“We’re going on that assumption, Mr. Di Pasquale.”

“So where does that leave me? Do I get police protection?”

“If you want it.”

“I want it.”

“You’ll get it.”

“Pssssss,” Di Pasquale said.

“There’s just one other thing, Mr. Di Pasquale,” Kling said.

“Yeah, I know. Don’t leave town.”

Kling smiled. “That’s just what I was going to say.”

“Sure, what else could you say? I’ve been in this movie business a long time, kid. I’ve read them all, I’ve seen them all. It don’t take too much brains to figure it.”

“To figure what?”

“That if somebody’s out to get all of us who were in the play, well, kid, figure it. The somebody who’s out to get us could be somebody who was in the play, too. Right? So, okay, I won’t leave town. When are you sending the protection?”

“I’ll get a patrolman here within the half-hour. I should tell you, Mr. Di Pasquale, that so far the killer has struck without warning and from a distance. I’m not sure what good our protection will…”

“Anything’s better than nothing,” Di Pasquale said. “Look, baby, you finished with me?”

“Yes, I think…”

“Well, then, good, kid,” he said, leading him to the door. “If you don’t mind, I’m in a hell of a hurry. That guy’s gonna call me back at the office, baby, and I’ve got a million things on my desk, so thanks for coming up and talking to me, huh? I’ll be looking for the cop, kid, send him over right away before I’m gone, huh, baby? Good, it was nice seeing you, take it easy, baby, so long, huh?”

And the door closed behind Kling.

David Arthur Cohen was a sour little man who made his living being funny.

He operated out of a one-room office on the fourteenth floor of a building on Jefferson, and it was in this office that he greeted the detectives sourly, offered them chairs sourly, and then said, “It’s about these killings, isn’t it?”

“That’s right, Mr. Cohen,” Meyer said.

Cohen nodded. He was a thin man with a pained and suffering look in his brown eyes. He was almost as bald as Meyer, and the two men, sitting on opposite sides of the desk, with Carella standing between them at one end of the desk, looked like a pair of billiard balls waiting for a careful shooter to decide how he would bank them.

“It dawned on me when Mulligan was murdered,” Cohen said. “I’d recognized the other names before then, but when Mulligan got killed, the whole thing suddenly fell into place. I realized he was after all of us.”

“You realized this when Mulligan was killed, huh?” Meyer said.

“That’s right.”

“Mulligan was killed on May second, Mr. Cohen. This is May eighth.”

“That’s right.”

“That’s almost a full week, Mr. Cohen.”

“I know that.”

“Why didn’t you call the police?”

“What for?”

“To tell us what you suspected.”

“I’m a busy man.”

“We understand that,” Carella said. “But surely you’re not too busy to bother trying to save your own life, are you?”

“Nobody’s going to shoot me,” Cohen said.

“No. You have a guarantee of that?”

“Did you guys come up here to argue? I’m too busy to argue.”

“Why didn’t you call us, Mr. Cohen?”

“I told you. I’m busy.”

“What do you do, Mr. Cohen? What makes you so busy?”

“I’m a gag writer.”

“What do you mean?”

“I write gags.”

“For what? For whom?”

“For cartoonists.”

“Comic strips?”

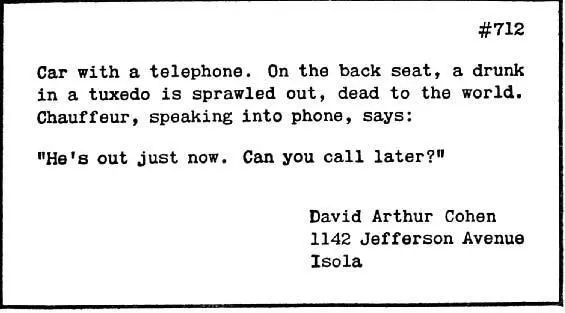

“No, no, single-box stuff. Like you see in the magazines. I write captions for them.”

“Let me get this straight, Mr. Cohen,” Carella said. “You work with a cartoonist who…”

“I work with a lot of cartoonists.”

“All right, you work with a lot of cartoonists who send you drawings to which you write captions? Is that it?”

“No. I send them the caption, and they make the drawing.”

“From the caption?”

“From a lot more than the caption.”

“I still don’t understand.”

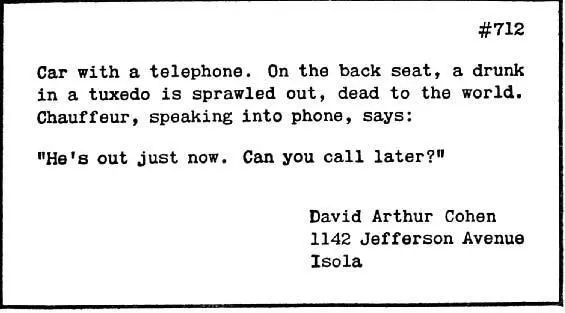

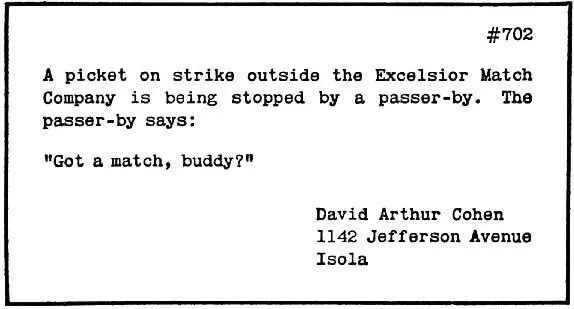

“Do you see these filing cabinets?” Cohen asked, waving his arm toward the wall behind him. “They’re full of cartoon ideas. I write up the gag, and then I send a batch of them to any one of the cartoonists on my list. They read the gags. If they like four, or five, or even one, they’ll hold it and draw up a rough sketch to show the humor editor of the magazine or newspaper. If the editor okays it, the cartoonist draws up a finish, gets his check, and sends me my cut.”

“How much is your cut?”

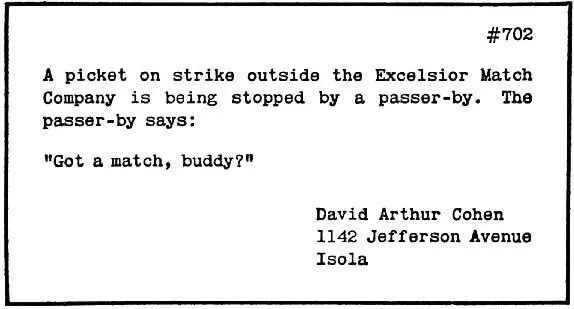

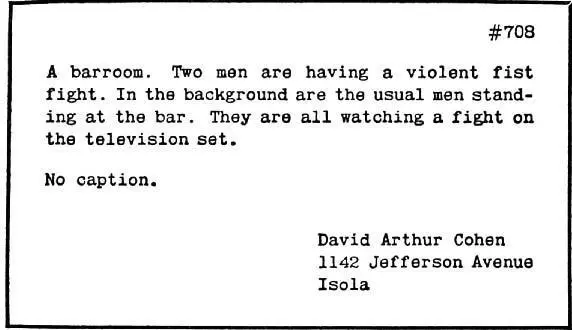

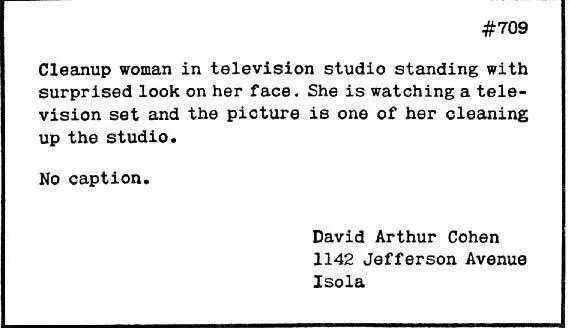

“I get ten percent of the purchase price.” Cohen looked at the detectives, saw that they were still puzzled, and said, “Here, let me show you.” He turned in his swivel chair, opened one of the files at random, and pulled out a thick sheaf of small white slips measuring about three by five. “There’s a gag typed on each one of these slips,” Cohen said. “See? That’s the number in the right-hand corner—each gag has a different number—and my name on the bottom of the slip.” He spread several of the slips on the desktop. Meyer and Carella leaned over the desk and read the nearest one.

“That’s what you send the cartoonist?” Carella asked.

“Yeah,” Cohen said. “Here’s a good one. Look at this one.”

Carella looked.

“That’s pretty funny,” Meyer said.

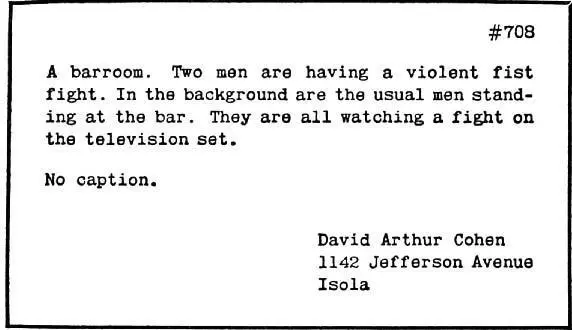

Cohen nodded sourly. “Here’s the one right after it. This is called snowballing. You write one gag, and another one along similar lines suggests itself, and you write that one. Here, look at it.”

“I don’t get it,” Meyer said.

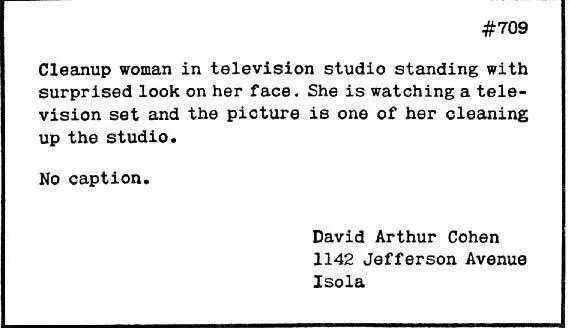

“Well, you either get them or you don’t,” Cohen answered, shrugging. “Here’s one of my favorites.”

“Is this what you do all day long?” Carella asked.

“All day long,” Cohen said.

“How many of these do you write every day?”

“It depends on how it’s going,” Cohen answered. “Sometimes I can turn out twenty or thirty a day. Other times I’ll just sit at the typewriter, and nothing’ll come to mind at all. It runs in cycles.”

“Do all cartoonists use gag writers?”

“Not all of them. But a great many. I send to about a dozen of them regularly. I’ve got…oh…maybe two hundred gags at market right this minute. I mean, gags they’ve held and drawn up to show around. I make a pretty good living at it.”

“I’d go out of my mind,” Meyer said.

“Well, it’s not bad, really it isn’t,” Cohen said.

“Do you enjoy doing it?” Carella asked.

For a moment the three men had forgotten why they were in that office. They were in that office to discuss six murders, but for the moment Cohen was a professional explaining his craft, and Meyer and Carella were two quite different professionals who were fascinated by the details of another man’s work.

“Sometimes it gets a little dull,” Cohen said. “When the ideas aren’t coming. But I usually enjoy it, yes.”

“Do your jokes make you laugh?” Carella asked.

Читать дальше