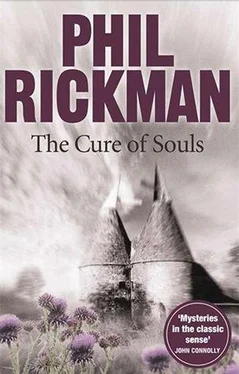

Phil Rickman - The Cure of Souls

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Phil Rickman - The Cure of Souls» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: Corvus, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Cure of Souls

- Автор:

- Издательство:Corvus

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:978-0-85789-019-1

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Cure of Souls: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Cure of Souls»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Cure of Souls — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Cure of Souls», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Any evidence of that?’

‘Of sexual activity? Apparently not. When there was nothing in the forensic evidence, nothing from the post-mortem, to suggest Stewart had recently had sex, they panicked and one of them changed his story – claiming they’d come here to do the business and found him already dead.’

‘That couldn’t have helped them,’ Merrily said.

‘Finished them completely, far as the jury was concerned. Found guilty, sent down for life. They’ve appealed now – every one appeals. Couple of civil-liberties groups assisting. Probably won’t succeed, but I imagine one or two people in the area are getting a touch jittery about it. We certainly are.’ He laughed nervously. ‘If they didn’t do it, who did? It’s one thing to live in a place where a murder was committed; something else to live with the possibility that the murderer’s still out there.’

‘You think that’s a real possibility?’

‘Oh yes.’

He walked over to the wall, pulled down a wooden pole with a slender sickle on one end. Unexpectedly, the crescent blade flashed in the shaft of sunlight from the middle window. Merrily stayed very still as he hefted it from hand to hand.

‘They used these things for cutting down bines. I sharpened it. I thought, they’re not going to get me like they got Stewart. Ridiculous.’ He shuddered, replaced the tool. ‘I just don’t trust the countryside.’

So why hadn’t the Stocks sold the place and got out?

‘I don’t understand. Why would anyone want to get to you? ’

‘I—’ He looked at her, as if he was about to say something, then he hung his head. ‘I don’t really know. I just don’t feel safe here. Never have. Lie awake sometimes, listening for noises. Hearing them, too. The country is—’

‘What sort of noises?’

‘Oh – creaks, knocking. Birds and bats and squirrels.’ He shrugged uncomfortably. ‘I don’t know. Nothing alarming, I suppose. Except for the footsteps. I do know what a footstep sounds like.’

‘You’ve actually heard footsteps?’

‘Not loud crashing footsteps echoing all over the place, like in the movies. These are little creeping steps. Always come when you’re half asleep. It’s like they’re walking into your head. You think you’ve heard them, though you’re never sure. But in the middle of the night, thinking is… quite enough, really.’

It wasn’t quite enough for Merrily. ‘What about the furniture being moved?’

He looked up sharply. ‘Oh, we didn’t hear that happen. We had the table over the bloodstained flag – to cover it, keep it out of sight. We’d come down in the morning and find it was back where… where it is now. This happened twice. But we never heard anything.’

‘And you talked about a figure? You said in the paper you’d seen a figure coming out—’

‘Yeah.’ He walked over to the part of the wall opposite the door. ‘Coming out… just here. I said “a figure” because you’ve got to make it simple for these crass hacks – my working life’s been about avoiding big words. But actually it was simply a… a lightform. Do you know what I mean?’

‘A moving light?’

‘A luminescence. Something that isn’t actually shining but is lighter than the wall. And roughly the shape of a person. We’d finished supper… a very late supper; it was our wedding anniversary. And sudenly the room went cold – now that happened, that’s one cliché that did happen. It’s a funny sort of cold, you can’t confuse it with the normal… goes right into your spine… do you know what I mean?’

‘Yes, I do.’ This was, on the whole, convincing. When you thought of all the embellishments he might have added – the familiar smell of Stewart’s aftershave, that kind of stuff…

Merrily shivered again, glad she’d put a jacket on – to hide the Radiohead T-shirt, actually. She’d left the vicarage in a hurry – no breakfast, just a half-glass of water – throwing her vestment bag into the boot. Usually, she’d spend an hour or so in the church before a Deliverance job, but there’d been no time for that either.

‘Mind you, it’s so often like a morgue in here.’ Gerard Stock folded his arms. ‘And dark in itself creates a sense of cold, doesn’t it? The living room through there’s no better. That was formerly the part where the dried hops were bagged up, put into sacks.’

‘Hop-pockets,’ Merrily said.

‘Oh, you know about hops?’

‘A bit.’

‘Stewart had absolutely steeped himself in the mythology of hops – not that there’s much of one. He got quite obsessed over something that—I mean, it’s just an ingredient in beer, isn’t it? A not very interesting plant that you have to prop up on poles.’

‘There was a hop-yard at the back here?’

‘ Was . The wilt got it.’

‘Is that still happening?’

‘I believe there are new varieties of hop, so far resistant to it. But it happened here.’

‘You said you saw lights out in the hop-yard.’

‘My wife. My wife saw them. I never have. That was the first thing that happened. It was soon after we moved in. Winter. Just after dusk. We’d brought in some logs for the stove, and she was standing in the doorway looking down the hill towards the hop-yard and she said she saw this light. A moving light. Not like a torch – more of a glow than a beam. Hovering and moving up and down among the hop-frames – appearing in one place and then another, faster than a human being could move. She wasn’t scared, though. She said it was rather beautiful.’

‘Just that once?’

‘No. I suppose not. After a while we didn’t—This might sound unlikely to you, but we stopped even mentioning those lights. When far worse things were happening in the house itself, I suppose unexplained lights in the old hop-yard seemed comparatively unimportant.’

‘Hops,’ Merrily said. ‘When you say Stewart was obsessed by hops, you mean from an historical point of view, or what?’

‘Well, that too, obviously. But also hops themselves. I wouldn’t claim to understand what he saw in them. To me, they’re messy, flakey things, not even particularly attractive to look at. But when we first took possession of the house, the walls and the ceiling were a mass of them: all these dusty, crumbling hop-bines – twelve, fifteen feet long – and the whole place stank of hops. I mean, I like a glass or two of beer as much as anyone, but the constant smell of hops… no, thank you. And when you opened a door, they’d all start rustling. It was like—’ He shook his head roughly.

‘Go on.’

‘Like a lot of people whispering, I suppose. Anyway, we cleared out the bines. It felt as though they were keeping even more light out of the place. Some of them were straggling over the windows. The windows in the living room back there once looked out down the valley. Apparently.’

Through the central window in here she could see blue sky. Through the other two, blue paint. It probably hadn’t even been this dark when it was a functioning kiln with a brick furnace in the centre.

‘The barns,’ she said.

He nodded.

‘That’s awful,’ Merrily agreed, ‘but I’m afraid it’s not—’

‘Your problem. No.’

‘Have you talked to a solicitor?’

‘I’ve talked to a lot of people,’ Mr Stock said.

‘Erm – that aroma of hops.’ Merrily breathed in slowly, through her nose. ‘I almost expected you to say you’d been smelling it again.’

She thought his eyes flickered, but it was too dim to be sure. He shook his head. ‘No, nothing like that.’

‘So… what about your wife?’

He was silent. His face seemed to have stiffened.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Cure of Souls»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Cure of Souls» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Cure of Souls» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.