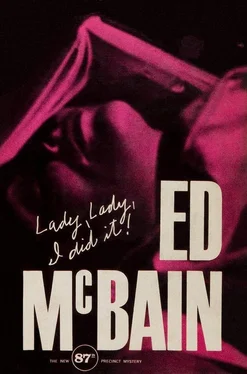

“Chills, febrile temperature, vomiting maybe, syncope, weakness, and eventually stupor and delirium.”

“I see,” Carella said.

“The autopsy revealed a slightly distended cervix, tenderness of the lower abdomen, discharge from the external os, and tenacula marks.”

“I see,” Carella said, not seeing at all.

“A septic infection,” Blaney stated simply. “And, at first, I thought it might have been the cause of death. But it wasn’t. Although it certainly ties in with what did kill her.”

“And what was that?” Carella asked patiently.

“The bleeding.”

“But you said there were no wounds.”

“I said there were no visible wounds. Of course, the tenacula marks were a clue.”

“What are tenacula marks?” Carella asked.

“Tenacula is a plural for tenaculum — Latin,” Blaney said. “A tenaculum is a surgical tool, a small sharp-pointed hook set in a handle. We use it for seizing and picking up parts. Of the body, naturally. In operations or dissections.”

Carella suddenly remembered that he didn’t very often like talking to Blaney. He tried to speed the conversation along, wanting to get at the facts without all the details.

“Well, where were these tenacula marks?” he asked pointedly.

“On the cervical lip,” Blaney said. “The girl had bled profusely from the uterine canal. I also found pieces of pla—”

“What did she die from, Blaney?” Carella asked impatiently.

“I was getting to that. I was just telling you. I found pieces of pla—”

“How did she die?”

“She died of uterine hemorrhage. The septicemia was a complication.”

“I don’t understand. What caused the hemorrhage?”

“I was trying to tell you, Carella, that I also found pieces of placental tissue in the cervix of the uterus.”

“Placental...?”

“The way I figure it, the job was done either Saturday or Sunday sometime. The girl was probably wandering around when—”

“What job? What are you talking about, Blaney?”

“The abortion,” Blaney said flatly. “That little girl had an abortion sometime over the weekend. You want to know what killed her? That’s what killed her!”

Somebody had to tell Kling what everybody in the squadroom decided that Tuesday. Somebody had to tell him, but Kling was at a funeral. So, instead of speculating, instead of hurling theories at a man who was carrying grief inside him, instead of telling him that one of those closets they’d spoken about had finally been opened and, like all closets opened in the investigation of a homicide, it contained something that should have remained hidden — instead of confronting him with something they knew he would disbelieve anyway — they decided to find out a little more about it. Carella and Meyer went back to see the girl’s mother, Mrs. Glennon, leaving Bert Kling undisturbed at the funeral.

Indian summer was out of place at that cemetery.

Oh, she had charm, that guileful bitch. The trees lining the road to the burial plot were dressed in gaudy brilliance, reds and oranges and burnt yellows and browns and unimaginable hues mixed on a Renaissance palette. Hotly, they danced overhead, whispering secrets to the balmy October breeze, while the mourners marched beneath the branches of the trees, following the coffin in colorless black, their heads bent, their feet drifting through idle fallen leaves, whispering, whispering.

The hole in the earth was like an open wound.

The grass seemed to end abruptly, and the freshly turned earth began in moist rich darkness, its virgin aroma carried on the air. The grave was long and deep. The coffin was suspended over it, held aloft on canvas straps attached to the mechanism that would lower it gently into the earth.

The sky was so blue.

They stood like uneasy shadows against the wide expanse of sky and the gaudy exhibitionism of the autumn trees. They stood with their heads bent. The coffin was poised for disappearance.

He looked at the black shining box and beyond that to where a man was waiting to release the mechanism. Everything seemed to shimmer in that moment because his eyes had suddenly filled with tears. A hand touched his arm. He turned, and through the glaze of tears he saw Claire’s father, Ralph Townsend. The grip tightened on his arm. He nodded and tried to hear the minister’s words.

“...above all,” the minister was saying, “she goes to God even as she was delivered from Him: pure of heart, clean of spirit, honest and unafraid of His infinite mercy. Claire Townsend, may you rest in eternal peace.”

“Amen,” they said.

Mrs. Glennon had had it. She had had it up to here. She didn’t want to see another cop as long as she lived. She had identified her daughter at the morgue before they had begun autopsy and then had gone home to put on her widow’s weeds, the same black clothing she had worn years ago when her husband had died. And now there were cops again — Steve Carella and Meyer Meyer. Meyer, in true private eye fashion, had swum up out of that pool of blackness, had had his cuts and bruises dressed, and now sat wearing a serious look and a great deal of adhesive plaster. Mrs. Glennon faced them in stony silence while they fired questions at her, refusing to answer, her hands clenched in her lap as she sat unflinchingly in a hard backed kitchen chair.

“Your daughter had an abortion, do you know that, Mrs. Glennon?”

Silence.

“Who did it, Mrs. Glennon?”

Silence.

“Whoever did it killed her, do you know that?”

Silence.

“Why didn’t she come back here?”

“Why’d she wander the streets instead?”

“Was the abortionist in Majesta? Is that why she was there?”

“Did you kick her out when you learned she was pregnant?”

Silence.

“Okay, Mrs. Glennon, let’s take it from the top. Did you know she was pregnant?”

Silence.

“How long was she pregnant?”

Silence.

“Goddamn it, your daughter is dead, do you know that?”

“I know that,” Mrs. Glennon said.

“Did you know where she was going Saturday when she left here?”

Silence.

“Did you know she was going to have an abortion?”

Silence.

“Mrs. Glennon,” Carella said, “we’re just going to assume you did know. We’re going to assume you had foreknowledge that your daughter was about to produce her own miscarriage, and we’re going to book you as an accessory before the fact. You better get your coat and hat.”

“She couldn’t have the baby,” Mrs. Glennon said.

“Why not?”

Silence.

“Okay, get your things. We’re going to the station house.”

“I’m not a criminal,” Mrs. Glennon said.

“Maybe not,” Carella answered. “But induced abortion is a crime. Do you know how many young girls die from criminal operations in this city every year? Well, this year your daughter is one of them.”

“I’m not a criminal.”

“Abortionists get one to four years, Mrs. Glennon. The woman who submits to an abortion can get the same prison term. Unless either she or her ‘quick’ child dies. Then the crime is firstdegree manslaughter. And even a relative or friend who guided the woman to an abortionist is held guilty of being a party to the crime if it can be shown that the purpose of the visit was known. In other words, an accessory is as guilty as any of the principals. Now how do you feel about that, Mrs. Glennon?”

“I didn’t take her anywhere. I was here in bed all day Saturday.”

“Then who took her, Mrs. Glennon?”

Silence.

“Did Claire Townsend?”

“No. Eileen went alone. Claire had nothing to do with any of this.”

Читать дальше

![Дэвид Лоуренс - Lady Chatterley's Lover [С англо-русским словарем]](/books/26613/devid-lourens-lady-chatterley-s-lover-s-anglo-thumb.webp)