But that was four years ago. Turov’s status within Russia had changed since then.

“Andrei Turov’s semi-retired now, isn’t he?” Chris said. “I heard he sold his businesses and was living in the country. There were even rumblings of some big falling-out with Putin.”

“That’s the story, yes.” Martin’s lip quivered involuntarily. “You know how some men fake their own deaths? I think he may have faked this falling-out with Putin. We have intel that they met in February and March. And have had several phone conversations since.” The vertical lines returned to Martin’s brow. “I can’t go into all of it right here, except to say we’ve got one high-level asset in Russia, and signals intercepts supporting what she tells us.”

“And so, what—you’re saying there’s something I could do that America’s sixty-billion-dollar intelligence community can’t?”

Martin kept down a brief, conspiratorial smile. Chris’s former boss held an old-school belief in the power of the individual over the organization. He had issues with the restructuring of the intelligence community, which had tripled in size since 9/11 but continued to “miss” key events, as the media liked to point out, the rise of ISIS being one of the best known. “You remember you once told me, there’s weakness in numbers?”

“Did I?” Christopher liked the sound of that, though he didn’t remember saying it.

“That in certain cases, a team of four or five people, focused on a single objective, could do more than all seventeen IC agencies?” His eyebrows rose for emphasis. “Well, this is one of them. Although I’m not talking about a team of four or five at this point. Just you.”

“I see,” Chris said, not missing the qualifier at this point .

“We have a second source on this, in London. It’s someone you know. We think he may have something actionable on Turov. But he insists on giving it to you directly. That’s why I’m here.”

“Okay. You’re not talking about Max Petrenko, by any chance?”

“Yes, as a matter of fact.”

Now Chris smiled. Maxim Petrenko was a security “consultant” who’d made and lost a fortune during Russia’s Wild West era, the Yeltsin years; later, he’d managed one of Turov’s security firms. But he’d fled the country in 2011 or 2012 under a cloud of corruption charges after giving an indiscreet newspaper interview. Now he ran a small spy shop in London. His work mostly involved peddling information, Chris had heard, paying anonymous sources—drivers, security men, prostitutes—and selling what he learned to third parties, often Russian intelligence. He reminded Chris a little of a dirty drug dealer, who cut good information with bad. “Petrenko’s not entirely reliable, though, is he?”

“This is different,” Martin said. “Someone connected with Turov has given him something we think is credible. You could probably complete the deal in ten minutes.”

Christopher let his eyes drift to the beach, finding Anna, holding her book on her lap and gazing at the ocean. Ten minutes in London, maybe. But first I’d have to get there. And who knows where those ten minutes might lead? The late-morning breeze carried a breath of sea mist through the terrace screens. As Martin explained, Chris thought of the possible directions this day might have taken. But he also felt a gathering interest. Martin had known that just mentioning Turov’s name would produce this response.

“He’s agreed to meet with you in London tomorrow afternoon. It’s set up, actually.” Martin reached for his bag. “I’ve got your travel documents here.”

“Ah. You know how to spoil a man’s vacation.”

This time, Martin didn’t smile. He looked at Chris with anticipation, until it was clear to both of them that he would accept. Anna would be disappointed; but she wouldn’t object. Anna was a veteran diplomat, whose rivers of patience ran deeper than his. It was one of her talents to absorb setbacks without showing it. Also, Anna believed, as he did, in serving when called.

“What do you expect he’s going to tell us?”

“A name. Someone Turov’s dealing with. Hopefully a date. Whatever’s going to happen, it’s going to be soon, possibly within a week. He’s agreed to answer two questions. After that, it’s up to you.”

Christopher sighed, imagining how much Petrenko had billed Martin. But that wasn’t the point: if this really was Turov, the threat transcended cost, or any personal reservations he might have. Anna, he saw, was putting on her shirt and sandals, looking their way. “What do you think it’s about?”

Martin wrinkled his nose. “I go back to what you wrote in your report—Turov has this idea about a new, sophisticated kind of warfare. Something we won’t anticipate. It’s about a story: Russia’s going to tell a story. They’re going to make the world believe it, and repeat it. We have indications it will probably begin with a single event. Some sort of an attack.”

“An attack on us.”

“In some fashion. But not the kind of attack anyone in the administration will be looking for.” Anna had slung her bag over her shoulder and was walking in a steady, graceful rhythm over the sand.

“And what about this other thing—?” Chris said. “The signals intercepts?”

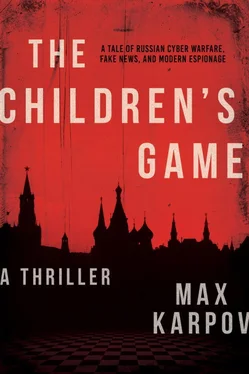

“There’s a phrase NSA has picked up. Something called ‘the children’s game.’ We know Turov also used it in a phone conversation with the president this spring.”

“Maybe just a reference to his grandchildren?”

“Probably not. We think it’s the event. That could be your second question. The payment transfer is done. Surveillance arranged. All you need to do is show up in the park.”

“Well, I’d prefer to pass on the surveillance,” Christopher said, more concerned that it would draw attention to Petrenko than to him.

Lindgren suddenly smiled broadly, and Christopher misunderstood, thinking he was smiling at what he’d just said. But then he saw: he was looking at Anna, who was standing in the arched entryway, letting her eyes adjust.

Martin leaned over to Christopher. “I hope she won’t be too angry with me,” he whispered.

Wednesday, August 11. London.

The meeting with Max Petrenko was scheduled for twenty past four in Holland Park. Petrenko ran his business now from a rented two-room office in upscale Mayfair. He was having trouble paying rent, the London case officer told Christopher, and might have to relocate at the end of the year. If Petrenko really knew something about Turov, as Martin believed, it was probably a fluke.

Christopher took a cab to Abbotsbury Road and walked into the park, stopping at a bench near the Japanese garden as instructed. For nine minutes he sat, glancing at the passersby. He was beginning to wonder if he’d chosen the wrong bench when he saw Petrenko marching up the path, dressed in an ill-fitting seersucker suit. For a moment Chris didn’t recognize him: the Russian had put on weight and his forehead appeared taller than he remembered. Petrenko seemed to miss him at first, walking past with swinging arms, then turning and pretending to do an elaborate double take. “Christopher Niles?”

Chris raised his eyebrows and stood. The pretense was two old acquaintances bumping into one another in the park. “Max.”

“My goodness. How long has it been?” They exchanged greetings over a lengthy handshake, and began to walk, Petrenko talking in his deep-throated broken English, gesturing with a familiar Russianness: balling his fingers and opening them dramatically. Telling Chris about the changes in Moscow since the late nineties when Petrenko had made his fleeting fortune there—his voice tensing up when he mentioned the current president, becoming more relaxed when the topic was Yeltsin. “I knew him, of course, years ago,” he said, meaning Putin. “In Leningrad. He was nothing then. A bureaucrat. But fiercely loyal. Later, he wanted me to travel with him. You can imagine how that would have ended.” Petrenko was talking almost like a ventriloquist now, his lips clenched and barely moving.

Читать дальше