Alex Dryden

DEATH IN SIBERIA

To my god-daughter Daisy Bell

‘We’re not afraid to down nine shots of vodka,

Or eat cabbage pickled in permafrost.

For, you see, we’re the men,

We’re the men of the seventieth parallel’

An Arctic Siberian miner’s song

‘Trees completely ceased to grow. Grass withered. There were no animals. And no children were born.’

From a tale of the Evenki tribe in Arctic Siberia

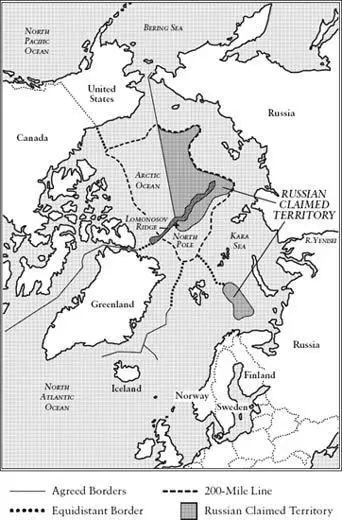

‘The Arctic is Russian’

Artur Chilingarov, Vladimir Putin’s Arctic exploration leader and a Russian parliamentary deputy, July 2007

Russian Claimed Territory in the Arctic Ocean

THE FOOTSTEPS BEHIND him seemed to be getting closer. To Gunther Bachman – or Herr Professor Gunther Bachman, to give him his full title – they had become a constant threat.

He heard the slap slap slap of the steps again now on the wet concrete of the Siberian street. Bachman’s reaction was a constriction in his heart, a shortness of breath. For in Gunther Bachman’s alternately declining and rising tide of panic, the steps had begun to seem like the approach of his own execution.

He’d read somewhere about false executions. In Vietnam, was it? No, it was Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. They were a particularly Oriental variation of cruelty, as Professor Bachman had understood it.

But that was what this torture of the footsteps in this Siberian city had become, as night began to fall like the lowered hood of the executioner himself. He may not have been strung up with a rope around his neck, only to be allowed to fall half-alive to the ground, as they’d done to their victims in Cambodia. But what was following him in the driving rain through the ever more obscure maze of streets contained the same terrifying promise.

He turned around another corner, blindly now, and into one more anonymous street. There was the same fragmented concrete, the rain sloshing off it in rivulets on to the trash-strewn roadway.

Here he saw a row of nineteenth-century, one-storey wood houses abutting the street, some with faded paint just visible where once it had been bright – greens and blues and even pink. The houses were tilting into the ground, cock-eyed like drunks, where the Siberian earth had frozen and thawed repeatedly for more than a century and slowly sucked them into its bottomless maw.

Bachman walked on past the once pretty houses. But their strange, crooked angles seemed sinister to him now. Like something from a middle European fairy tale where the faded beauty of a woman turns out to be the harbinger of death.

And no matter how much he wanted to, he dared not look back.

The steps behind him were so close now he thought that he could hear panting. Or was it his own breath? It sounded like the panting of something inhuman that was tracking him and had been since he’d left the airport.

He patted the sides of his coat with both hands, as if he were looking for something in the pockets. His dark-blue, water-streaked raincoat from Karstadt in Munich’s Kaufinger Street swished in the downpour.

He quickened his pace. A choking noise came from his throat, and the thick, dangling craw of his turkey neck tightened against the collar of his shirt.

The brief fantasy of the civilised city of Munich – his city, his world – and the department store Karstadt where he’d bought the coat, momentarily gave him an illusion of calm; the memory of the smooth, silent elevators, the well-heeled customers, the bright lights, the friendly, caring faces of the store’s assistants, the shelves of reassuring consumer goods.

But all those comforting memories might as well have been a million miles away. He was here, not in Munich, not at home. He was walking the pitiless Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk. He was in a city where life had little or no meaning. A dead dog lay upended by a car and left in the broken street. A frozen tramp with a beard like Rasputin’s slumped on a corner, looking more like a drenched and shaggy animal than a human being; sets of aggressive eyes shone in the gathering gloom – the desperate, moneyless and addicts who would cut your throat for a kopeck. Out here in the industrial wasteland of Krasnoyarsk, Munich might as well have not existed.

He thought back to his last and recent encounter with a friendly human being. It had been earlier that day, up beyond the Arctic Circle, in the city of Norilsk from where he’d taken the flight this afternoon. In his miserable prefabricated hotel room in Norilsk on this very morning, Vasily’s man was sitting across from him on the edge of the bed. It was Vasily’s man who had told him only hours earlier how to conceal the documents he was carrying. ‘Take a spare pair of shoes with you. That way you can stash your own shoes,’ he had added by way of explanation. ‘And so hide what’s in them. Then if they stop you, you’re clean.’

But he hadn’t remembered – or had thought it superfluous – to buy another pair of shoes before he’d got on the plane at Norilsk, or when he’d stepped off the plane here in Krasnoyarsk from that hellish, slave-built city up beyond the Arctic Circle. And so he couldn’t stash what he was carrying in his shoes by removing them and hiding them in some anonymous locker – at the rail station, perhaps. That was what Vasily’s man had suggested, he now remembered, the rail station.

He shuddered. He knew he was out of his depth.

The self-pity soon returned, washing over him once more, as if the acid rain of the industrial city contained it.

He wasn’t trained for this. He wasn’t trained for the management of fear, or in the art of subterfuge. He was a scientist, a professor, a respected nuclear expert on the international stage. He wasn’t a spy. How had he got himself into this? How had he agreed to be the courier? How had he come to be carrying something so valuable? Why had Vasily passed on to him the documents via his go-between, and not to some other foreigner who could have taken them to safety – and to glory?

But as soon as these thoughts surfaced he realised it had been exactly that – personal glory – which had led him to accept the documents. It was his own over-arching ambition that had prompted him to take the documents from Vasily’s man. From what he had seen of them at the hotel, before they’d been sewn into his shoes, the documents were apparently so important that they would make his whole career, right at the twilight period of it. A Nobel prize awaited him, perhaps. That was what the documents portended. Professor Gunther Bachman, Nobel laureate.

But in his denial of the risks back then, sunk in the grim, empty hotel in Norilsk where he’d been told by the go-between that Professor Vasily Kryuchkov would not be meeting him, he had suppressed the fact that the documents were also something that the Russians would kill for.

His international colleague Professor Kryuchkov’s so-called ‘inability’ to meet him had been explained to Bachman by the go-between as the authorities’ prevention of their meeting. That should have been warning enough. It seemed that Vasily Kryuchkov was in any practical sense of the word a prisoner of his own people above the Arctic Circle. He was too valuable to be allowed out of the closed military area up there, let alone to meet anyone from the West. Bachman had been told as much, as he drained the last drink from the hotel mini-bar for courage and studied the documents. What Vasily Kryuchkov had discovered must never leave Russia. The warning came back to haunt him and it wasn’t his career he cared for any longer, Nobel laureate or not – it was his life.

Читать дальше