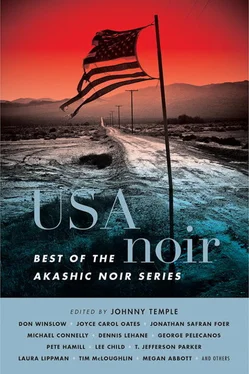

Johnny Temple - USA Noir - Best of the Akashic Noir Series

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Johnny Temple - USA Noir - Best of the Akashic Noir Series» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Akashic Books, Жанр: Триллер, Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:USA Noir: Best of the Akashic Noir Series

- Автор:

- Издательство:Akashic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-61775-189-9

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

USA Noir: Best of the Akashic Noir Series: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «USA Noir: Best of the Akashic Noir Series»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

USA Noir: Best of the Akashic Noir Series — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «USA Noir: Best of the Akashic Noir Series», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And then a young man stepped up onto the edge of the field. He wore a bulky coat without a cap or a hood. His hand was inside the coat, and his smile was not the smile of a friend. There were silver caps on his front teeth.

I turned my back on him. Pee ran hot down my thigh. My knees were trembling, but I made my legs move.

The night flashed. I felt a sting, like a bee sting, high on my back.

I stumbled but kept my feet. I looked down at my blood, dotted in the snow. I walked a couple of steps and closed my eyes.

When I opened them, the field was green. It was covered in gold, like it gets here in summer, ’round early evening. A Gamble and Huff thing was coming from the open windows of a car. My father stood before me, his natural full, his chest filling the fabric of his shirt. His sleeves were rolled up to his elbows. His arms were outstretched.

I wasn’t afraid or sorry. I’d done right. I had the lottery ticket in my pocket. Detective Barnes, or someone like him, would find it in the morning. When they found me .

But first I had to speak to my father. I walked to where he stood, waiting. And I knew exactly what I was going to say: I ain’t the low-ass bum you think I am. I been workin’ with the police for a long, long time. Matter of fact, I just solved a homicide.

I’m a confidential informant, Pop. Look at me.

THE GOLDEN GOPHER

by Susan Straight

Nobody walked from Echo Park to Downtown. Only a walkin fool.

But in the fifteen years I’d lived in LA, I’d only met a few walkin fools. LA people weren’t cut out for ambulation, as my friend Sidney would have said if he were here. But the people of my childhood weren’t here. They were all back in Rio Seco.

The only walkin fools here were homeless people, and they walked to pass the time or collect the cans or find the church people serving food, or to erase the demons momentarily. They needed air passing their ears like sharks needed water passing their gills to survive.

But me—I’d been a walkin fool since I was sixteen and walked twenty-two miles one night with Grady Jackson, who was in love with my best friend Glorette. I’d been thinking about that night, because someone had left a garbled message on my home phone around midnight—something about Glorette. It sounded like my brother Lafayette, but when I’d listened this morning, all I heard was her name.

Grady Jackson and his sister were the only other people I knew from Rio Seco who lived in LA now, and I always heard he was homeless and she worked in some bar. I had never seen them here. Never tried to. That night years ago, when he stole a car, I’d wanted to come to LA, where I thought my life would begin.

But I had thought of Grady Jackson every single day of my life, sometimes for a minute and sometimes for much of the evening, since that night when I realized that we were both walkin fools, and that no one would ever love me like he loved Glorette.

I came out my front door and stepped onto Delta, then turned onto Echo Park Avenue. My lunch meeting with the editor of the new travel magazine Immerse was at one. I had drunk one cup of coffee made from my mother’s beans, roasted darker than the black in her cast-iron pan. When I went home to Rio Seco, she always gave me a bag. And I had eaten a bowl of cush-cush like she made me when I was small—boiled cornmeal with milk and sugar.

All the things I’d hated when I was young I wanted now. I could smell the still-thin exhaust along the street. It smelled silver and sharp this early. Like wire in the morning, when my father and brothers unrolled it along the fence line of our orange groves.

All day I would be someone else, and so I’d eaten my childhood.

When I got close to Sunset, I saw the homeless woman who always wore a purple coat. Her shopping cart was full with her belongings, and her small dog, a rat terrier, rode where a purse would have been. She pushed past me with her head down. Her scalp was pink as tinted pearls.

At Sunset, I headed toward Downtown.

Downtown, receptionists and editors always said, “Parking is a bitch, huh?” I always nodded in agreement—I bet it was a bitch for them. If someone said, “Oh my God, did you get caught up in that accident on the 10?” I’d shake my head no. I hadn’t.

And I never took the bus. Never. Walking meant you were eccentric or pious or a loser—riding the bus meant you were insane or masochistic and worse than a loser.

I had a car. Make no mistake—I had the car my father and brothers had bought me when I was twenty-two and graduating from USC. They wanted to make sure I came home to Rio Seco, which was fifty-five miles away. My father was an orange grove farmer and my brothers were plasterers. They drove trucks. They bought me a Chevy Corsica, and I always smiled to think of myself as a pirate.

I was like a shark too—or like the homeless people. I needed to walk every day, wherever I was, traveling for a piece or just home. I needed constant movement. And every time I walked somewhere, I thought of Grady Jackson. Now that I was thirty-five, it seemed like my mind placed those rememories, as my mother called them, into the days just to assure me of my own existence.

I’d have time in the Garment District before lunch. One thing about walkin fools—they had to have shoes.

I had on black low-heeled half-boots today, and flared jeans, and a pure white cotton shirt with pleats that I’d gotten in Oaxaca. It was my uniform, for when I had to move a long way through a city. Boots, jeans, and plain shirt, and my hair slicked back and held in a bun. Nothing flashy, nothing too money or too poor. A woman walking—you wanted to look like you had somewhere to go, not like you were rich and ready to be robbed, and not like a manless searching female with too much jewelry and cleavage.

Down Sunset, the movement in my feet and hips and the way my arms swung gently and my little leather bag bumped my side calmed me. My brain wasn’t thinking about bills or my brother Lafayette, who’d just left his wife and boys, or that Al Green song I’d heard last night that made me cry because no one would ever sing that to me now and slide his hands across my back, like the boys did when we were at house parties back in Rio Seco. When we were young. “ I’m so glad you’re mine ,” Al sang, and his voice went through me like the homemade mescal I’d tried in Oaxaca, in an old lady’s yard where only a turkey watched us.

No one I knew now, in this life, at all the parties and receptions and gallery openings, felt like that—like the boys with us back home, in someone’s yard after midnight. Throats vibrating close to our foreheads, hands sliding across our shoulder blades. Girl, just— Just lemme get a taste now. Come on.

When I was home lately, I had trouble working. I looked at old things like my mother’s clothespins and a canvas bag I used to wear across my shoulder when we picked oranges in my father’s grove.

But walking, I was who I had become—a travel writer everyone wanted to hire.

I’d written about the Bernese Oberland for Conde Nast , about Belize for Vogue , about Brooklyn for Traveler .

I passed vacant lots tangled with morning glories like banks of silver-blue coins, and the sheared-off cliffs below an old apartment complex, where shopping carts huddled like ponies under the Grand Canyon.

I looked at my watch. Eight forty-five. I smelled all the different coffees wending through the air from doughnut shops and convenience stores. Black bars were slid aside like stiffened spiderwebs. Every morning in late summer, my mother and I would brush aside the webs from the trees in our yard, the ones made each night by desperate garden spiders. Here, everyone was desperate to get the day started and make that money.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «USA Noir: Best of the Akashic Noir Series»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «USA Noir: Best of the Akashic Noir Series» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «USA Noir: Best of the Akashic Noir Series» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.