“Well, sooner or later,” Miscolo said, smiling. “Unless, of course, you don’t want any.”

“I’d like a family,” Redfield said.

“Nothing like it,” Miscolo answered, warming to his subject, “I’ve got two kids myself, a girl and a boy. My daughter’s studying to be a secretary at one of the commercial high schools here in the city. My son’s up at MIT. That’s in Boston, you know. You ever been to Boston?”

“No.”

“I was there when I was in the Navy, oh, this was way back even before the Second World War. Were you in the service?”

“Yes.”

“What branch?”

“The Army.”

“Don’t they have a base up near Boston someplace?”

“I don’t know.”

“Seems to me I saw a lot of soldiers when I was there.” Miscolo shrugged. “Where were you stationed?”

“How much longer will they be with her?” Redfield asked suddenly.

“Oh, coupla minutes, that’s all. Where were you stationed, Mr. Redfield?”

“In Texas.”

“Doing what?”

“The usual. I was with an infantry company.”

“Ever get overseas?”

“Yes.”

“Where?”

“I was in the Normandy invasion.”

“No kidding?”

Redfield nodded. “D-Day plus one.”

“That musta been a picnic, huh?”

“I survived,” Redfield said.

“Thank God, huh? Lotsa guys didn’t.”

“I know.”

“I’ll tell you the truth, I’m a little sorry I missed out on it. I mean it. When I was in the Navy, nobody even dreamed there was gonna be a war. And then, when it did come, I was too old. I’d have been proud to fight for my country.”

“Why?” Redfield asked.

“Why?” For a moment, Miscolo was stunned. Then he said, “Well…for…for the future.”

“To make the world safe for democracy?” Redfield asked.

“Yeah. That, and…”

“And to preserve freedom for future generations?” There was a curiously sardonic note in Redfield’s voice. Miscolo stared at him.

“I think it’s important my kids live in freedom,” Miscolo said at last.

“I think so, too,” Redfield answered. “Your kids and my kids.”

“That’s right. When you have them.”

“Yes, when I have them.”

The room went silent.

Redfield lit a cigarette and shook out the match. “What’s taking them so long?” he asked.

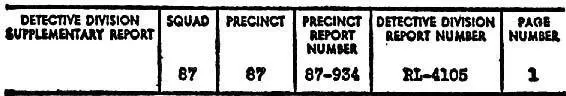

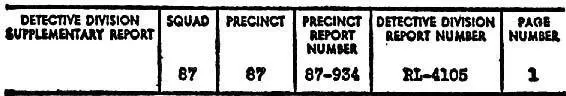

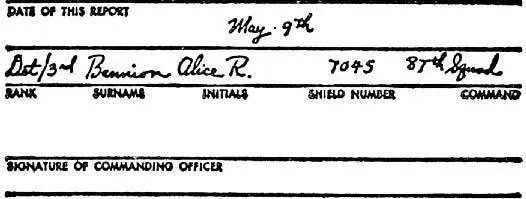

The policewoman who spoke privately to Margaret Redfield was twenty-four-years old. Her name was Alice Bannion, and she sat across the desk from Mrs. Redfield in the empty squadroom and listened to every word she said, her eyes saucer-wide, her heart pounding in her chest. It took Margaret only fifteen minutes to give the details of that party in 1940, and during that time Alice Bannion alternately blushed, turned pale, was shocked, curiously excited, repulsed, interested, and sympathetic. At 1:00, Margaret and Lewis Redfield left the squadroom, and Detective 3rd/Grade Alice Bannion sat down to type her report. She tried to do so unemotionally, with a minimum of involvement. But her spelling became more and more uncontrolled as she typed her way deeper into the report and the past. When she pulled the report out of the typewriter, she was sweating. She wished she hadn’t worn a girdle that day. She carried the typewritten pages into the lieutenant’s office, where Carella was waiting. She stood by the desk while Carella read what she had written.

“That’s it, huh?” he asked.

“That’s it,” she said. “Do me a favor next time, will you?”

“What’s that?”

“Ask your own questions,” Alice Bannion said, and she left the office.

“Let me see it,” Lieutenant Byrnes said, and Carella handed him the report:

DETAILS

Mrs. Redfield highly disturbed, did not wish to discuss matter at all. Claimed she had only told this to one other person in her life, her family doctor, and that because of urgency of matter, and need to do something about it. Has retained doctor over the years, general practitioner, Dr. Andrew Fidio, 106 Ainsley Avenue, Isola.

Mrs. Redfield claims drinks were forced upon her against will night of party Randolph Norden’s home, circa April 1940. Claims she was intoxicated when other students left at one or two in morning. Knew party was getting wild, but was too dizzy to leave. She refused to take part in what she knew was happening in other rooms, staying in living room near piano. Other two girls, Blanche Lettiger and Helen Struthers, forced Mrs. Redfield into bedroom, held her with assistance of boys while Randy Norden “abused” her. She tried to get out of room, but they tied her hands and one by one attacked her until she lost consciousness. She says all the boys participated in attack, and she can remember girls laughing. She seems to recall something about a fire, one of drapes burning, but memry is hazy. Someone took her home at about five a.m., she does not remember who. She did not report incident to sole living parent, mother, out of fear.

In circa October 1940, she went to Dr. Fidio with what seemed routine irritation of cervix. Blood test showed she was venereally infects, and that gonorrhea had entered chronic stage with internal scarring of female organs. She told Dr. Fidio about party in April, he suggested prosecution. She refused, not wanting mother to know about incident. But severity of symptoms indicated hysterectomy to Fidio, and she was admitted hospital in November, when he performed operation. Mother was told operation was appendectomy.

Mrs. Redfield feels to this day Randy Norden was boy who “diseased” her, but does not kniw for sure because each boy was attacker in turn. She stronly implies unnatural rlations with girls as well, but will not bring self to discuss it. She saed she was glad the boys were dead. When told that Blanche Lettiger had later became a prostitute, she said, “I’m not surprised.” She ended interview by saying, “I wish Helen was dead, too. She started it all.”

They worked on David Arthur Cohen for four hours, putting him through a sort of crash therapy his analyst would never have dreamed of. They had him tell and retell the details of that party long ago, read him sections of the report on Margaret Redfield, reread it, asked him to tell what had happened in his own words, asked him to explain the drapes being on fire, asked him what the girls had done, went over it and over it until, weeping, he could bear it no longer and simply repeated again and again, “I’m not a murderer, I’m not a murderer.”

The assistant district attorney, who had been sent up from downtown, had a small conference with the detectives when they were finished with Cohen.

“I don’t think we can hold him,” the assistant DA said. “We’ve got nothing that’ll stick.”

Carella and Meyer nodded.

“We’ll put a tail on him,” Carella said. “Thanks for coming up.”

They released David Arthur Cohen at 4:00 that afternoon. The detective assigned to his surveillance was Bert Kling. He never got to do any work, because Cohen was shot dead as he came down the precinct steps into the afternoon sunshine.

There were no buildings across the street from the station house: there was only a park. And there were no trees behind the low stone wall that bordered the sidewalk. They found a discharged shell behind the wall, and they assumed that the killer had fired from there, at a much closer range than usual, blowing away half of Cohen’s head. Kling had immediately run out of the muster room, and down the precinct steps, and across the street into the park, chasing aimlessly along paths and into bushes, but the killer was gone. There was only the sound of the whirling carousel in the distance.

Читать дальше