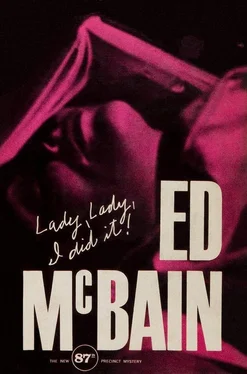

“You have a daughter, Mrs. Glennon?”

“And a son. Why?”

“How old are the children?”

“Eileen is sixteen and Terry is eighteen. Why?”

“Where are they now, Mrs. Glennon?”

“What’s it to you? They haven’t done anything wrong.”

“I didn’t say they had, Mrs. Glennon. I simply—”

“Then why do you want to know where they are?”

“Actually, we’re trying to locate—”

“I’m here, Mom,” a voice behind Meyer said. The voice came suddenly, startling him. His hand automatically went for the service revolver clipped to his belt on the left — and then stopped. He turned slowly. The boy standing behind him was undoubtedly Terry Glennon, a strapping youth of eighteen, with his mother’s piercing eyes and narrow jaw.

“What do you want, mister?” he said.

“I’m a cop,” Meyer told him before he got any wild ideas. “I want to ask your mother a few questions.”

“My mother just got out of the hospital. She can’t answer no questions,” Terry said.

“It’s all right, son,” Mrs. Glennon said.

“You let me handle this, Mom. You better go, mister.”

“Well, I’d like to ask—”

“I think you better go,” Terry said.

“I’m sorry, sonny,” Meyer said, “but I happen to be investigating a homicide, and I think I’ll stay.”

“A homi...” Terry Glennon swallowed the information silently. “Who got killed?”

“Why? Who do you think got killed?”

“I don’t know.”

“Then why’d you ask?”

“I don’t know. You said a homicide, so I naturally asked—”

“Uh-huh,” Meyer said. “You know anyone named Claire Townsend?”

“No.”

“I know her,” Mrs. Glennon said. “Did she send you here?”

“Look, mister,” Terry interrupted, apparently making up his mind once and for all, “I told you my mother’s sick. I don’t care what you’re investigating — she ain’t gonna—”

“Terry, now stop it,” his mother said. “Did you buy the milk I asked you to?”

“Yeah.”

“Where is it?”

“I put it on the table.”

“Well, what good is it gonna do me on the table, where I can’t get at it? Put some in a pot and turn up the gas. Then you can go.”

“What do you mean, go?”

“Downstairs. With your friends.”

“What do you mean, my friends? Why do you always say it that way?”

“Terry, do what I tell you.”

“You gonna let this guy tire you out?”

“I’m not tired.”

“You’re sick!” Terry shouted. “You just had an operation, for Christ’s sake!”

“Terry, don’t swear in my house,” Mrs. Glennon said, apparently forgetting that she had profaned Christ’s mother earlier, when Meyer was standing in the hallway. “Now go put the milk up to heat and go downstairs and find something to do.”

“Boy, I don’t understand you,” Terry said. He shot a petulant glare at his mother, some of it spilling onto Meyer, and then walked angrily out of the room. He picked up the container of milk from the table, went into the kitchen, banged around a lot of pots, and then stormed out of the apartment.

“He’s got a temper,” Mrs. Glennon said.

“Mmmmm,” Meyer commented.

“Did Claire send you here?”

“No, ma’am. Claire Townsend is dead.”

“What? What are you saying?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Tch,” Mrs. Glennon said. She tilted her head to one side and then repeated the sound again. “Tch.”

“Were you very friendly with her, Mrs. Glennon?” Meyer asked.

“Yes.” Her eyes seemed to have gone blank. She was thinking of something, but Meyer didn’t know what. He had seen this look a great many times before, a statement triggering off a memory or an association, the person being interrogated simply drifting off into a private thought. “Yes, Claire was a nice girl,” Mrs. Glennon said, but her mind was on something else, and Meyer would have given his eyeteeth to have known what.

“She worked with you at the hospital, isn’t that right?”

“Yes,” Mrs. Glennon said.

“And with your daughter, too.”

“What?”

“Your daughter. I understand Claire was friendly with her.”

“Who told you that?”

“The intern at Buenavista.”

“Oh,” Mrs. Glennon nodded. “Yes, they were friendly,” she admitted.

“Very friendly?”

“Yes. Yes, I suppose so.”

“What is it, Mrs. Glennon?”

“Huh? What?”

“What are you thinking about?”

“Nothing. I’m answering your questions. When... when did... When was Claire killed?”

“Friday evening,” Meyer said.

“Oh, then she—” Mrs. Glennon closed her mouth.

“Then she what?” Meyer asked.

“Then she... she was killed Friday evening,” Mrs. Glennon said.

“Yes.” Meyer watched her face carefully. “When was the last time you saw her, Mrs. Glennon?”

“At the hospital.”

“And your daughter?”

“Eileen? I... I don’t know when she saw Claire last.”

“Where is she now, Mrs. Glennon? At school?”

“No. No, she... she’s spending a few... uh... days with my sister. In Bethtown.”

“Doesn’t she go to school, Mrs. Glennon?”

“Yes, certainly she does. But I had the appendicitis, you know, and... uh... she stayed with my sister while I was in the hospital... and... uh... I thought I ought to send her there for a while now, until I can get on my feet. You see?”

“I see. What’s your sister’s name, Mrs. Glennon?”

“Iris.”

“Yes. Iris what?”

“Iris — why do you want to know?”

“Oh, just for the record,” Meyer said. “I don’t want you to bother her, mister. She’s got troubles enough of her own. She doesn’t even know Claire. I wish you wouldn’t bother her.”

“I don’t intend to, Mrs. Glennon.”

Mrs. Glennon frowned. “Her name is Iris Mulhare.”

Meyer jotted the name into his pad. “And the address?”

“Look, you said—”

“For the record, Mrs. Glennon.”

“1131 56th Street.”

“In Bethtown?”

“Yes.”

“Thank you. And you say your daughter Eileen is with her, is that right?”

“Yes.”

“When did she go there, Mrs. Glennon?”

“Saturday. Saturday morning.”

“And she was there earlier, too, is that right? While you were in the hospital.”

“Yes.”

“Where did she meet Claire, Mrs. Glennon?”

“At the hospital. She came to visit me one day while Claire was there. That’s where they met.”

“Uh-huh,” Meyer said. “And did Claire visit her at your sister’s home? In Bethtown?”

“What?”

“I said I suppose Claire visited her at your sister’s home.”

“Yes, I... I suppose so.”

“Uh-huh,” Meyer said. “Well, that’s very interesting, Mrs. Glennon, and I thank you. Tell me, haven’t you seen a newspaper?”

“No, I haven’t.”

“Then you didn’t know Claire was dead until I told you, is that right?” “That’s right.”

“Do you suppose Eileen knows?”

“I... I don’t know.”

“Well, did she mention anything about it Saturday morning? Before she left for your sister’s?”

“No.”

“Were you listening to the radio?”

“No.”

“Because it was on the air, you know. Saturday morning.”

“We weren’t listening to the radio.”

“I see. And your daughter didn’t see a newspaper before she left the house?”

“No.”

“But, of course, she must know about it by now. Has she said anything about it to you?”

“No.”

“You’ve spoken to her, haven’t you? I mean, she does call you. From your sister’s?”

Читать дальше

![Дэвид Лоуренс - Lady Chatterley's Lover [С англо-русским словарем]](/books/26613/devid-lourens-lady-chatterley-s-lover-s-anglo-thumb.webp)