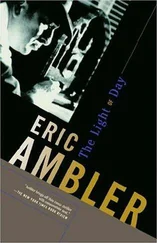

Eric Ambler - The Levanter

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eric Ambler - The Levanter» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: House of Stratus, Жанр: Шпионский детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Levanter

- Автор:

- Издательство:House of Stratus

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Levanter: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Levanter»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Levanter — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Levanter», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I don’t dislike my brothers-in-law; they are both worthy men, but one is a dentist and the other an associate professor of physics. Neither of them knows anything about business. Yet, while both would be understandably affronted if I offered to advise them in their professional capacities, neither has ever hesitated for a moment to tender detailed criticisms of, and advice about, the management of our company. They regard business, somewhat indulgently, as a sort of game which anyone with a little common sense can always join in and play perfectly. With the dreadful persistence of those who argue off the tops of their heads from positions of total ignorance, they would make their irrelevant points and formulate their senseless proposals while my sisters took it in turn to nod their idiotic heads in approval. Having to listen to these blithe fatuities was almost as exhausting as having later to dispose of them without being unforgivably offensive. No, I don’t dislike my brothers-in-law; but there have been times when I have wished them dead.

Their immediate and enthusiastic approval of my Syrian agreement was, therefore, both disconcerting and disquieting.

Giulio the dentist, who is Italian, became quite eloquent on the subject. “It is my considered opinion,” he said, “that Michael has been both statesmanlike and farsighted. Dealing with idealists, ideologues perhaps in this case, is no easy matter. In their minds all compromise is weakness, and negotiation a mere path to treason. The radical extremist of whatever stripe is consistently paranoid. Yet there are chinks even in their black armour of suspicion, and Michael has found the most vulnerable self-interest and greed. We have no need of gunboats to help us do our business. This agreement is the modern way of doing things.”

“Nonsense!” said my mother loudly. “It is the weak and shortsighted way.” She stared Giulio into silence before she turned again to me. “Why,” she continued sombrely, “was this confrontation necessary? Why, in God’s name, did we ourselves invite it? And why, having merely discussed an agreement, did we fall into the trap of signing it? Oh, if your father had been alive!”

“The agreement is not signed, Mama. I have only initialled a draft.”

“Draft? Hah!” She struck her forehead sharply with the heel of her hand, a method of demonstrating extreme emotion that did not disturb the careful setting of her hair. “And could you now disavow that initialling?” she demanded. “Could you now let our name become a byword in the marketplace for vacillation and bad faith?”

“Yes, Mama, and no.”

“What do you say?”

“Yes to the first question, no to the second. A draft agreement initialled is a declaration of intent. It is not absolutely binding. There are ways of pulling out if we wish to. I don’t think we should, but not for the reasons you give. There would be no question of bad faith, but it might well be thought that we had been bluffing. In that case we could not expect them to deal generously with us in the future.”

“But it was you, Michael, who took the initiative. Why? Why did you not wait passively until the time was ripe to employ those tactics which your father knew so well?” She had leaned forward across the table and was rubbing the thumb and third finger of her right hand together. Her second diamond ring glittered accusingly.

“I have explained, Mama. We are dealing with a new situation and a different type of man.”

“Different? They are Syrians, aren’t they? What can be new there?”

“A distrust of the past, a real wish for reform and determination to bring about change. I agree that a lot of their ideas are half-baked, but they will learn, and the will is there. I may add that if I had attempted to bribe Dr. Hawa, or even hinted at the possibility, I would certainly have been in jail within the hour. That much at least is new.”

They are still Syrians, and new men quickly become old. Besides, how do you know that the parties to your agreement will still be there in six months’ time? You see a changed situation, yes. But remember, such situations can change more than once, and in more than one direction.’’

I removed my glasses and polished them with my handkerchief. My wife, Anastasia, has told me that this habit of mine of polishing my glasses when I want to think carefully is bad. According to her it produces an effect of weakness and confusion on my part. She may be right; I can always count on Anastasia to observe my shortcomings and to keep the list of them well up to date.

“Let me be clear about this, Mama.” I replaced the glasses and put the handkerchief away. “There are many in Damascus, persons of experience, who think as you do. I believe that if Father were alive he would be among them. I also believe that he would be wrong. I don’t deny the value of patience. But just waiting to see which way the cat is going to jump and wondering which palms will have to be greased may simply be a way of doing nothing when you don’t think it safe to trust your own judgment. By going to these people rather than waiting for them to decide our fate in committee, we have secured solid advantages. With luck, our capital there can be made to go on working for us.”

She shook her head sadly. “You have so much English blood in you, Michael. More, I sometimes think, than your father had, though how such a thing could be I do not know.” Coming from my mother these were very harsh words indeed. I awaited the rest of the indictment. “I well remember,” she went on steadily, “something that your father said in 1929. That was before you were born, when I was” — she patted her stomach — “when I was carrying you here. A British army officer had been staying in our house. An amateur yachtsman he was, and the yard had been doing some repairs to his boat. When he left he forgot to take with him a little red book he had been reading. It was a manual of infantry training, or some such thing, issued by the War Office. Your father read this book and one thing in it amused him so much that he read it aloud to me. ‘To do nothing,’ the War Office said, ‘is to do something definitely wrong’.” How your father laughed! ‘No wonder,’ he said, ‘that the British army has such difficulty in winning its wars!’.”

Only my brothers-in-law, who had not heard the story so many times before, laughed; but my mother had not finished yet.

“You, Michael,” she said, “have done things for which you claim what you call solid advantages. First advantage, compensation for loss of our Syrian businesses which we will not receive and which is therefore stolen from us. Second advantage, a license to subsidize with the stolen money, and much too much of your valuable time, some nonexistent industry producing nonexistent goods. Yes, we have the sole agency for these goods, if those peasants and refugees there can ever be made to produce them. But when will that be? If I know those people, not in my lifetime.”

She had, of course, put her finger unerringly on the basic weakness of the whole arrangement. I was to be reminded of that phrase about “nonexistent industry producing nonexistent goods” all too often during the months that followed. At the time all I could do was sit there and pretend to an unshaken calm that I certainly did not feel.

“Are there any questions?”

“Yes.” It was my sister Euridice. “What is the alternative to this agreement?”

“The alternative that Mama proposes. We do nothing. In my opinion this means that eventually we will have to cut our losses in Syria, write them off. The best we could hope for, I imagine, would be a counter-revolution there which would restore the status quo. I don’t see it happening myself, but …” I shrugged.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Levanter»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Levanter» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Levanter» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.