saviour from all evil spirites and from all other assaltes of the Devil and that he will delive Elizabeth Loyd from all witchcraft and from all evil spirites by the same apower as he did cause the blind to see, the lame to walke and that thou findest with unclean spirites to be in thire one mindes amen X X X as weeth Jehovah Amen. The witches compassed her abought but in the name of the lord i will destroy them Amen X X X X X X X

It was signed by Jah Jah Jah.

Poor Elizabeth Loyd. A ‘young woman’. How old?

Twenty? Seventeen? Was she really possessed by evil? Or was she schizophrenic? Or, more likely, simply epileptic?

Heaven knows what she went through, but it sheds an interesting light on the state of faith in Radnorshire at the time.

Had it been carried out here, in the church? If so, Betty wasn’t picking up anything. What kind of minister had mixed this bizarre and volatile cocktail of Anglicanism, Roman Catholicism, paganism, cabbalism and astrology?

Or was it the local wise man, the conjuror?

Or were they one and the same?

Betty was glad the charm lay behind glass, that she wouldn’t have to force herself to touch it, where it had been held by the exorcist, didn’t even like to look too hard at the original manuscript, was glad that the ink had faded to the colour of soft sand.

She walked back outside into the churchyard and was drawn back – felt she had no choice – to that spot amongst the graves where she’d previously felt the weight of something. She wondered what had happened if, after the exorcism, the epilepsy or whatever persisted? There was something deeply distasteful about the whole business – and there had probably been villagers at the turn of the eighteenth century who also found it disturbing. But they’d have to keep quiet. Especially if the exorcism was performed by the minister.

She was gazing out towards the Forest – yellowed fields, a wedge of conifers – when the pain came.

It was so sudden and so violent that she sank to her knees in the long, wet grass, both hands at her groin. There was an instant of shocking cold inside her, and then it was over and she was crawling away, sobbing, to the shelter of a nearby gravestone.

She stayed there for several minutes, her breathing rapid and her heart rate up. She pushed her hair back out of her eyes and found that it was soaked with sweat.

When she was able to stand again, she was terrified there might be physical damage.

She stumbled back to the church wall and, trembling, wrote a huge banishing pentagram, clockwise on the air.

And then followed it with the sign of the cross.

20

Blessed Beneath the Wings of Angels

BEEN A WHILE since he was here last, but it might as well have been yesterday. Nothing changed, see. A new bungalow here, a fancy conservatory there. A few new faces that started out bright and shiny and open... and gradually closed in, grew cloudy-eyed and worried.

Like this boy in the pub. Londoner, sounded like. Gomer had seen it before. They came with their catering certificates and visions of taking over the village inn and turning it into a swish restaurant with fiddly little meals and vintage wine, fifty quid a time. Year or so later, it was back to the ole steak pie and oven chips and a pint of lager – three diners a night if they was lucky, at a fiver apiece.

Gomer sucked the top off his pint of Guinness. Ole Hindwell, he thought, where city dreams comes to die.

‘Not seen you around before,’ the London boy said.

‘That’s on account you en’t been around yourself more’n a week or two,’ Gomer told him.

‘Two years, actually. Two years in March.’ The boy had dandruffy hair, receding a bit, greying a bit. You could tell those two years had felt to him like half a lifetime. He’d be about forty years old; time to start getting anxious.

‘Bought the place off Ronnie Pugh, is it?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Ar.’ Gomer nodded, spying the creeping damp, already blackening walls they must have rewhitewashed when they moved in. ‘Tryin’ to get rid for six year or more, ole Ronnie.’

‘So it appears,’ the boy said, regrets showing through like blisters.

As well they might. Never fashionable, the Forest. No real old money, see. Radnorshire always was a poor county: six times as many sheep as people, and you could count off the mansions on one hand. Not much new money, neither: the real rich folk – film stars, pop stars, stockbrokers, retired drug dealers and the like – went to the Cotswolds, and the medium-rich bought theirselves some rambling black and white over in Herefordshire.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Crown of Lights»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Crown of Lights» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Crown of Lights» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.