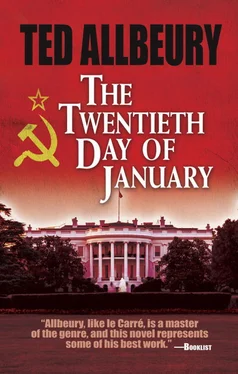

Ted Allbeury

THE TWENTIETH DAY OF JANUARY

This one is for Terry Kitson and John Sexton, with love.

THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION

ARTICLE XX

(Proposed March 1932; Adopted February 1933)

SECTION I

The terms of the President and Vice-President shall end at noon on the twentieth day of January, and the terms of Senators and Representatives at noon on the third day of January, of the years in which such terms would have ended if this article had not been ratified; and the terms of their successors shall then begin.

James Bruce MacKay sat with his feet up on the low coffee table, an open copy of Time magazine spread across his lap as he lit a cigarette. He waved out the match, tossed it into the ashtray and picked up the magazine again. He turned through the pages to the double spread entitled “People.” There was the usual picture of Shirley MacLaine, a piece about a defector from the Bolshoi, and a long paragraph about the author of another biography of Hemingway. As he turned to the book reviews the duty signals officer slid a typed sheet over the magazine pages. He read it slowly and carefully. Kowalski had been pulled off the plane at Warsaw airport and taken back into town. The four men who had taken him had been in plain clothes and had spoken Russian not Polish. He looked up at the signals captain.

“Where’s Anders?”

“Off duty, sir.”

MacKay reached in his pocket for a Biro and initialled the report. As he handed it back he said, “Get him in.”

He looked back at the magazine but the print was just a blur as he thought about Kowalski. It had happened two hours and forty minutes ago and by now he’d be unconscious. The interrogation team would have a drink and then there’d be an injection to bring him round for the next session. But that was going to be Anders’s worry, not his. He shook his head like a dog coming out of water and focused his eyes on the magazine pages.

Ten minutes later he tossed the magazine on to the coffee table and stood up, glancing at his watch as he stretched his arms. It was 01.30 hours on the first of November.

He walked over to the duty director’s bunk and started to undress. He heard the noise of a car door closing from down in the street. It was probably Anders arriving to sort out his problems in Warsaw. From the nearby Thames came the impatient blast of a boat’s siren. As he pulled the khaki blanket over his shoulder he could smell the ozone from the radio room and hear the agitated chatter of a Telex down the corridor.

James MacKay was an Edinburgh Scot with one of those neat, small-featured faces that never seem to grow old. Medium height, and slimly built, with a liking for bits and pieces of clothes rather than suits. But there was a flair to the clothes that he wore. The kind of flair that Parisiennes are said to have. Not that he was in any way effeminate; but in a calling where diplomats and civil-servants abounded, a shirt or shoes worn a little ahead of the general fashion could make a man noticed. Not with disapproval by any means, and perhaps it was more that he was remembered than noticed.

He had joined SIS straight from university at a time when universities were providing more problems for Special Branch than recruits. Like a graduate police constable, an eye was kept on him. With a father who was a banker and a mother who was a professional musician, his masters were never quite sure which set of genes was going to prove prepotent. And there were not all that many members of SIS who could mingle with undergraduates without changing their appearance.

It had been remarked, not necessarily with disapproval, that MacKay seemed to be seen with a whole series of pretty girls and it was put down to his charm. Even his male contemporaries agreed that MacKay had charm. And what they liked even more was that he seemed totally unaware of this attribute. He was as charming to men as he was to women. In a trade where cynicism and ruthlessness predominated, MacKay had proved exceptionally successful. A critical senior had once commented that a MacKay interrogation was more like old friends comparing notes than Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service pursuing the Queen’s enemies. But MacKay got results, and that was what counted.

It was nearly an hour later when he woke, and as he stood up he slid his arms into his jacket and shuffled through to the next room. It was empty, reeking of cigarette smoke and with the bare bulb still alight as it hung from the ceiling. The copy of Time was still there and he leafed through the first few pages to find the photograph. It was on here, under the headline “Gallup and Harris say it’s Powell.”

He sat down in the chair, shivering slightly from the cold. There were eight people in the photograph, all smiling into the camera, and the caption read: “With a 19 per cent lead in the polls, candidate Logan Powell and campaign manager Andrew Dempsey return to Hartford for the final days of the campaign.”

He bent forward and switched on the electric fire. If you saw a face in a magazine you assumed you recognized it because it was well known and familiar, a film star or some public figure. But that wasn’t why the photograph had stayed in his mind. He remembered Dempsey now.

It had been in Paris. May 1968. And the song had said it was the Dawning of the Age of Aquarius. But China had exploded her first atom bomb, France her first hydrogen bomb and the North Koreans had captured the first US Navy ship to be taken since 1807. And on the streets of Paris the students were demonstrating against the Government. That was where he had last seen Andy Dempsey, with bright red blood soaking his white shirt from a broken nose as they slung him into the black van.

After the taunting shouts, they had thrown cobbles from the streets at the police before the SDECE, with the black crosses on their white helmets, came in. It was they who had beaten up Dempsey, and his girl, as the barriers came down. Her mouth had been wide open as she screamed as the thug twisted her breast and kneed her groin. Then he had lost sight of her as she fell to the ground in the forest of feet and legs.

Dempsey was an American and his girl was a Russian or a Pole. He couldn’t remember which. That was the last time he had seen them. He had been withdrawn to London just afterwards. It had been one of his first jobs for SIS, a low-profile penetration of student groups in Paris. And Dempsey had been on his list as a member of the Communist Party and intimately involved with a Soviet citizen. His reports would still be on file.

He switched off the fire and went back to bed.

It was midday before he had time to go to Central Records. He sat in front of the micro-film reader for over an hour. There was more than he remembered. Apart from the typed reports there had been a handful of photographs and several pages of notes in his own handwriting. The round careful script looked naïve and juvenile now. He had forgotten about Kleppe.

He walked back to the house in Bessborough Street. It was one of those rambling turn-of-the-century houses that wealthy merchants built for themselves when cotton was still king but Manchester was beginning to lose the fight to London as the centre of trade. Now it was the operational base of one of those special units that were spawned from time to time by SIS. Highest security, but liable to be disbanded at any time. The present incumbents were designated as SF14. Special Force 14 were responsible for planning and mounting deep penetration operations into the intelligence services of the Soviet bloc. MacKay was one of its two operational directors.

Читать дальше