“I phoned William and he said that he would find out who was in charge of the CF trial and get back to me, he hoped by the end of the day. Then I phoned Kasia on her mobile, but she was engaged, presumably still chatting to her family, although by now her phone credit would have run out and it must be them phoning her. I knew that she was going to meet some Polish friends from church, so I thought I’d tell her when she got back. When we’d know who was behind it all and she’d be safe.”

I n the meantime, I went to meet Mum at Petersham Nursery to choose a plant for your garden, as we’d arranged. I was glad of the distraction; I needed to do something rather than pace the flat waiting for William to ring me.

Kasia had been on at me again to lay flowers at the toilets building for you.

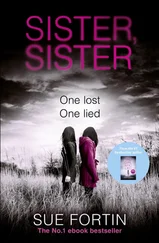

She’d told me I’d be putting my “odcisk palca” of love onto something evil. ( Odcisk palca is “fingerprint,” the nearest translation we could find, and a rather lovely one.) But that was for other people to do, not me. I had to find that evil and confront him head on, not with flowers.

After weeks of cold and wet, it was the first warm dry day of early spring, and at the nursery camellias and primroses and tulips were unfolding into color. I kissed Mum and she hugged me tightly back. As we walked, under the canopy of old greenhouses, it was as if we’d stepped back in time and into a stately home’s garden.

Mum checked plants for frost hardiness and repeat flowering while I was preoccupied—after searching for almost two months, by the end of the day I should know who killed you.

For the first time since I’d arrived in London, I felt too warm and took off my expensive thick coat, revealing the outfit underneath.

“Those clothes, they’re awful, Beatrice.”

“They’re Tess’s.”

“I thought they must be. You have no money at all now?”

“Not really, no. Well some, but it’s tied up in the flat until it’s sold.”

I have to own up that I had been wearing your clothes for quite a while. My New York outfits seemed ludicrous outside that lifestyle, besides which I’d discovered how much more comfortable yours are. It should have felt odd, and definitely serious, to be wearing my dead sister’s clothes, but all I could imagine was your amusement at seeing me in your hand-me-downs of hand-me-downs, me who had to have the latest designer fashion, who had outfits dry-cleaned after one wearing.

“Do you know what happened yet?” asked Mum. It was the first time she’d asked me.

“No. But I think I will. Soon.”

Mum reached out her fingers and stroked a petal of an early-flowering clematis. “She’d have liked this one.”

And suddenly she was mute, a paroxysm of grief passing through her body that looked unbearable. I put my arm around her but she was unreachable. For a while I just held her, then she turned to me.

“She must have been so frightened. And I wasn’t there.”

“She was an adult; you couldn’t have been with her all the time.”

Her tears were a wept scream. “I should have been with her.”

I remembered being afraid as a child, and the sound of her dressing gown rustling in the dark and the smell of her face cream, and how just the sound of her and the smell of her banished my fears, and I wished she’d been with you too.

I hugged her tightly, trying to make myself sound believable.

“She wouldn’t have known anything about it, I promise, nothing at all. He put a sedative into her drink, so she’d have fallen asleep. She wouldn’t have been afraid. She died peacefully.”

I had learned finally, like you, to put love before truth.

We carried on through the greenhouse, looking at plants, and Mum seemed a little soothed by them.

“So you won’t be staying much longer then,” she said. “As you’ll know soon.”

I was hurt that she could think I could leave her again, after this.

“No. I’m going to stay, for good. Amias has said I can stay in the flat, pretty much rent free I think.”

My decision wasn’t entirely selfless. I’d decided to train as an architect. Actually, I needn’t put that in the past tense; it’s what I still want to do when the trial is over. I’m not sure whether they’ll take me, or how I’ll fund it and look after Kasia and her baby at the same time, but I want to try. I know my mathematical brain, obsessed with detail, will do the structural side well. And I’ll search myself for something of your creative ability. Who knows? Maybe it’s lying dormant somewhere, an unread code for artistic talent wrapped tightly in a coiled chromosome waiting for the right conditions to spring into life.

My phone signaled and I saw a text from William wanting to meet, urgently. I texted back the address of the flat. I felt sick with anticipation.

“You have to go?” asked Mum.

“In a little while, yes. I’m sorry.”

She stroked my hair. “You still haven’t had a haircut.”

“I know.”

She smiled at me, still stroking my hair. “You look so like her.”

W hen I arrived home, William was waiting for me at the bottom of the steps. He looked up at me, his face was white, his usual open expression pinched hard with anxiety.

“I’ve found out who’s in charge of the cystic fibrosis trial at St. Anne’s. Can I come in? I don’t think we should be…”

His normally measured voice was rushed and uneven. I opened the door and he followed me inside.

There was a moment before he spoke. I heard Granny’s clock tick twice into the silence.

“It’s Hugo Nichols.”

Before I could ask any questions, William turned to me, his voice still quick, pacing now.

“I don’t understand. Why on earth has he been putting babies without cystic fibrosis in the trial? What the hell’s he been doing? I just don’t understand.”

“The CF trial at St. Anne’s has been hijacked,” I replied. “To test out another gene.”

“My God. How did you find that out?”

“Professor Rosen.”

“And he’s going to the police?”

“No.”

There was a moment before he spoke. “So it’ll be up to me then. To tell them about Hugo. I’d hoped it would be someone else.”

“It’s hardly telling tales, is it?”

“No. It’s not. I’m sorry.”

But I still couldn’t make sense of it. “Why would a psychiatrist run a genetic therapy trial?”

“He was a research fellow at Imperial. Before he became a hospital doctor. I told you that, didn’t I?”

I nodded.

“His research was in genetics,” continued William.

“You never said.”

“I never thought—my God—I just never thought it was relevant.”

“That was unfair of me. I’m sorry.”

I remembered William telling me that Dr. Nichols was rumored to have been brilliant and “destined for greatness,” but I’d thought the rumor must be wrong, believing instead my own opinion that he was scruffily hopeless. Remembering my view of Dr. Nichols, I realized that I’d dismissed him as a suspect not only because I’d thought him too hopeless to be violent, nor even because I’d thought he had no motive, but because of my entrenched belief that he was fundamentally decent.

William sat down, his face strained, his hands drumming the arms of the sofa. “I spoke to him about his research once, years ago now. He told me about a gene he’d discovered and that a company had bought it from him.”

“Do you know which company?”

“No. I’m not sure he even said. It was a long time ago. But I do remember some of what he said because he was so passionate, so different from how he usually is.” William was pacing again now, his movements jerky and angry. “He told me it had been his life’s ambition, actually no, he said it was his life’s purpose , to get his gene into humans. He said he wanted to leave his fingerprint on the future.”

Читать дальше