‘They obviously dug.’

‘Dug?’

‘They found out a lot about you. When you were a kid you were a rebel, right?’

‘A lot of kids are.’

‘I guess it had something to do with your father.’

Talin frowned. Why should it? ‘My father?’

‘You were very fond of him?’

‘He died when I was twelve.’

‘Time enough to get very fond of him.’

‘I don’t follow you,’ Talin said.

‘It must have been a shock, the way… he… died.’

‘The way he died?’

‘Let’s not go into it,’ Massey said abruptly.

‘Let’s. He died from pneumoconiosis, the miners’ disease.’

‘According to the article,’ Massey said, ‘he died from radiation sickness.’

‘In a coal mine?’

‘In a cobalt mine.’

‘You’re crazy.’

‘Persecution didn’t end in 1953 with Stalin’s death,’ Massey said.

‘Are you saying he was killed deliberately?’

‘Many enemies of the State were given the choice of immediate execution or slow death in a cobalt mine.’

Icy calm, hands gripping the steering wheel, Talin asked: ‘What makes you think, what made this magazine think, that my father was guilty of a crime against the State?’

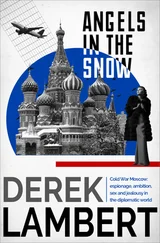

They were nearing the outskirts of Moscow. Tall apartment blocks loomed through the mist.

Massey said: ‘The magazine seemed to have access to a lot of information.’

‘With sources?’

‘I don’t see why they should have made it up.’

‘And what was my father supposed to have done?’

‘Protested, I guess. That was enough.’

‘Protested? Protested about what?’

‘About overcrowding, bad food in winter, conditions in the coal mine where he worked before he was sent to the cobalt mine… He was something of a rabble-rouser, your father. He was tried before No. 2 District People’s Court in Khabarovsk on 8 November 1962, before Judge Zina Orlova.’

‘And sentenced to death for protesting? Don’t give me that shit.’

Talin spun the wheel viciously. The Moskvich skidded round a corner. Talin drove into the skid, righting it.

Massey said: ‘He was accused of embezzling Government property. Stealing coal, maybe, who knows. Anyway they were determined to make an example of him. The charge carried the death penalty.’

‘And you took the word of a journalist about this?’

A pause. The mist was clearing. Talin could see an illuminated red star over the Kremlin.

Massey said softly: ‘No, I checked it out myself.’

‘Who with?’

‘Contacts. It’s all true, Nicolay.’

‘I don’t believe it. Why are you telling me this?’

‘I didn’t want to. But you should know the truth.’

‘My father would have told me the truth.’

‘I doubt it, Nicolay. Would you have told your son such a truth?’

‘I would have found out. Even if my mother hadn’t told me the other kids would have done.’ No, they moved us to Novosibirsk! ‘I don’t believe it,’ he shouted as he jammed his foot on the accelerator, as a motorcycle without rear lights cut across their path, as he braked, as the Moskvich skidded broadside across black ice and somersaulted over a snow-covered embankment.

Dyetsky Mir, the huge toyshop opposite Lubyanka Gaol and the KGB headquarters, was packed.

Gingerly, Robert Massey eased his way through the crowds. The rib cracked in yesterday’s automobile accident throbbed with pain and his body ached all over.

He discovered that the areas nearest the counters were the safest because there some orderliness prevailed. The shoppers had to line up while a salesgirl calculated their bill on an abacus; armed with the bill, they had to line up at a cash-desk; then they had to queue again to collect their purchases.

Massey was conscious of the cuts and bruises on his face but few Muscovites, intent on buying New Year gifts for their children, took any notice.

Exactly where Rybak would make contact hadn’t been stated. Massey skirted counters stacked with rag dolls, toy rifles consisting of a metal pipe, a slab of wood and a trigger, model rockets as primitive as the real Soviet hardware was refined.

The toys were crude, but did it matter? If a child was unaware of the sophisticated playthings of the West he was happy with these. And if Santa Claus was Grandfather Frost in silver robe and tinselled hat, so what?

‘You look as if you’ve been through a combine harvester,’ Rybak said. ‘What happened?’

Massey told him as the Ukrainian led him through the crowds; they parted before him like demonstrators facing a baton charge.

‘And Talin, how is he?’

‘A few bruises. We were lucky.’

‘He knows how to pilot a spaceship but he doesn’t know how to drive a car. Strange, isn’t it? What have you to report?’

Massey stopped at a counter and picked up a toy revolver, its butt jewelled with a plastic red star. ‘The launch is on 14 January.’ He pulled the trigger, nothing happened.

‘Is that all?’

‘At the next penetration they are going to programme our computers for an ASAT attack on one of our own satellites.’

‘ASAT?’

‘Anti-satellite device.’

‘Which satellite?’

‘Elint 23.’

‘Anything else?’

‘Tell them Phase Three has been accomplished.’

First hit, with devastating revelation, preferably personal.

The car was turning over and over; excited voices, hands pulling him out on to the snow.

‘Anything more?’

Massey shook his head. Nothing more except that I am destroying a man’s past and his future.

Rybak’s fingers gripped Massey’s arm. ‘I said the next meeting will have to be in Leninsk. What the hell’s the matter? Are you concussed?’

‘Where?’

‘There is a church beside the railroad a mile from the station to the west. Next Saturday. Six in the evening. But shake off your tail again. Did you have any trouble today?’

‘It was still misty. I lost him in Gorky Street.’

‘And now I shall lose myself, not an easy task when you’re my size.’

But he managed it easily enough.

One life destroyed but millions saved, Massey reminded himself; if, that was, everything Reynolds had told him was true.

Comforted, Massey made his way towards the main door of the store reflecting that, so far, road accidents apart, the campaign was proceeding smoothly. And it wasn’t until that evening that he heard that Talin had disappeared.

He had to know the truth.

To find it he had to reach Khabarovsk 4,000 miles east of Moscow and to get there he had to employ both guile and arrogance.

First the arrogance to by-pass travel restrictions. In his experience Soviet bureaucracy was so cumbersome that it could easily be toppled.

If he had been a peasant, a clerk or a factory hand it would have been difficult. But he was élite, a cosmonaut, a Hero, with the ID to prove it.

He went direct to the Aeroflot headquarters at 49/51 Leningrad Highway. At the booking counter a stout woman with lacquered blonde hair regarded him phlegmatically.

He told her that he wanted to fly to Khabarovsk. She reached for various forms but when he added: ‘Tonight,’ her hand stopped over the papers.

‘Impossible.’

‘No seats?’

She shrugged; it was impossible.

Knowing that Aeroflot would always throw a humble citizen off an aircraft to make way for a VIP or a tourist from the West, Talin showed her his ID.

She was impressed. Recognition flitted across her features. Nervously she patted her helmet of hair. ‘Even so it is impossible, Comrade Talin, because there is a delegation of geologists on the scheduled flight. There is no room.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу