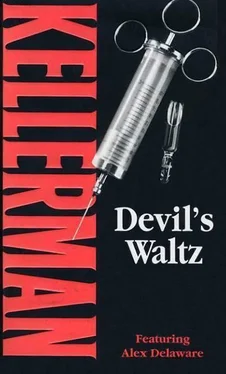

Jonathan Kellerman - Devil's Waltz

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jonathan Kellerman - Devil's Waltz» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Little Brown, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Devil's Waltz

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little Brown

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0-316-90289-2

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Devil's Waltz: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Devil's Waltz»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Devil's Waltz — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Devil's Waltz», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Okay, everyone,” she said. “If you’ll just file out one by one, the officer will check your ID and then you can go.”

“Yo,” said the black man. “Welcome to San Quentin. What’s next? Body searches?”

More tunes in that key, but the crowd started to move, then quieted.

It took me twenty minutes to get out the door. A cop with a clipboard copied my name from my badge, asked for. verifying identification, and recorded my driver’s license number. Six squad cars were parked in random formation just outside the entrance, along with an unmarked sedan. Midway down the sloping walkway to the parking structure stood a huddle of men.

I asked the cop, “Where did it happen?”

He crooked a finger at the structure.

“I parked there.”

He raised his eyebrows. “What time did you arrive?”

“Around nine-thirty.”

“P.M.?”

“Yes.”

“What level did you park on?”

“Two.”

That opened his eyes. “Did you notice anything unusual at that time — anyone loitering or acting in a suspicious manner?”

Remembering the feeling of being watched as I left my car, I said, “No, but the lighting was uneven.”

“What do you mean by uneven, sir?”

“Irregular. Half the spaces were lit; the others were dark. It would have been easy for someone to hide.”

He looked at me. Clicked his teeth. Took another glance at my badge and said, “You can move on now, sir.”

I walked down the pathway. As I passed the huddle I recognized one of the men. Presley Huenengarth. The head of hospital Security was smoking a cigarette and stargazing, though the sky was starless. One of the other suits wore a gold shield on his lapel and was talking. Huenengarth didn’t seem to be paying attention.

Our eyes met but his gaze didn’t linger. He blew smoke through his nostrils and looked around. For a man whose system had just failed miserably, he looked remarkably calm.

10

Wednesday’s paper turned the assault into a homicide.

The victim, robbed and beaten to death, had indeed been a doctor. A name I didn’t recognize: Laurence Ashmore. Forty-five years old, on the staff at Western Peds for just a year. He’d been struck from behind by the assailant and robbed of his wallet, keys, and the magnetized card key that admitted his car to the doctors’ lot. An unnamed hospital spokesperson emphasized that all parking-gate entry codes had been changed but admitted that entry on foot would continue to be as easy as climbing a flight of stairs.

Assailant unknown, no leads.

I put the paper down and looked through my desk drawers until I found a hospital faculty photo roster. But it was five years old, predating Ashmore’s arrival.

Shortly after eight I was back at the hospital, finding the doctors’ lot sealed with a metal accordion gate and cars stack-parked in the circular drive fronting the main entrance. An ALL FULL sign was posted at the mouth of the driveway, and a security guard handed me a mimeographed sheet outlining the procedure for. obtaining a new card key.

“Where do I park in the meantime?”

He pointed across the street, to the rutted outdoor lots used by nurses and orderlies. I backed up, circled the block, and ended up queuing for a quarter hour. It took another ten minutes to find a space. Jaywalking across the boulevard, I sprinted to the front door. Two guards instead of one in the lobby, but there was no other hint that a life had been snuffed out a couple of hundred feet away. I knew death was no stranger to this place but I’d have thought murder rated a stronger reaction. Then I looked at the faces of the people coming and going and waiting. Nothing like worry and grief to narrow one’s perspective.

I headed for the rear stairway and noticed an up-to-date roster just past the Information desk. Laurence Ashmore’s picture was on the top left Specialty in Toxicology.

If the portrait was recent, he’d been a young-looking forty-five. Thin, serious face. Dark, unruly hair, hyphen mouth, horn-rimmed eyeglasses. Woody Allen with dyspepsia. Not the type to pose much of a challenge for a mugger. I wondered why it had been necessary to kill him for his wallet, then realized what an idiotic question that was.

As I prepared to ride up to Five, sounds from the far end of the hospital caught my attention. Lots of white coats. A squadron of people moving across my line of sight, rushing toward the patient-transport elevator.

Wheeling a child on a gurney, one orderly pushing, another holding an I.V. bottle and keeping pace.

A woman I recognized as Stephanie. Then two people in civvies. Chip and Cindy.

I went after them and caught up just as they entered the lift. Barely squeezing in, I edged my way next to Stephanie.

She acknowledged me with a twitch of her mouth. Cindy was holding one of Cassie’s hands. She and Chip both looked defeated and neither of them glanced up.

We rode up in silence. As we got off the elevator Chip held out his hand and I grasped it for a second.

The orderlies wheeled Cassie through the ward and through the teak doors. Within moments her inert form had been lowered to the bed, the I.V. hooked up to a drip monitor, and the side rails raised.

Cassie’s chart was on the gurney. Stephanie picked it up and said, “Thanks, guys.” The orderlies left.

Cindy and Chip hovered near the bed. The room lights were off and slivers of gray morning peeked through the split of drawn drapes.

Cassie’s face was swollen, yet it appeared drained — an inflated husk. Cindy took her hand once more. Chip shook his head and wrapped his arm around his wife’s waist.

Stephanie said, “Dr. Bogner will be by again and so should that Swedish doctor.”

Faint nods.

Stephanie cocked her head. The two of us stepped out into the hall.

“Another seizure?” I said.

“Four A.M. We’ve been in the E.R. since then, working her over.”

“How’s she doing?”

“Stabilized. Lethargic. Bogner’s doing all of his diagnostic tricks but he’s not coming up with much.”

“Was she in any danger?”

“No mortal danger, but you know the kind of damage repetitive seizures can do. And if it’s an escalating pattern, we can probably expect lots more.” She rubbed her eyes.

I said, “Who’s the Swedish doctor?”

“Neuroradiologist named Torgeson, published quite a bit on childhood epilepsy. He’s giving a lecture over at the medical school. I thought, why not?”

We walked to the desk. A young dark-haired nurse was there now. Stephanie wrote in the chart and told her, “Call me immediately if there are any changes.”

“Yes, Doctor.”

Stephanie and I walked down the hall a bit.

“Where’s Vicki?” I said.

“Home sleeping. I hope. She went off shift at seven, but was down in the E.R. until seven-thirty or so, holding Cindy’s hand. She wanted to stay and do another shift, but I insisted she leave — she looked totally wiped out.”

“Did she see the seizure?”

Stephanie nodded. “So did the unit clerk. Cindy pressed the call button, then ran out of the room, crying for help.”

“When did Chip show up?”

“Soon as we had Cassie stabilized, Cindy called him at home and he came right over. I guess it must have been around four-thirty.”

“Some night,” I said.

“Well, at least we’ve got outside corroboration of the seizures. Kid’s definitely grand mal.”

“So now everyone knows Cindy’s not nuts.”

“What do you mean?”

“Yesterday she talked to me about people thinking she was crazy.”

“She actually said that?”

“Sure did. The context was her being the only one who saw Cassie get sick, the way Cassie would recover as soon as she got to the hospital. As if her credibility was suspect. It could have been frustration, but maybe she knows she’s under suspicion and was bringing it up to test my reaction. Or just to play games.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Devil's Waltz»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Devil's Waltz» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Devil's Waltz» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.