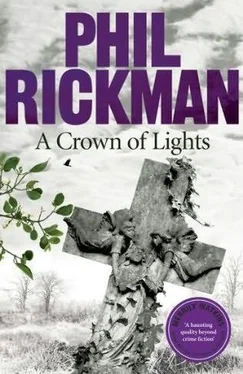

Phil Rickman - A Crown of Lights

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Phil Rickman - A Crown of Lights» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: Corvus, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Crown of Lights

- Автор:

- Издательство:Corvus

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:978-0-85789-018-4

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Crown of Lights: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Crown of Lights»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Crown of Lights — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Crown of Lights», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I think, somehow...’ Merrily looked into the cigarette smoke, ‘it makes the kind of sense neither of us is clever enough to explain.’

‘And I’m not going to try too hard to explain it now,’ she said to the congregation. ‘I think people in this job can sometimes spend too long trying to explain too much.’

In the pew next to Gomer, Jane nodded firmly.

‘I mean, I could go on about those watches ticking day and night under the ground, symbolizing the life beyond death... but that’s not a great analogy when you start to think about it. In the end, it was Gomer making the point that he and Minnie had something together that can’t just be switched off by death.’

‘Way I sees it, vicar, by the time them ole watches d’stop ticking, we’ll both be over this – out the other side.’ Gomer had pushed both hands through his aggressive hair. ‘Gotter go on, see, ennit? Gotter bloody go on.’

‘Yeah.’

‘What was it like when your husband... when he died?’

‘A lot different,’ Merrily said. ‘If he hadn’t crashed his car we’d have got divorced. It was all a mistake. We were both too young – all that stuff.’

‘And we was too bloody old,’ Gomer said, ‘me and Min. Problem is, nothin’ in life’s ever quite... what’s that word? Synchronized. ’Cept for them ole watches. And you can bet one o’ them buggers is gonner run down ’fore the other.’

Gomer smoked in silence for a few moments. He’d been Minnie Seagrove’s second husband, she’d been Gomer’s second wife. She’d moved to rural Wales some years ago with Frank Seagrove, who’d retired and wanted to come out here for the fishing, but then had died, leaving her alone in a strange town. Merrily still wasn’t sure quite how Minnie and Gomer had first met.

Gomer’s mouth opened and shut a couple of times, as if there was something important he wanted to ask her but he wasn’t sure how.

‘Not seen your friend, Lol, round yere for a while,’ he said at last – which wasn’t it.

‘He’s over in Birmingham, on a course.’

‘Ar?’

‘Psychotherapy. Had to give up his flat, and then he got some money, unexpectedly, from his old record company and he’s spent it on this course. Half of him thinks he should become a full-time psychotherapist – like, what mental health needs is more ex-loonies. The other half thinks it’s all crap. But he’s doing the course, then he’s going to make a decision.’

‘Good boy,’ Gomer said.

‘Jane still insists she has hopes for Lol and me.’

Gomer nodded. Then he said quickly, ‘Dunno quite how to put this, see. I mean, it’s your job, ennit, to keep us all in hopes of the hereafter: ’E died so we could live on, kinder thing – which never made full sense to me, but I en’t too bright, see?’

Merrily put out her cigarette. Ethel, the cat, jumped onto her knees. She plunged both hands into Ethel’s black winter coat.

The big one?

‘Only, there’s gotter be times, see, vicar, when you wakes up cold in the middle of the night and you’re thinkin’ to youself, is it bloody true ? Is anythin’ at all gonner happen when we gets to the end?’

From the graveside there came no audible ticking as Minnie’s coffin went in. Gomer had accepted that his nephew, Nev, should be the one to fill in the hole, on the grounds that Minnie would have been mad as hell watching Gomer getting red Herefordshire earth all over his best suit.

Walking away from the grave, he smiled wryly. He may also have wept earlier, briefly and silently; Merrily had noticed him tilt his head to the sky, his hands clasped behind his back. He was, in unexpected ways, a private person.

Down at the village hall, he nudged her, indicating several tea plates piled higher with food than you’d have thought possible without scaffolding.

‘Give ’em a funeral in the afternoon, some of them tight buggers goes without no bloody breakfast and lunch. ’Scuse me a minute, vicar, I oughter ’ave a word with Jack Preece.’ And he moved off towards a ravaged-looking old man, whose suit seemed several sizes too big for him.

Merrily nibbled at a slice of chocolate cake and eavesdropped a group of farmer-types who’d separated themselves from their wives and didn’t, for once, seem to be discussing dismal sheep prices.

‘Bloody what-d’you-call-its – pep pills, Ecstersee, wannit? Boy gets picked up by the police, see, with a pocketful o’ these bloody Ecstersee. Up in court at Llandod. Dennis says, “That’s it, boy, you stay under my roof you can change your bloody ways. We’re gonner go an’ see the bloody rector...” ’

‘OK, Mum?’

Merrily turned to find Jane holding a plate with just one small egg sandwich. Was this anorexia, or love?

‘What happened to Eirion, flower?’

‘He had to get home.’

‘Where’s he live exactly?’

‘Some gloomy, rotting mansion out near Abergavenny. It was quite nice of him to come, wasn’t it?’

‘It was incredibly nice of him. But then... he is a nice guy.’

‘Yeah.’

Merrily tilted her head. ‘Meaning he’d be more attractive if he was a bit of a rogue? Kind of dangerous?’

‘You think I’m that superficial?’

‘No, flower. Anyway, I expect he’ll be going to university next year.’

‘He wants to work in TV, as a reporter. Not – you know – Livenight .’

‘Good heavens, no.’

‘So you’re going to do that after all then?’ Jane said in that suspiciously bland voice that screamed hidden agenda .

‘I was blackmailed.’

‘Can I come?’

Merrily raised her eyes. ‘Do I look stupid?’

‘See, I thought we could take Irene. He’s into anything to do with TV, obviously. Like, he knows his dad could get him a job with BBC Wales on the old Taff network, but he wants to make his own way. Which is kind of commendable, I’d have thought.’

‘Very honourable, flower.’

‘Still, never mind.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Sure. You told that – what was her name? Tania?’

‘Not yet.’

‘She’ll be ever so pleased.’

And Jane slid away with her plate, and Merrily saw Uncle Ted, the senior churchwarden, elbowing through the farmers. He was currently trying to persuade her to levy a charge for the tea and coffee provided in the church after Sunday services. She wondered how to avoid him. She also wondered how to avoid appearing on trash television to argue with militant pagans.

‘Mrs... Watkins?’

She turned and saw a woman looking down at her – a pale, tall, stylishly dressed woman, fifty-fiveish, with expertly bleached hair. She was not carrying any food.

‘I was impressed,’ she said, ‘with your sermon.’ Her accent was educated, but had an edge. ‘It was compelling.’

‘Well, it was just...’

‘... from the heart. Meant something to people. Meant something to me, and I didn’t even know... er...’

‘Minnie Parry.’

‘Yes.’ The woman blinked twice, rapidly – a suggestion of nerves. She seemed to shake herself out of it, straightened her back with a puppet-like jerk. ‘Sister Cullen was right. You seem genuine.’

‘Oh, you’re from the hospital...’

‘Not exactly.’ The woman looked round, especially at the farmers, her eyes flicking from face to florid face, evidently making sure there was nobody she knew within listening distance. ‘Barbara Buckingham. I was at the hospital, to visit my sister. I think you saw her the other night – before I arrived. Menna Thomas... Menna...’ Her voice hardened. ‘Menna Weal.’

‘Oh, right. I did see her, but...’

‘But she was already dead.’

‘Yes, she was, I’m afraid.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Crown of Lights»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Crown of Lights» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Crown of Lights» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.